It’s weird when a platformer asks you to slow down. In the traditional of Prince of Persia or Flashback, Lunark requests patience. A sci-fi mystery with a touch of mysticism, Lunark’s deliberate controls and exacting demands serve it well while you’re steadily uncovering its secrets. However, it runs into trouble on the rare occasions it expects you to hurry.

From Super Mario and Sonic the Hedgehog onwards, the platformer urges forward motion, a kind of justified faith in the belief that glory – or at least the end of the level – awaits if you just keep running from left to right. This principle reached its logical conclusion with the release of Canabalt in 2009, and subsequent popular resurgence of the endless runner.

But the cinematic platformer has always moved at its own pace.

A sort of micro-genre at best, the cinematic platfomer emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s through efforts both to portray the action of a platformer – the running, the jumping, the fighting or shooting –with greater realism, and to chart the character’s progress across a deeper, more sophisticated story arc.

For Prince of Persia in 1989, Jordan Mechner filmed his brother running, jumping and climbing up ledges, then traced over the footage to create frames of animation for the titular Prince. For Another World in 1991, Eric Chahi deployed the same rotoscoped animation alongside filmic story-telling techniques, such as close-ups and cutaways. Despite the fantasy and sci-fi settings, the focus elsewhere on realism resulted in playable characters who moved like a real person, could only jump as high as a real person, and would die like a real person if they fell from a certain height.

In subsequent decades, the handful of cinematic platformers, as the genre has come to be known, that followed Prince of Persia and Another World have affirmed this same commitment to realism. In Flashback or Abe’s Oddysee or Limbo or Deadlight, animation takes priority. When you press a button to perform an action, you commit to letting the animation play out. You’ve got to jump *before* the ledge, not as you reach it. There are no take-backs or cancels. You can’t change direction in mid-air. Lunark is similarly unwavering.

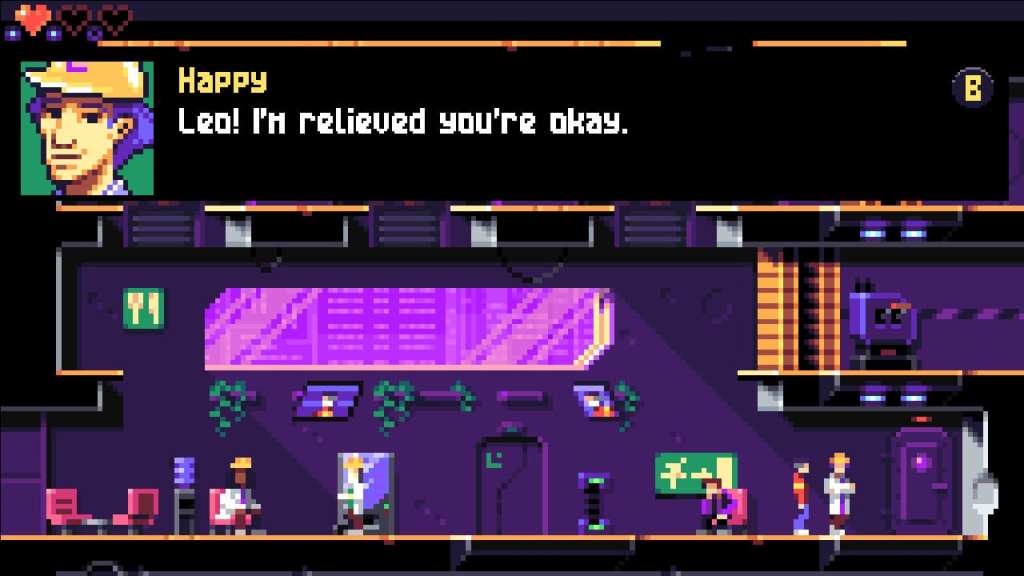

In Lunark, there’s a button to jump, which will send you leaping forward a set distance. You’ll press another button to grab a ledge, from which you’ll hang until you press another button to haul yourself up. Crouch or forward roll and you have to wait for those animations to conclude before you can draw your gun and shoot. To jump to the ledge above, you have to step to the exact right spot, then jump up, then grab, then pull yourself up. Everything takes time, or feels like it’s on a slight delay, a design philosophy that constantly thumbs its nose at the conventional wisdom of platform design that decrees responsiveness at any instant.

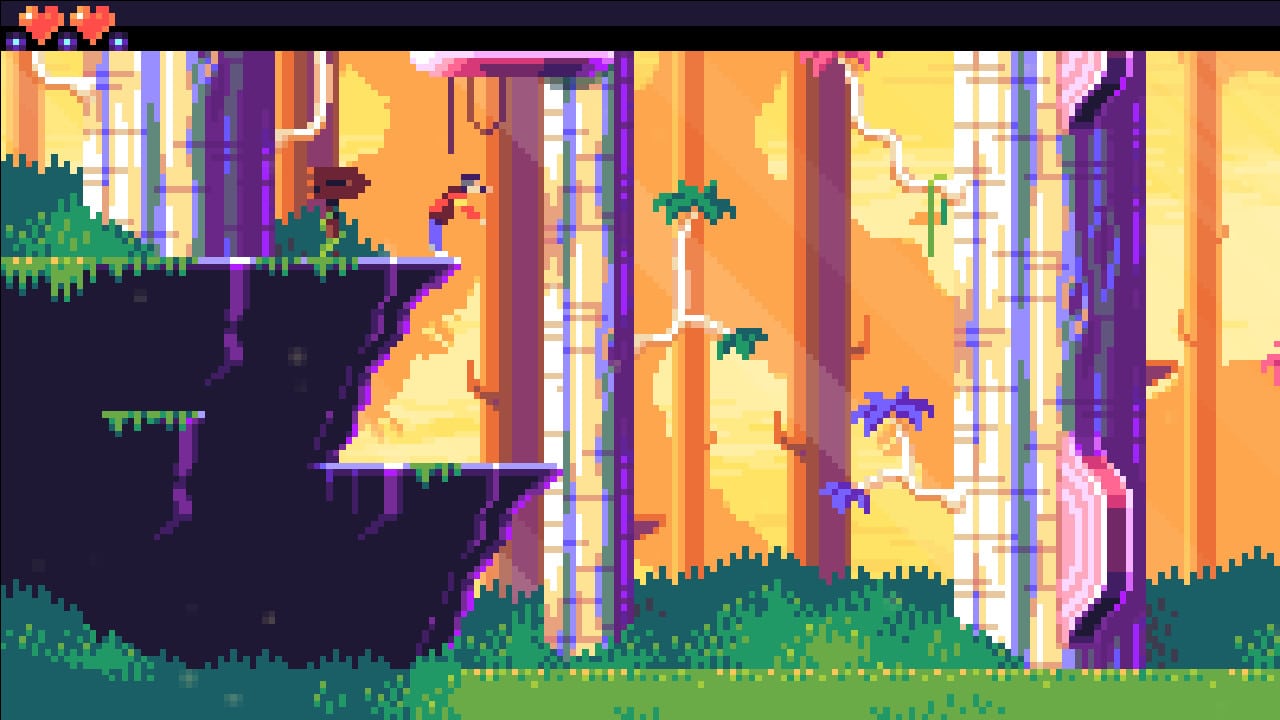

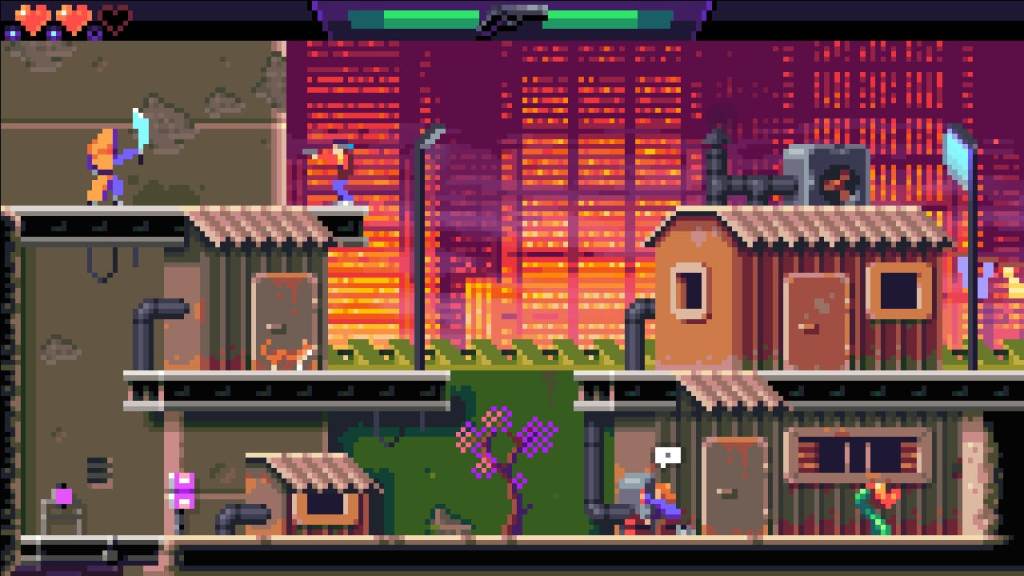

It sounds terrible. Why would anyone want to play a game where the controls aren’t intuitive? But when it works, it succeeds in situating you in your character’s shoes, in a way that a control and animation system with less friction would struggle to achieve. Lunark succeeds in enabling you to feel the contours of its platforms as you grapple with hauling yourself around them. Varied locations, from cyberpunk streets to alien jungles, feel like physical environments that in some tangible, tactile way you’re now inhabiting. As you come to learn how many steps you have to take to position yourself for the next jump, or when you’re learning the timing of a multi-screen gauntlet of security droids and jumps and rolls and explosions, the action becomes rhythmic in a manner that is fully realised by how measured each button press needs to be.

Of course, there are times when it doesn’t work so well. There are a couple of sections that feel like they ask just a bit too much, too quickly. Certain puzzle rooms on a strict timer, where one false move means repeating the entire process, are irritating. As is a checkpointing system that occasionally feels like it throws you back too far when you fail. And an autosave system that resets the whole chapter when you quit the game is infuriating. Pro tip: Don’t quit the game mid-chapter.

Lunark wears its inspirations on its sleeve. It is littered with subtle and blatant nods to Flashback, in particular. In an under-populated genre, the heavy weight of those influences are conspicuous. Yet, at the same time, it’s just pleasing to encounter another cinematic platformer that understands the appeal of the genre, and doesn’t try to fix what ain’t broke. Sometimes, slowing down is precisely what you need.

Four stars: ★★★★

LUNARK

Platforms: PC, Mac, Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 5, PlayStation 4, Xbox Series X/S

Developer: Canari Games

Publisher: WayForward

Release Date: 31 March 2023

The PC version of Lunark was provided and played for the purposes of this review. GamesHub has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content. GamesHub may earn a small percentage of commission for products purchased via affiliate links.