For a work that ponders the vast, infinite reaches of space and what might lie beyond, Starfield doesn’t provide many opportunities to stop and just take it all in.

With an impressively ambitious scope, Starfield is a playset that encapsulates our entire known universe and several more beyond it, stuffed with innumerable concepts, stories, characters, and possibilities. Much of it is compelling.

But the quiet, humbling awe that comes from seeing and exploring the vast unknown – which Starfield clearly tries to evoke with its broad overall tone, vivid aesthetic, richly detailed worlds, and its tale of eager explorers – is so often drowned out by an unending stream of over-attentive noise and chatter urging you in all directions, and punctuated by humdrum, menu-based tasks. Starfield’s ideas provide a fantastic spark of inspiration – a big bang, even – but your own enthusiasm and imagination are ultimately needed to realise the full picture.

Travelling at Light Speed

Cast as a lowly space miner who has an unfathomable experience when touching an object of mysterious origin, Starfield immediately thrusts you into a spacefaring adventure in a far-flung future, where humanity has long since discovered lightspeed travel, abandoned Earth, and settled across several colonies, across several planets, across several star systems. Inducted into an explorer’s group called Constellation, you’re tasked with tracking down more of these mysterious objects – and encouraged to get sidetracked by the rest of the universe along the way.

You’ll quickly become entangled within storylines that involve different factions, corporations, religions, military organisations, pirates, and smaller trifles with the inhabitants of the several planets you visit. Depending on the decisions you make, you might undertake a deep undercover operation within a criminal organisation, maintain law and order as a space cowboy, participate in corporate espionage, become a drug smuggler, space trucker, make friends and lose them, live, laugh, and love.

It’s an overwhelming prospect at first, and much of your induction into Starfield will involve trying to get your bearings, and understanding how to navigate the dense web of interiors, cities, planets, and star systems via interstellar travel.

The answer is less overwhelming: Lots of menus, maps, and instantaneous fast-travel.

In contrast to spacefaring games like No Man’s Sky and Outer Wilds, Starfield dramatically condenses much of the actual journey associated with space travel into something much closer to Destiny, where you simply select a destination and are instantly whisked away.

Pieces of the voyaging fantasy are present – while planetside, you can enter your spaceship, walk around it, sit down in the pilot’s chair, and choose to go into orbit. But from there, you’re instantly teleported to a pre-designated, enclosed pocket of space above the same planet, which is used for encounters with friendly ships, dogfights with hostile ones, or potentially nothing at all.

To travel, you open up your map menu to pick a system, and a planet. Once confirmed, you’ll whisk away to that planet’s respective orbital pocket. To land, you’ll open up your map screen once more, select a designated landing zone on the planet, confirm the location, and transition to the ground. In many circumstances, you can skip much of the legwork, and simply select another distant city to transition to.

The intention seems to be making sure you’re never too far from your next mission objective or an opportunity where you can stumble across something to do – dogfights, random encounters, and scans for contraband often occur the instant you arrive in a new orbital pocket.

But this interpretation of space travel also has the effect of diminishing the enormous scope of Starfield‘s setting, creating a weaker sense of place. With instant transitions between planets becoming the default and nothing but an abstract map to try and portray the enormous distances travelled, the universe feels surprisingly small. Your ship rarely feels like a transport, because you’re never given the opportunity to be active on it while it’s going anywhere.

With each planet being largely defined by a single city or point of interest, it makes places that are literally worlds apart seem like they’re right across the street from one another. Despite the game’s themes and quests about exploring the unknown, you always know exactly where you’re going in Starfield. It’s marked right there on your map, ready for you to instantly fast-travel.

Additionally, given the starfaring nature of many of Starfield’s quests, this method of travel means you’ll find yourself buried in maps and menus for a remarkable amount of time, hopping from pocket to pocket, especially as you travel to further reaches later in the game. And that’s not to mention the amount of time you’ll also spend in long, scrolling text-based menus managing your inventory and ship cargo.

Eventually, you do come to appreciate the brisk flow, especially in quests where a lot of back-and-forth travel is required. But with no option to enjoy the journey, the downtime of travel, the feeling of getting lost in space, that part of Starfield’s fantasy has to blossom in your own mind – like mentally filling in the gaps between comic book panels.

And for a game about exploring beyond the boundaries, Starfield feels strangely content to guide you through known spaces. That’s perfectly fine a lot of the time – the quests are compelling because of the stories they tell, the curated environments, and the choices on offer that shape your experience – very much in line with previous Bethesda Game Studios titles like Skyrim and Fallout 4. But what Starfield sadly lacks is the joyful illusion of self-exploration and discovery that made the aforementioned titles so magical – the constant jumps to defined spaces make it feel like everything is delivered to you on a platter.

Land on a minor planet, and you’ll have two to three clear points of interest on the surface, with little of note other than resources to harvest (for when your attention eventually falls to base-building and crafting) on your long walk toward them. And while entering the orbit of a planet and immediately being hailed by a very loose party cruise is entertaining, those random events rarely feel organic. That feeling of stumbling upon a lost individual in the world, or coming across a poignant little diorama of props that tells a wordless story, is seemingly absent in Starfield.

Beneath the Starfield

All of that unused potential has apparently gone into the game’s cities and countless other interior environments instead. Packed densely with people and objects, these are the places you get lost in.

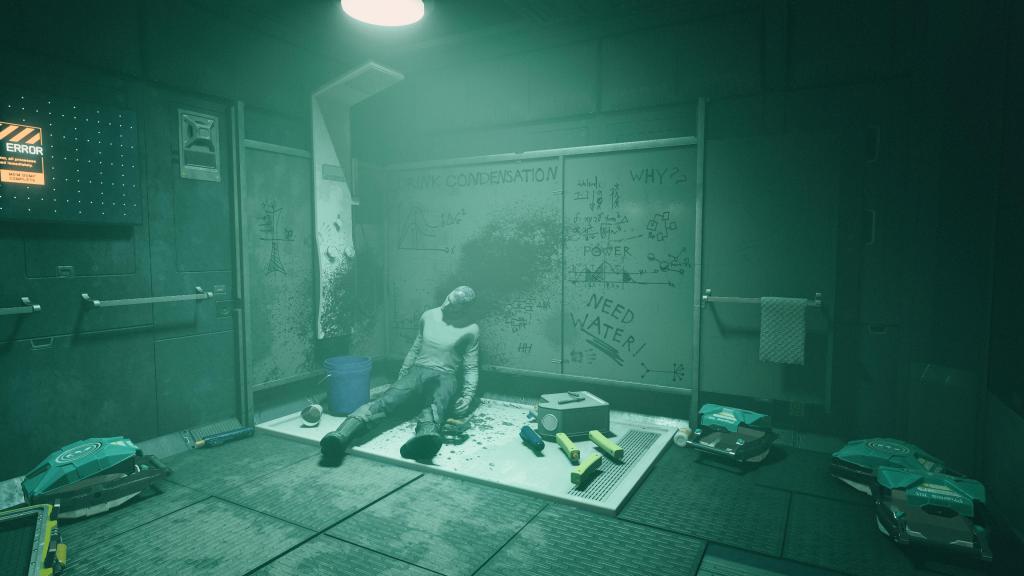

Starfield’s best moments are those that push you to explore enclosed, hand-crafted locations and appreciate the meticulous work that has gone into the level dressing and design. From abandoned research stations, to an intergalactic cruise ship, to maximum security prisons, mundane offices, space stations, homesteads, and pirate dens. Every place feels lived in, making you want to pore over every surface, examine every computer, and pick every lock to uncover more details, piecing together the story behind it.

Each major hub location is distinctly themed enough to be memorably different, playing into a different brand of familiar sci-fi trope, and filled with quests to go along with it, too. There’s the immaculately clean high-tech society of New Atlantis, the rainy cyberpunk-infused streets of Neon, and the frontier space-western-themed Akila City, among others.

The fact that you find yourself flitting between these disparate locations, pursuing quests of varying styles and tones often makes Starfield feel like a long-running anthology series rather than one long, epic space saga. When one story ends, you’ll put the game down, and likely find yourself somewhere completely different the next time, wondering what flavour of tale awaits.

It’s hard to overstate just how many adventures there are too, with most offering varying ways to resolve them. At the time of writing, after completing the primary Constellation questline, a number of multi-part, faction-specific stories, and a few dozen miscellaneous tales, there are still dozens upon dozens of quests and activities backlogged in my playthrough. Many of the major questlines have multiple tantalising branching paths to go down, with clear forks in the road that shape your character and the particular universe they inhabit, making you wonder about the roads not taken.

What Starfield has trouble with here, however, is completely nailing the human element of these quests and selling real, emotional stakes. Outside of major quests, whose plot points and twists are inherently dramatic in the grand narrative of Starfield, the effectiveness of the more personal facets in these stories can feel inconsistent.

Starfield adopts the familiar ‘singular talking head’ approach to character conversation traditionally adopted by Bethesda Game Studios titles. But the technique and its associated quirks feel distinctly old-fashioned in Starfield, especially when the rest of the game is so impressively evocative.

The sheer number of individuals in Starfield means that character models vary greatly in terms of quality, but stilted bodies, little in the way of physical expressions, and cold uncanny eyes are an eerie constant. The burden of invoking humanity lies solely on the vocal performances of Starfield’s actors, who offer yet another starting spark to help you to build out your own mental impression of characters – which you then reproject onto the game itself.

The performances are mostly strong, with some of the most exceptional examples thankfully lying with your companions, the characters you’ll likely be spending the most time with. Particular highlights include Cissy Jones as Andreja and Barry Wiggins as Barrett, whose vocal presences certainly transcend their character models.

But even then, Starfield’s penchant for overstimulation often undercuts some of the good work here. Companions and non-player characters are chatty to a fault, frequently dishing out contextual remarks and never letting a quiet moment linger for too long. Walk through a town, and you’ll almost be harassed with strangers barking at you. My personal experience of some of the biggest, emotional moments in the game – life-or-death tension, uncontrollable grief, solemn heartache – would frequently be undercut by an incognizant, generic upbeat quip from a companion I otherwise adored, sometimes immediately after they themselves delivered an emotional monologue. And no Sarah, I don’t have a moment to speak with you right now – can’t you see we’re literally in the midst of a firefight with pirates?

Bright Side of the Moon

These oddities and quirks (among many more), whether they exist by design, because of technical issues, as a result of sheer ambition, or something else entirely, feel particularly thorny because of what Starfield otherwise does so well to sell the fantasy.

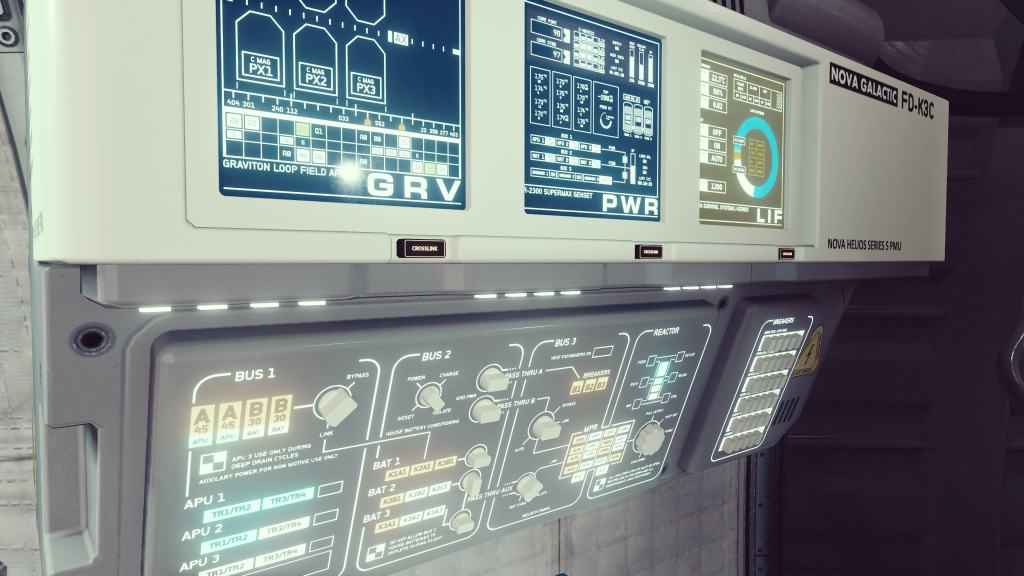

In terms of aesthetic design, Starfield is a marvel. The art direction, a retro-futuristic interpretation of the far future that’s obsessed with beige plastic, clacky mechanical buttons, keys and dials, is pure delight. The approach enhances the physicality of the imagined spaces and technology, with a desaturated palette and persistent film grain painting the world in a classical, cinematic look. Spaceship interiors are laced in meticulous, tactile detail. Digital user interfaces are monospaced and bitmapped, as if it never advanced past the 1980s. Despite the far-flung fantasy, these decisions make everything seem so real and believable.

And though the planet surfaces themselves may largely be sparse, landing and stepping out of your ship onto a new location often comes with an arresting moment that you wish you could bottle – the way the light falls on the topography, the way the night sky glimmers, the feeling of gazing out on a nearby planet – and it’s all elevated by a stirring soundtrack that invokes the slow, contemplative woodwinds of 70s sci-fi fantasies.

Gunplay and combat feel sharp and weighty, too. A tactical-style playthrough relying on stealth, melee attacks, and ballistic weapons provided great satisfaction throughout missions – especially with the game’s skill system, which demands that you perform certain actions to improve particular skills, and especially when major narrative events equip you with a dynamic new set of options to use.

Though limited to restricted orbital arenas, starfighting in your ship is straightforward, but pleasing – largely due to the evocative aesthetic treatment of your cockpit and the strong audio design. Constructing your own ship and planetary outposts later in the game are also enjoyable ventures – once you familiarise yourself with tools, they feel natural and flexible. Building out and decorating a base as you walk through it can feel magical.

It’s the static and mechanical elements of Starfield that shine the brightest – the art, the environments, the combat systems. They make up the strong foundations of a playset with a very intriguing scenario. But you need to mentally meet Starfield partway to complete its vision of a vast, living universe. You need to stretch out the expanse and envision the journey. You need to look past the menus and form the fantasy. You need to help breathe life into its paper dolls. You need to add your own dash of wonder, and imagine your own unknowns. Truly, Starfield is a role-playing game, through and through.

4 Stars: ★★★★

Starfield

Platforms: PC, Xbox Series X/S

Developer: Bethesda Game Studios

Publisher: Bethesda Softworks

Release Date: 6 September 2023 (1 September 2023 Early Access)

A copy of Starfield was provided and played on an Xbox Series X for the purposes of this review. GamesHub reviews are scored on a 5-point rating scale. GamesHub has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content. GamesHub may earn a small percentage of commission for products purchased via affiliate links.