Art might be one of the most poorly defined concepts humans deal with. We’re always having a conversation about whether or not some new form of media is art, as we rub our chins and perpetuate dumb rhetoric like ‘well what is art anyway? Chicory: A Colourful Tale makes the case that art is a state of being, rather than a status to be earned. In fact, it’s desperate to prove this to you.

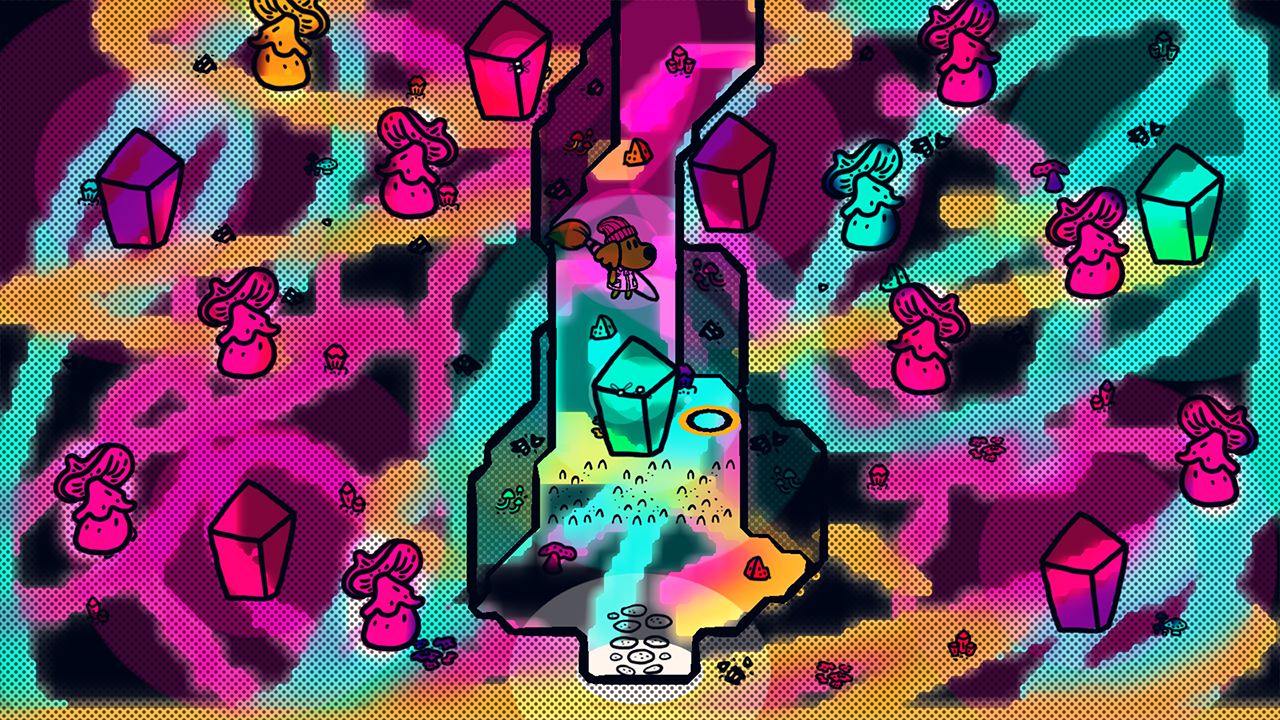

In the top-down 2D world of Chicory’s Picnic, everything is vibrantly coloured thanks to The Wielder, an artist who rises above the rest to be entrusted with a brush to colour and paint the world. Passed on through time, there have been many artists with different styles to hold The Brush, all of who worked to hone their craft and bring a touch of beauty. The current Wielder is Chicory, a long-eared hare with a penchant for beautiful vibrant colours, and it’s made clear the wielder is an honoured title with grand responsibilities.

You do not play The Wielder. Or even an artist. You are a dog, who is also a janitor, named after your favourite food (in my case, ‘Chocolate’).

While doing your duty cleaning, all he beautiful colour is drained from the world. It changes Picnic into a stark black and white environment, like an untouched colouring book. Chicory is nowhere to be found, but her brush, the brush, comes into your grubby little paws.

From there, you have the power to colour literally anything in the world. Houses, grass, trees, buildings, even the other animal residents. Some won’t be big fans, be it of your painting or the colours you use, while others will adore your work and will beg you to use The Brush. Alternate brush shapes, such as shape stamps or texture brushes made up of dots and lines are common rewards for side tasks and secret puzzles. They can help add some flair to your creations but are optional and limited. Story rewards are typically more practical, giving your brush new powers like glowing paint to illuminate caves, or the ability to swim through your masterpieces. Regardless of what it was for, every action you take with the brush is treated as art.

But it also looks like shit.

And so Chicory becomes a dilemma of a game that makes you ponder the idea of ‘what is art anyway?’ The artist in me wanted to make this world beautiful, and I just couldn’t. Using the brush in Chicory is like drawing in MS Paint with a mouse; you can also use a controller. You start out with limited brush shapes and each area will limit you to the use of only a few colours at a time. At one point I encountered a glitch where I couldn’t swap to a smaller brush size which made everything look and feel even worse to me. I was frustrated because I had already forgotten that I wasn’t supposed to be playing as an artist–just a silly dog with an even sillier name.

Painting has practical uses in Chicory, such as solving the game’s thought-provoking puzzles. Painting enough of the world can unlock new pathways, for example, many plants grow or shrink when coloured in, and more abilities unlock as your bond with the brush grows throughout the game. So even though I hated all my art, I still dragged my brush across the screen diligently, uncovering secrets and progressing the story. With this, Chicory pushed me through the motions of making art even when you hate it, a confronting feeling which is, I think, a pretty big part of being an artist.

The citizens of Picnic would sometimes compliment my work, which felt like a slap across the face. A t-shirt I designed for the local cafe found plenty of joyous wearers – after all, it was done by The Wielder and these characters had no sense of how bad it looked. Sometimes they’d come to an area I had previously painted to remark on its new beauty. I’d look at the screen and see a smear of one or two colours.

Being staggeringly aware of the fact that the compliments come from preprogrammed (if charmingly written) characters, made it impossible to actually accept. These interactions felt hollow a lot of the time, but then again, they reminded me of times when people complimented my art in real life.

All you’re really doing is standing in for the real artist and wielder, Chicory. It’s a bit easier to be Chocolate, to accept the compliments with a smile, because you know that you’re both just doing the best you can. If the characters really do like it, then maybe that’s ok. But it’s a kindness I can barely imagine even offering to myself.

There’s a special kind of internal pressure to creativity and self-expression, above and beyond the external pressure of the profession, that can be hard to explain. It can be incredibly difficult to be happy with a creation that’s born of your own mind. Nothing will ever look as good as the ideals in my head so everything, if only in a small way, will feel like a failure in some respect and it’s easy to become resentful towards the process. Even if I am, by some miracle, even slightly happy with what I create, it comes with a pang of guilt. Is it even acceptable for me to want other people to see the (sometimes deeply personal) things I’ve created, or is that just incredibly narcissistic?

There’s a desperation for worthiness, as though it’s possible to achieve. Like earning your pen license in school and suddenly being allowed to write in ink. But self-expression isn’t something you can be worthy of, rather it’s a birthright for existing. A byproduct of processing life. A state of being. It only feels like a radical act because we’ve been taught to seek permission. It’s a lesson I’m trying to relearn in adulthood because when I look back, kid me already knew. She never bothered to get that pen license.

Artwork by Hope Corrigan

I knew, even before the story revealed it, why Chicory was hiding. Just imagine for a moment the pressure of having to paint the world! The weight of making everyone’s existence more beautiful. The prestige of The Wielder title. Sometimes I can barely bring myself to put paint on a simple canvas no one else may ever see, because of the idea that I’m not good enough. If I break through this, it often comes as an act of defiance, as though I’m screaming back at all the things inside me telling me no.

This is what Chicory: A Colorful Tale is really about: artists, or perhaps more accurately, people. When it even feels like the question of ‘is it art?’ is being raised, the rightly slaps down a ‘YES’ down before it’s even fully articulated. When you’re making something that is definitely, and unquestionably art, the next logical question is ‘Am I an artist? Am I even good enough?’ Chicory has a lot more time to explore that, and that’s what makes it so impactful. The answer is still a resolute affirmative, but then it takes you warmly by the brush and says, ‘If you want to be. Let me show you why.’

4 Stars: ★★★★

CHICORY: A COLORFUL TALE

Developer: Greg Lobanov, Alexis Dean-Jones, Lena Raine, Madeline Berger, A Shell in the Pit

Publisher: Finji

Platforms: PC, Mac, PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5

Release Date: 10 June 2021

The PC version of Chicory: A Colorful Tale was provided and played for the purposes of this review.