In the foyer of the Malthouse Theatre, the feeling is one of puzzled anticipation. People are unsure of what type of experience they are about to walk into. The doors to the Merlyn Theatre open and they are filed into separate groups, being ushered down a narrow, claustrophobic hallway, headsets lining the walls for them to pick up. I was taken down a hallway and waited with a large group of people, anxious for the show to start, and for their questions to be answered. Then, the lights went dim, the wall to the right opened, and we all took our first steps into the world of Hour of the Wolf.

The week before, during Melbourne International Games Week, John Robertson returned to PAX Aus with his extremely popular theatre show, The Dark Room. While Hour of the Wolf’s non-linear theatre experience felt reminiscent of “walking simulator” games, The Dark Room is more inspired by text-based adventures. Both shows involved direct audience participation to drive their narratives, and are part of a growing sub-genre of theatre shows that draw from video games to foster engagement.

A yearly standout of PAX Aus, The Dark Room is a unique blend of comedy show, text-based adventure game and choose your own adventure novel with the ever-so-slightly maniacal John Robertson guiding the way. In the interactive show that I attended, John picked an audience member, rushed over to them and handed them a microphone. That person had been chosen to enter The Dark Room where they were presented with four options that determined where the show would go next.

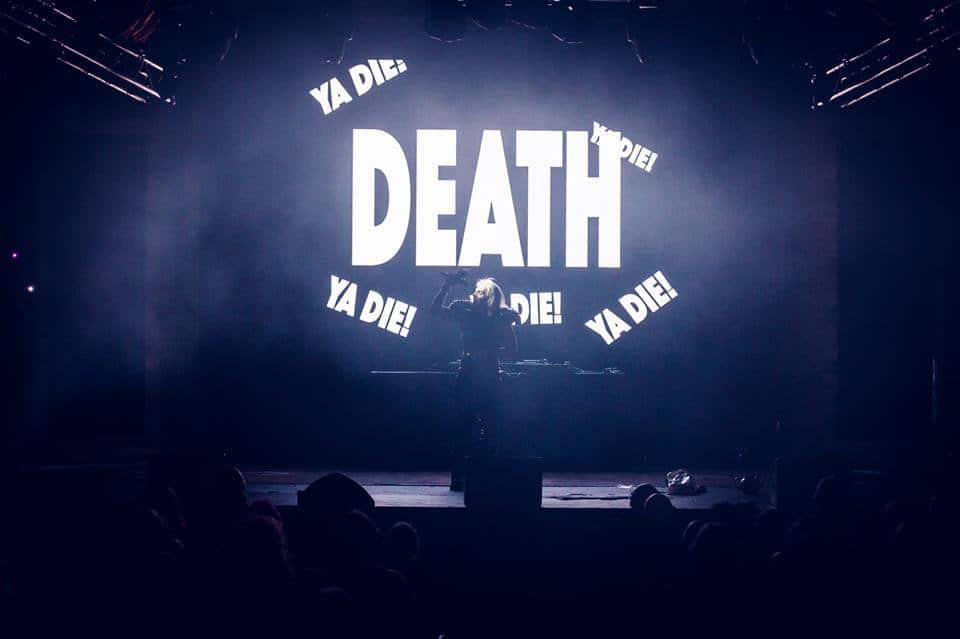

While all of the options led to a different story with completely different choices, the end result is always the same. Whether it was by accidentally activating a deceptive bomb or licking a light switch that causes electricity to fry their brains, the audience member is killed in The Dark Room and the audience chants “Ya Die! Ya Die! Ya Die!” along with Robertson. As a finale, John turns to the entire audience and brings everyone into The Dark Room. Everyone votes on what to do next by cheering for their preferred option, with the entire audience being responsible for what happens next.

“I think of it more like a party than a game or a show”, Robertson told GamesHub, reflecting on his performance from the night before. “Everyone in that theatre has value to me, whether they’re someone who’s just sitting there and enjoying themselves or someone who gets to play. But, to me, the joy is the bit when everyone gets to do both.”

Robertson, who has been performing and iterating on The Dark Room for more than ten years, said that there are multiple versions of the show that he performs, depending on who the audience is.

“Sometimes I might just do a show that’s just for a spectacle, like there’s always an ending in there”, he said. “And sometimes I really bake in a hard narrative.”

“I did a show [with a really intricate narrative] and the audience didn’t find the bloody thing”, he said with a laugh. “I made all of these special new things for them and they never saw it, they just got the dumb jokes. But they had a great show, so I don’t care.”

While The Dark Room combines the interactive narrative format with a stand-up comedy show, it is not the only medium in which this has been tried. Interactive narratives have allowed plays to create a whole new submedium that makes the audience a part of the story and not just an outside observer. The show Hour of the Wolf by Matthew Lutton and Keziah Warner, uses the interactive narrative format to create an experience that explores what interactivity can do for plays.

In the show, the audience is guided around the many landmarks of the fictional town of Hope Hill where every year on the winter solstice, the longest night of the year, a figure known only as Mrs. Wolf stalks the townspeople between the hours of 3:00-4:00 AM. During that time, it takes something important from the villagers, whether it be a physical item, an aspect of their personality or something more sinister. The audience can choose to either follow characters around the town and follow their story or solve the puzzles hidden around Hope Hill to find the deeper story buried within the narrative. At the end of the hour, the clock rewinds back to 3:00 AM and the audience has the chance to follow another story.

While incorporating an interactive narrative into a play has been explored before through shows like Sleep No More in New York and Melbourne’s own Love Lust Lost, Hour of the Wolf is unique as it draws inspiration from video games such as The Stanley Parable and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture.

Much like those games, the audience is encouraged to go on their own journey through Hope Hill and uncover the story over time rather than having every piece of the story presented to them immediately. David Harris, who as the interactive dramaturg on Hour of the Wolf helped shape the show around the interactive elements present within it, said there is a lot of crossover between video games and interactive plays.

“I think the major element [present in interactive plays and video games] is that both forms place the audience as the center of movement and location attention”, he said. “In a traditional narrative video game, nothing happens without the audience kind of moving towards it. It’s much like an immersive or interactive theatre experience in that nothing happens until the audience moves towards that space as well.”

However, there are limitations in bringing audience agency to theatre. The main one that creators have to contend with is that audiences may miss entire sections of the story. In a video game, a player can simply replay the game to find out all of the narrative elements they may have missed on their first playthrough. However, much like with The Dark Room, Harris had to contend with the fact that audience members would most likely never experience the full story present within Hour of the Wolf. Audience members could either follow the actors to find out their story, or focus entirely on solving the puzzles, like I did. But the length of Hour of the Wolf makes it impossible to do both in one session.

“In immersive theatre, there’s a massive phenomenon of people missing out on entire scenes and entire plotlines because they didn’t get to the right place at the right time”, he said. “That FOMO really builds and pushes certain audience members away.”

There’s also the issue that audience members don’t always necessarily act in the way that has been planned for.

“As any good GM [game master] knows, as soon as you put someone’s agency into a story, they will generally try to fuck it up”, joked Harris. “Agency is only as good as the medium is made flexible to hold it.”

However, Harris is still extremely excited about what the future will bring when incorporating audience agency into other forms of narratives.

“I just think we’re in such an exciting time where mediums and cross-disciplinary works are being made all the time”, he said. “I think theatre would be a fantastic ally in the development of a more interactive and more playful age.”

This article was commissioned by GamesHub and Creative Victoria as part of Wordplay, a games writing mentorship program held during Melbourne International Games Week 2023.