In 2021, it’s easy to access decades-old video game magazines thanks to community archives and databases like Retromags and the Internet Archive. Old issues of Computer Gaming World, Nintendo Power and PC Gamer are available to read or download for free online because of community-led projects like these.

But a while ago, I saw an image online of a magazine cover that I’d never seen or heard of before. I recognised the

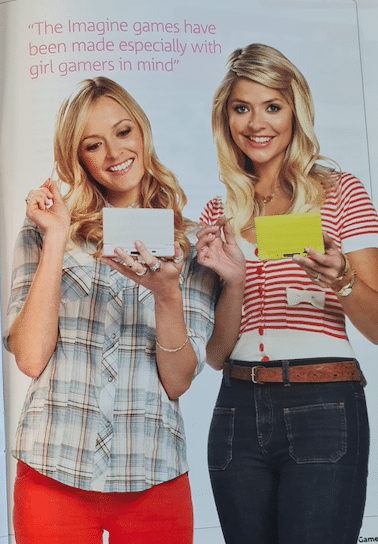

The title, ‘Girl Gamer,’ was printed in bold, pink lettering, and it featured a photograph of a young woman, beaming at the pink

Over the next few months, I experienced first-hand the exciting highs and frustrating lows of searching for old media.

Valuing Girls’ Gaming Histories

The Issue 02 cover image had circulated around the press in 2008 around the time it was published, but I was disheartened by its treatment. Several articles critically or outright mocked the gendered content on the cover, while providing little information at all on the content inside its pages.

The cover is admittedly cheesy; there are ample shades of pink and it promotes some fairly conservative gender roles with games like Cooking Mama featured centrally. At the same time though, this was a magazine dedicated to girls – a demographic of video game players that had been overlooked by the industry for years.

The gaming histories of girls have also been overlooked.

Now, they’re being traced more closely through initiatives like Rachel Weil’s Femicom Museum, which aims to ‘[reimagine] the history of femme electronic games and toys’ while celebrating a policy of ‘No “pink sucks!” vibes!’

Read: What can games tell us about girlhood?

Raven Simone’s recent and popular YouTube documentary on the lost Mean Girls DS game also tells a captivating story about 3DS games for girls, licensed titles in the era, and the trials and turmoils of locating lost media.

In the past, girls’ games have been frustratingly relegated as frivolous and sexist, and then dismissed as illegitimate historical objects. These attitudes make it difficult to learn about digital gaming cultures for girls.

Searching for Girl Gamer

No online magazine databases held copies of Girl Gamer, nor were they available on any second-hand marketplace platforms. This meant I had to start from scratch with basic Google research. I was able to easily find out that Girl Gamer was released in the UK between 2007-2009, was published by Future PLC, and that it was packaged for free with UK pre-teen girl magazines, Bliss and Mizz.

With this small amount of information, I reached out to anyone who could tell me more about the publication. I left messages with Future as well as Bliss and Mizz’s parent company, Panini. I also left countless messages to former Future employees who worked for the company at the time of Girl Gamer.

I joined lost media Discord channels in the hopes someone may recognise the magazine, but my posts quickly slipped into the void. I also reached out to gaming preservation initiatives, Femicom and the Video Game History Foundation.

Most of my messages went unanswered. Those that did respond were sorry they couldn’t help me, but I was at least starting to learn why Girl Gamer was so difficult to track down. The Video Game History Foundation told me that Girl Gamer had flown under their radar because of its distinct packaging with Bliss and Mizz. Unless collectors already knew to look, they were unlikely to consider those specific magazines.

Meanwhile, I learned that The British Library had copies in their collection, but only to visitors of their reading rooms. They weren’t willing to make an exception for transfer. In-person archives already raise accessibility limitations, and COVID-19 has only exacerbated access. This roadblock was especially frustrating: sitting in The British Library meant that Girl Gamer technically wasn’t lost media, I just had no means of accessing it from Australia.

Australian Localisation

Ironically, when I’d put a pause on the search, I had my most promising breakthrough. By chance I’d mentioned my search to a colleague who happened to know someone that had worked for Official

I had a delightful chat with Mark Serrels, who was happy to try and answer my burning questions. He confirmed that it was a small promotional publication for pre-teen girls and that the Australian localisation would likely have also been packaged free with other girls’ magazines. The content would have been similar to the UK version, but with new editorials written by local freelancers. Sections may also have been added or edited to better speak to Australian girls.

Serrels then got me in contact with current Future employees who searched the company’s records for archived Girl Gamer PDFs. I was told that normally copies of past magazines could be pulled up in their system, though sadly nothing on Girl Gamer showed up; another mentioned it possibly predated their archives.

With renewed energy for my search, I began to reach out to several ONM and Future employees based in Australia at the time of Girl Gamer. I also reached out to the local games community to learn more.

Thinking I might discover more about the Australian localisation, my social media posts unexpectedly reached people in the UK who’d worked on the original Girl Gamer. Mostly men had reluctantly written for the magazine, recalling their discomfort with its stereotypical content. One even shared that he’d elected not to have his name printed in Girl Gamer for this reason.

In hindsight, I should have consulted my online network much earlier. It was uplifting to see my call shared so readily and widely. The story of Girl Gamer was finally starting to come together. Meanwhile, earlier that same day, I’d also connected with a hobbyist collector who held in their possession Issues 1-8 of Girl Gamer!

Inside Girl Gamer

The collector generously shared photographs of several Girl Gamer pages — I could barely contain my excitement.

Like my original reaction to that first Issue 02 cover image, I was instantly struck by its consistent saturation of soft and pastel pinks. Its marketing function aside, I wasn’t used to seeing games publications exclusively addressing girls. I couldn’t help but appreciate the unconventional pairing of femininity with video games.

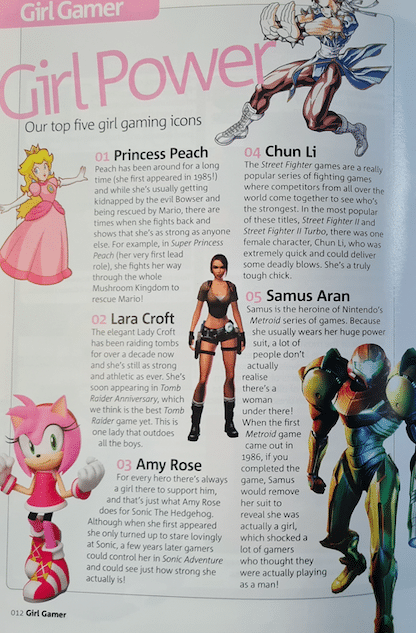

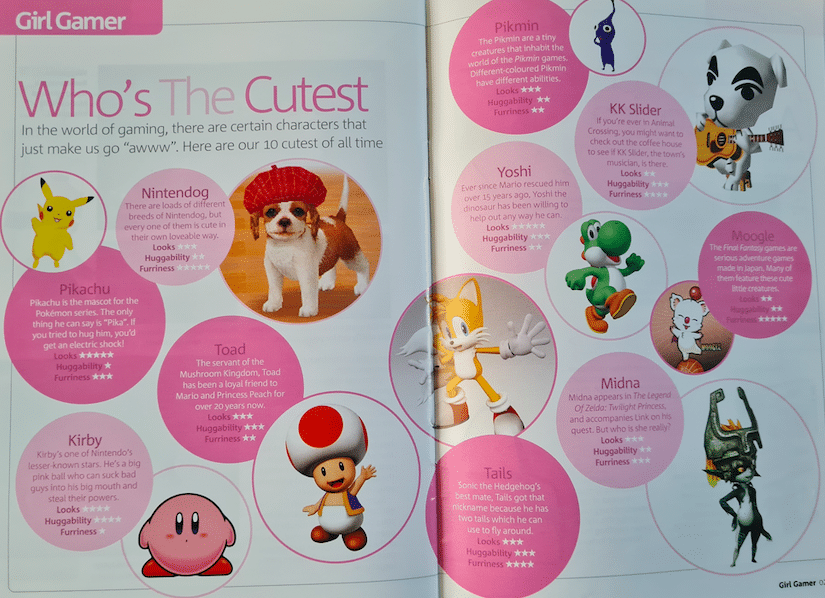

Despite the relentless gendered presumptions with its targeted terminology, Girl Gamer’s presentation of gaming was uniquely feminine, warm, and welcoming rather than boyishly aggressive. There was also a centralisation of dating, dancing, and cooking games that simply weren’t valued in mainstream gaming magazines. A memorable segment in Issue 02 even amusingly evaluates the ‘looks,’ ‘huggability,’ and ‘furriness’ of popular game characters out of five stars, from Pikachu and Yoshi to Animal Crossing’s KK Slider.

Even though we can now access past gaming magazines with relative ease, the process of obtaining them in the first place can be far from simple.

Despite my efforts, I’m still yet to have acquired issues or PDFs in full to share online or donate to an institutional collection. Nor was anyone connected to Future Australia able to confirm whether the Australian localisation ever officially went to print.

There’s a number of reasons that Girl Gamer has been so difficult to find.

It was a small promotional publication, it was packaged with other magazines, and it was largely derided by the mainstream gaming community.

Magazines are cultural artefacts and like all artefacts, they tell stories. Girl Gamer represents an era where pre-teen girls were seen by

Player-Favourite Gambling Guides

We’ve handpicked our latest and most visited guides covering online casinos, betting sites, and more—for every kind of player.