To help reflect on the year that was, GamesHub has asked contributors, Australian game developers, and friends of the site to talk about some of their favourite games or gaming-related highlights of 2021. Ring of Pain’s Simon Boxer and Unpacking’s Wren Brier gave us some of theirs, as well as ACMI curator Jini Maxwell and games researcher Brendan Keogh. Games producer and consultant Meredith Hall is next.

Meredith is a multi-award-winning producer and marketer. Currently an independent creative, Meredith supports the games industry locally and internationally with production, business development, marketing, and accessibility consulting.

She is ex-Film Victoria, the cofounder of Accessibility Unlocked, Communications Director & Lead Producer on

You can follow Meredith on Twitter: @merryh

When I spoke to my partner about writing this article, I admitted I was struggling — in a lot of ways, this year had blended in so deeply with 2020, and I didn’t have all that many highlights come up to draw from. One thing he mentioned was the absolutely brilliant time we had with a certain multiplayer game, and both of us assumed this had occurred in the height of lockdown.

In 2020, we all grew pretty accustomed to lockdown. Animal Crossing, Tiger King, Dalgona Coffee – all these things and more punctuated the beginning of our pandemic experience, back when it was two weeks work from home. So what happens when over a year has passed, you’ve had a brief taste of freedom, and suddenly you’re plunged back in?

For a lot of people, many who are Victorians like myself, early 2021 had finally felt like things were starting to shift towards a new normal. My partner and I managed to have a wedding in April after postponing for a year (and being one of the lucky ones who only postponed once, in the end), cases hit zero (and stayed that way for weeks). I was seeing family, friends, feeling good and hopeful, but still enjoying the flexibility and safety working from home consistently provided me as a disabled person.

So to have it spin entirely out of control once more, to be waiting for a vaccination that felt so far away, to not be considered eligible despite my disability, and having very few games on my list that I was looking forward to that were also close to releasing — 2021 felt rougher, somehow. I was incredibly privileged in multiple ways (and I’ve spoken to many game devs about their own sense of ‘positive guilt’ in being able to continue working relatively unaffected by the pandemic itself) but having our collective hopes rise only to be dashed again, really hurt.

Thanks to the massive hit of 2020, many AAA studios (and indies!) were postponing or delaying releases once promised, work output had slowed industry-wide (not because of work from home as some places would like you to believe, but because of An Entire Pandemic), and motivation to play anything was at an all-time low, anyway.

Enter, Valheim

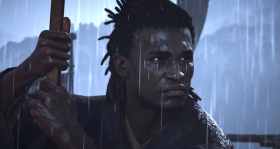

I’m sure you’ve played it, but Valheim came out in early Feb of 2021 in Early Access (and still is in EA to this day), as an exploration and survival game. It plays with Norse Mythology, spooky enemies, crafting and building, and is truly what you make of it.

The strangest part about sitting down to write this is that I so deeply associate the game with the pandemic, and yet all four of us (my husband, his brother and wife) played it when we were able to go anywhere, do anything. In planning a wedding, life gets pretty stressful pretty fast, but the four of us were jumping on almost every night to engage in whatever portion of the gameplay we found most exciting.

We’ve played games as a four-stack for years – from Destiny, to Divinity Original Sin 2, to Battlefield, to obscure indie titles — almost anything we can get our hands on. Every year, we hold our own Game of the Year awards, including a category for our best ‘Buzz Buzz moment’ — that is, the best or funniest moment from our gameplay together that year (and we like bees, okay? It’s a whole thing).

However, as each year creeps on, finding a game that suits us all gets increasingly harder. They have a daughter now and as it turns out: kids take up a lot of free time. We all work in relatively demanding fields, and we all need different things from games. I like crafting and generally making a home, and also collecting pets — making me a relatively useless contributor to combat, because I want to instead build a pen for the creatures I find on the bottom of the sea in Scrap Mechanic.

My partner likes challenging dungeons, raids, complicated puzzles, and so does his brother. My sister-in-law tends to enjoy everything in varying degrees — planning, combat, building, and more. All three of them like horde modes, whereas I’d rather play competitive Overwatch than wave-based shooter-style PvE games most of the time.

Valheim was a perfect blend of everything we each individually needed from a game, and for whatever reason, became deeply associated with lockdown for us all. I think it gave us a space to explore beyond our means — while the world had reopened, we still had a sense of insecurity and nervousness about planning anything, doing anything, going anywhere. Valheim however, felt stable in its instability – going out in real life still felt a little abnormal and restrictive, but online felt the same way it always had.

It gave us moments of laughter, surprise, and progression. It was as complicated or simple as we each needed to make it at any point in time. Having something where the rules were straightforward, but the world was ours, gave us something that the real world couldn’t at that point in time — a sense of freedom that felt secure. It even motivated me to make my first video compilation in 2 years, something that I used to love doing whenever we picked up a game.

It was exactly what we needed when we didn’t know we would need it, and when we slowly fell off it in favour of something new as we often do, we all agreed it was special to our 2021.

Games and TikTok

TikTok has long appeared a daunting space to most people over the age of thirteen, and I understand why. The speed at which it communicates, the time to milkshake duck — it’s beyond anything I’ve ever experienced. It’s a lawless land, filled with dance trends and songs subverting into memes that turn into storytelling structures that turn into art that turn into god knows what.

When I was younger, I remember recording absurd things with friends as well as solo — vocal auditions performances, dance routines, stories. There is a video of 18-year-old Meredith auditioning for The Glee Project. Yes, it is horrifying. No, I will not show you.

We uploaded most of these to closed spaces, or showed no one — cringe was heavy in our systems and we knew the potential for mockery was rife at all times. Being sincere online was something to be embarrassed about. Being sincere in general was embarrassing — we were all sarcasm, all mockery, all ‘too good for that’ when it came to trends — all the while filling out our MySpace surveys and sharing heavily edited photos.

TikTok however, happens to be the most genuine platform I’ve engaged with maybe ever — once you train it. Launching it is wild — you will see impossibly pretty people doing impossibly fluid dances and question every joint in your body. A few days of scrolling though, and it will be making you laugh, making you think, or even trying to act as a quasi-therapist (if you end up on mental-health-gay-TikTok like me, anyway).

People don’t often hide behind anonymity. People are kind and encouraging. They speak to you, rather than at you like Twitter, and thankfully they never just yell blindly into the sun like Facebook. There’s a sense of community, of purpose, always within reach, and cringe culture almost doesn’t exist. There’s no shame in posting a video of yourself saying something stupid. I’m not here to debate the legality or inherent ‘goodness’ of TikTok, but I am here to yell about what it has done and can do for games.

TikTok as a platform has a uniquely targeted organic content system. Because of this, it is a space that is ripe for game developers to directly reach an audience without paying a cent. I’ve seen a number of teams now, some known to me who I’ve encouraged, others on their own steam, who have had a go at just ‘throwing a clip up’ on TikTok and then seen views reach the millions, without a cent paid.

@2ptint #indiegames #physicsfun #gamedev ♬ Starman (2012 Remaster) – David Bowie

Obviously visibility is great, but what’s really exciting is the level of conversion it’s having for a lot of teams. Downloads spiking, wishlists rising — all able to be connected to specific videos going viral, even when the call to action is gentle.

Devs I know are now running 10k plus accounts with direct reach to their players. Even for smaller posts — some people are like ‘aw, my videos only get 300 views’ — that’s often 300 more views than you ACTUALLY got on Twitter. At least for a moment, a second, you were the only thing on the screen — try again next time, but it’s still a start.

Others, like the Landfall TikTok run by my wonderful and clever friend Hanna, have hit 10 million likes cumulatively, and are nearing 750 thousand followers. With a combination of direct conversation with their community, using trends really well, asking questions of the team, or showing an insight into them as developers, they’ve created a space that has a little bit of everything for everyone, and it has clearly paid off.

@landfallgames Reply to @bubbafrank1 #gamedev ♬ I Just Wanna Know – Luke Reeves

It is one of the most powerful community management and advertising tool we have right now as developers. This isn’t to say it’s perfect. If you don’t get the tone exactly right, if your game doesn’t have the aesthetic sense that the audience is looking for, if you don’t post enough, if you feel too corporate, the list goes on — all these things can stop your videos from doing well.

It is a grueling, time-consuming thing – but it’s the kind of time-consuming that has a potential for a reward that is so much higher than almost any other platform independent game developers have available to themselves right now. People are eager to know you, to know what you’re passionate about. It isn’t cringe to share what you’re working on, nor will you be slammed for self-promotion like Reddit — it’s a space MADE for sharing, MADE for honesty, MADE to be sincere.

This is so exciting to me as it is another avenue to destabilise the monotony and monopoly of paid content. Sure, smaller creators will always struggle for airtime, but we saw what discovering posting gifs (as opposed to still content) did for so many indies on Twitter. We saw what smaller directs did for surfacing new and exciting games.

This feels like a new opportunity, a space where video games are naturally engaging, easier to discuss, threads can be followed, and algorithmically, your audience will be brought to you. Naturally, over time, like anything else, the space will fracture and oversaturate, but for now? It’s pretty damn cool.

Chicory

Chicory was sold to me the moment I saw it years ago — a cute little dog painting in a gif, coloring the world around them. A great mechanic, a fun-looking story, something bright and upbeat. What I didn’t expect when it finally came to playing it, however, was an allegory for a life in the creative industry — a conversation around imposter syndrome, depression, and anxiety around your output and impact. Nor did I expect to be playing it at such a strange time in my life.

If you don’t know me, you don’t know that I spent the last three years of my life at a state government agency funding local video games. When I started there, I was so afraid my relationships would change — that people would treat me differently, people who had once ignored me would want to be my friend, that suddenly my title would be more important than who I was.

I was going from a small, indie producer to someone partially responsible for supporting the industry on a much larger scale. You would think that this would make moving on easy — surely, responsibility would be shifting and changing and at a ‘smaller’ scale. But instead, when I was staring down the barrel of moving on, the same fears gripped me.

Would anyone want my time, if they suddenly had to pay for it? Would they want to include me in conversations, when I was just me, not backed by an incredible agency? Do I actually know anything at all? Do I matter? I felt that I had a responsibility in that role — just like the wielder in Chicory — and understanding how that would change when I stepped away was harder than I imagined.

Chicory managed to capture the fears we all have so eloquently, and I truly believe it is a must-play for anyone living a life in creative pursuit, especially the hopeless pursuit of perfection. Throughout the entire game, both Chicory and you as the player character are forced to reflect on their role in the world — where their worth comes from, who they look up to, and why.

As an industry, so much of our work is attached to our sense of self-worth. Being a developer and a person often feel inextricable from one another, and the need for a capitalistic sense of output within an often unwieldy creative pursuit can be a daunting track to tread. Additionally, our work can often be intertwined with an admiration for developers around us, and when you first start in the industry this can make it exhausting or terrifying if people you’ve pedestaled change, or grow, or leave the industry, or just are people.

Moving on from my role and re-understanding my place within the industry as a whole meant a lot of reflection on how to continue to make space for others, how to wield influence carefully, and what my responsibility to the industry is.

Chicory explores how we leave a legacy in a way I’ve never really seen done before. Chicory forces you as a player to stop and truly recognise that everyone is doing their best, is afraid, believes their work isn’t good enough — and more than anything else, that the people you put on a pedestal are actually your peers.

I’m lucky to have a number of people around me that I still look up to, but it’s no longer in an unreasonable, unrealistic way. We make space for each other to be fragile, angry, afraid, nervous, shy. We talk about how adrift we feel. We articulate the darkest, scariest, spookiest spaces in ourselves. We look at our personal perceived failures in the face, together, and tell each other that it’ll be okay.

This isn’t even beginning to touch on the existential fear of the year, around climate, the pandemic, work culture, and more — there’s a conversation in Chicory about political theory, capitalism, and labour that is one of my favourite in-game moments of the year — but sometimes it’s enough to just share those feelings. I don’t think I would have survived 2020, nor 2021, if it weren’t for being surrounded by such talented people who were telling me they were scared too.

Playing Chicory at the time that I did rewired my brain. I don’t want to say too much about it as it’ll spoil it, but its ability to force me to look inward and recognise my own fear — and walk forward anyway — was something that truly shaped my 2021.

It’s okay to ask for help — and often, it’s the only way to survive. It’s okay to be afraid — but you should keep going, anyway. It’s okay to be tired, and disappointed, and sometimes even a little bit ashamed — but you are always going to be your harshest critic, so what happens when you turn some of your compassion inward?

In a year where so many of us were feeling more worn down than ever, it was a gentle, kind reminder that color and hope is always around, but sometimes you have to be the one to wield it.

For more of GamesHub’s Best of 2021 content, have a look at our picks for Best PlayStation Games of 2021, Best Xbox Games of 2021, Best PC Games of 2021, Best Nintendo Games of 2021, Best Mobile Games of 2021, Best Australian Games of 2021, our overall Best Games of 2021, and our Game of the Year for 2021.

Our spotlight on personal highlights includes Ring of Pain’s Simon Boxer, Unpacking’s Wren Brier, ACMI curator Jini Maxwell, games researcher Brendan Keogh, the 2021 Wordplay mentorship participants, producer and consultant Meredith Hall, GamesHub content lead Leah Williams, critic David Wildgoose, contributor Chris Button, and Nicholas Kennedy, host/content creator Jess McDonell, SUPERJUMP Editor-In-Chief James Burns, and GamesHub Managing Editor Edmond Tran.