A perfect, musical moment occurs in The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies, directly after King Thranduil declines to dispatch his mighty force of elves to support the dwarves at Ravenhill. Bilbo assures Gandalf that he can warn Thorin of the approaching orcs discreetly, and so the tender, daring Shire theme (from 17 seconds) briefly transforms into rising semitones (at 27 seconds). An astute listener understands what Bilbo is suggesting; that he can disappear from the Seen world if he slips the One Ring onto his finger.

The ring theme, by Howard Shore, is acutely recognisable, which is why Bilbo doesn’t need to say the word ‘ring’ for his plan to be understood. The musical theme doesn’t even need to be stated in full, just hinted at with a dissonant presentation of its very first interval. If you’re a fan of blockbuster films, you will be familiar with the clever ways in which musical material is presented.

In games, music is delivered via interactive structures and so, while you will absolutely hear themes to depict characters, places and narrative ideas, they may unfold in ways that are not so predictable. Nonetheless, Planet of Lana is also built around musical moments as perfect as any you’ll find in a Hobbit movie.

So, how is a musical theme created and used in a game medium? Composer Takeshi Furukawa, provides some delightfully unexpected answers.

Finger painting

Planet of Lana has almost no dialogue or text, so music bears a heavier-than-average storytelling burden. The game opens with the mass abduction of Lana’s village, but there is much more to the offending robots than is initially made clear. Furukawa explains that the only direction he received from developers was to hint at this hidden, narrative complexity, via use of melody.

When I reviewed Planet of Lana at release, I thought the robot theme had been planned extremely carefully. I’d imagined a composer prototyping intervals and rhythm for maximum flexibility, to allow for arrangement across wildly contrasting scenes. Incredibly, Furukawa says he “sucks” at creating motifs and his process is more like “throwing paint against the wall” to see “what a melody might become”.

“That five note robot melody wasn’t like, ‘I’m going to come up with the main theme’, let’s do it. It was me tinkering on the piano, putting ideas against images and moving things around,” he said. “My older daughter had just started learning the piano and I wanted to write something that she could play, so it was a conscious choice to make it as simple as possible.”

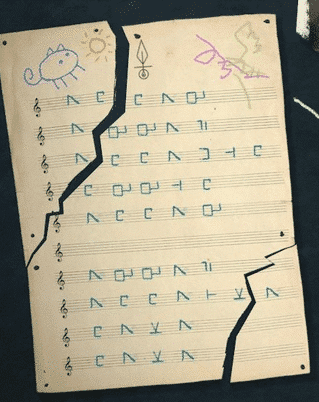

When I look at a score Furukawa provides, it indeed looks like it belongs in a beginner piano book. The five fingers of the right hand remain in one position, while the left stretches to play an achievable fifth and only moves over small distances – a minor third at most.

From little things

So, the soundtrack for Planet of Lana sounds like a kid playing the piano? Not exactly.

Listen to Furukawa (the senior) perform his piano theme here and then keep listening as Desert Chase unfolds. The soundtrack does not sound like a kid playing the piano, it sounds like a terrifying 90-piece Hungarian Studio Orchestra in relentless pursuit of you, atop some kind of Mad Max-inspired War Rig.

There are definitely lessons to learn about how the best musical themes are accessible (including to children and beginners), but for now let’s examine the skill required to take a humble idea to such massive places.

When I mention to Furukawa that diegetic instances of this theme (those that can be heard by in-game characters) are in the key of G (usually heard as part of a puzzle to control a robot), he says, “One has to have very specific intent because musical key affects register, and therefore timbre and playability. For example, the trumpets have a specific range where they sound most brilliant and beautiful, so I set the music in the key of G taking such factors into consideration, and sound effects followed suit.”

Indeed, the original motif was created in Bb, with the idea that his daughter could grasp the piano’s black keys more easily. He says, “Clarity is undervalued. The more concise your orchestration is, the more the beauty of performance and emotion will come through.”

Furukawa’s scores are certainly clean. Lines are doubled, but there’s no space given to anything pointlessly complicated. Each part has a clear role and character. Consider the below excerpt showing the string section at a structural rise, in Desert Chase (listen from bar 18 here).

The robot theme is referenced in the violins (shown on the top two lines), but the rhythm is written quite differently, to allow the accompaniment to work in a complex triple meter; 6 groups of 3 (or the subdivided 6) notes per phrase (which becomes the ‘chase’ part of this piece in the following section).

A dominant impression

Without raising overt story-related spoilers, I think that the narrative complexity of the robots is neither captured by the tiny piano motif, nor the big orchestral sounds, but instead by harmony. Specifically, by the two chords and metric pause, for emphasis, at the ends of the first two phrases of the robot theme.

The A♭ major chord at bars 39 and 40 is built on the flattened 2nd degree of G major – and this is a very strong harmonic choice. (Hear this ♭II chord at exactly 1’20’’.) It implies the bold, yet curiously complicated, Phrygian dominant scale, before a comfortable resolution back to G major at bar 42. (Hear chord I at exactly 1’26.) This juxtaposition of ‘curiously complicated’ and ‘comfortable’ depicts the robots very neatly.

You will hear references to the robot theme and its harmony across the game, to explain robot behaviour, accompany backstory and as integral puzzle pieces. One of my favourite moments occurs when you find the robot theme transcribed into abstract notation. I’ve removed half of this screenshot, because (combined with some knowledge about the robot theme) it spoils one of the best secrets in the game.

Big things grow

Planet of Lana’s music is mostly delivered in “blocks” with either silence (filled with ambient sound) or level loops used as transitions between cutscenes. This allows for tight control over orchestration, as well as the opportunity to create detailed melodies and harmony.

Furukawa says, “I’ve figured out a method that works to help me straddle both the film and game worlds, where I initially throw paint and explore emotions, then sculpt, making sure that the music is presented in a clear, concise and logical fashion.”

Although this article has exclusively explored Planet of Lana’s robot theme, my ‘Hobbit moment’ actually occurred via a musical reference to Lana’s beloved cat-monkey creature, Mui. (Listen to Mui’s theme here.)

A few descending notes drew my attention to Mui’s fear of water and subsequent limitation as a puzzle piece, in exactly the same way Shore’s rising semitone reminded me that Bilbo was thinking about the One Ring.

It’s pretty cool that something as humble as a beginner piano melody could underpin a whole game soundtrack. It’s even more amazing that Planet of Lana’s most distinctive chord (A♭) was chosen because Furukawa (the junior) needed to move her small fingers to somewhere close by.

As skilled a craftsman as Takeshi Furukawa may be, he can still be inspired by his daughter’s developing ability as a musician. I hope she gets a chance to perform Planet of Lana’s robot theme in concert. If so, please join me in a front row seat.