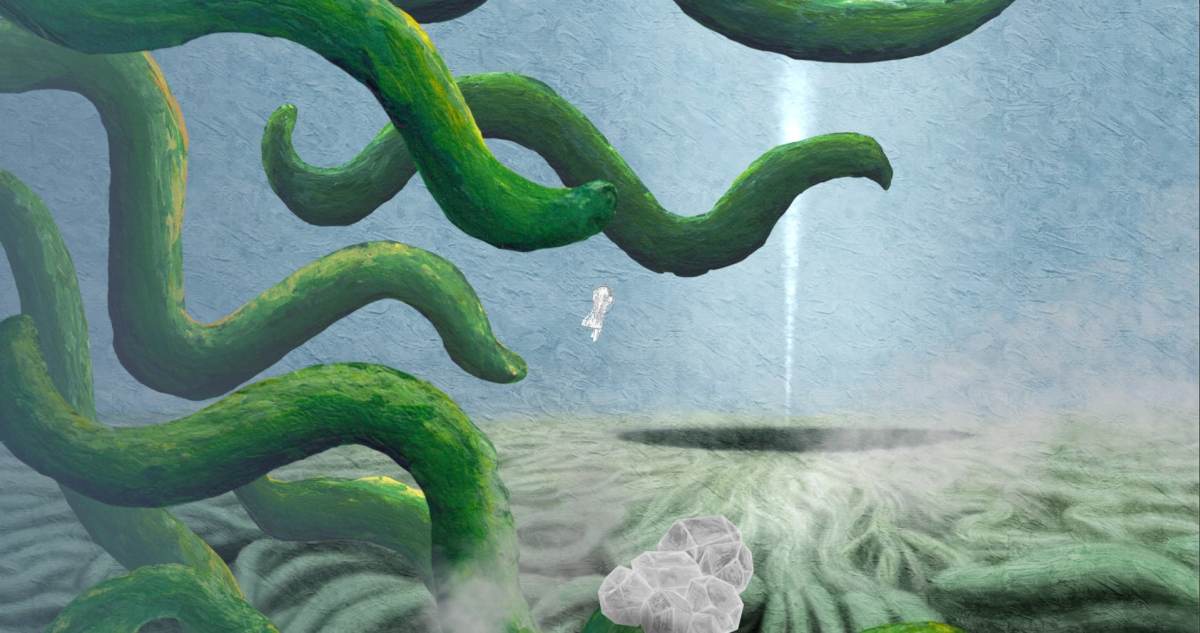

You’ll excuse me if I appear exhausted. I’ve had a busy day as… uh… the gal who works inside impressionist painter Claude Monet’s eyeball? There’s lots to do; navigate squiggly bits, push gunky balls around, ride fumes emanating from the many flecks of paint that he seems to have accidentally splattered into his delicate, ocular receptacle.

I also battled a typhoid monster (in reference to the serious illness Monet contracted as a young adult), and rolled a big red ball around for 30 minutes, before realising that it was a misplaced sun, from the genre-defining work, Impression, Sunrise.

So, yes. The Master’s Pupil is certainly amazing.

Easel-y Impressed

This vibrant experience first came to my attention at Noble Steed Games’ second Work In Progress night. I arrived late, during designer Pat Naoum’s compelling account of how he feared his house would soon be completely overcome with the physical assets he was creating for this fully hand-painted game.

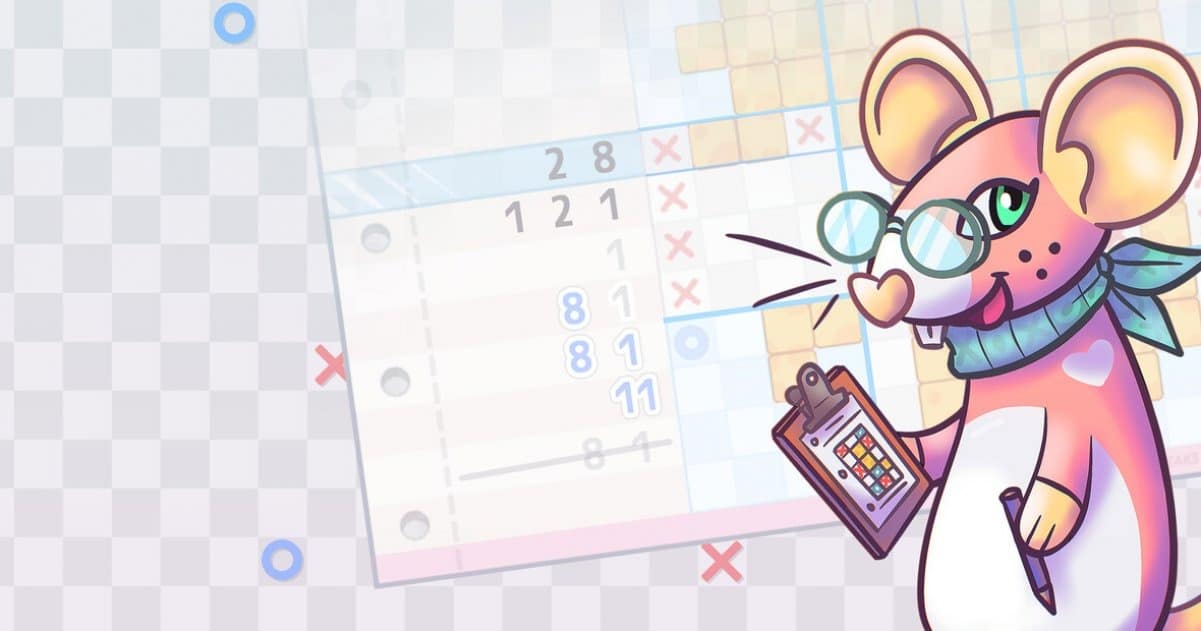

Naoum says, ‘I was originally going to paint assets quite large, but they had to be small. Each vine is now only about 5 mm tall. I constructed level pieces in-game first, then printed and painted them, meaning level design could be precise. For the background and foreground vines, I ended up using a modular system, just a whole lot of curves and joints.

‘I also used a film negative scanner for super high-resolution detail. You can actually see the dust on the scanner bed on the assets in Level 1, before I started to clean it properly!’

How long did Naoum spend painting? He says, ‘I’ve roughly estimated 2000 hours, but I think I’ll have to actually count the pages at some point.’

Was it worth it? ‘Everyone and their dog has a 2D, side-scrolling, puzzle game, so something that stands out makes all the difference. I am proud of it, and it’s good to finally use that creative arts degree.’

Read: How the Diablo 4 team tried to revive classical art for a new generation

Stroke of Genius

Once I’d come to terms with the excessive painting, I had one, very obvious, follow-up question; ‘Are you, like, a fan of Monet?’

Naoum says, ‘I came up with the idea of a game set in an eye first, after seeing some close-up photography of an iris. I started to wonder whose eye it could be, and how the game could span their lifetime. An impressionist game would stand out, and Monet had a fascinating life. He also suffered from cataracts, which could work for the game’s ending.’

Many puzzles are about reassembling Monet’s works, in ways that involve placement and colour. How does the train get to its destination (in Arrival of the Normandy Train, Gare Saint-Lazare)? First you flick some crystal switches, to change the direction of coloured paint fumes. Then you float a ball through deadly black crystals to flick the red switch. Then you become red, so that the part of the eye that sucks colour (?), possibly a ‘cone’, can suck the red from you, wither and make a red barrier disappear.

Upon re-reading that last paragraph, it might actually be best not to overthink puzzles. They’re fun to play, at least, and mostly involve allowing yourself, or other game pieces, to be painted yellow, blue, red, purple, orange or green, but never black. Or you’ll die.

The Master’s Pupil may be a platforming game, but (almost) every interaction is with physical elements; stacking, rolling, floating, colouring, switching and manipulating pieces.

Paint-staking Pursuit

The game does have occasional moments where things get irrevocably stuck. Naoum has created a reset function, so that you can replay just the last little section of each level, like when you’ve gotten yourself forever squished under a red boat from Red Boats at Argenteuil. It doesn’t have an overly excessive amount of these moments that I’d expect for a physics-based game, though – this kind of experience seems notoriously difficult to idiot-proof (the boat-juggling idiot being me.)

On a similar note, physics-based puzzle games can either feel like a meditative challenge, or supremely aggravating. Remember Blueberry Garden? I loved it, even while everything tumbled chaotically around, so I guess maybe it was one game that hit the sweet spot of being both.

Naoum has been careful to ensure the player’s experience is smooth and coherent. ‘Puzzle design is very strange, it’s essentially designing for frustration. A little too much, players will quit. Not enough, and players will be bored. But it’s the ah-ha! moment when you solve the problem that I was striving to create.’

There’s a lot to chew on here. I particularly appreciated the last few chapters, which added moving pieces to the formula. I enjoyed knowing some of what to do, and working out the rest via a process of elimination. Platforming became more dangerous, by way of the colour black, and there were more opportunities to fall, endlessly, into the void.

The ending then opened into wide, grand puzzles, spanning multiple scenes, and involving the dramatic movement of larger level pieces. I didn’t understand everything that happened, but the action was compelling enough to send me googling Monet’s final years, to find out what this evocative sequence may represent.

Eye See

Earlier this year, I was at Musée d’Orsay, in Paris, which is home to several of Monet’s paintings. It was fun to stand next to them, but also expensive, busy and punctuated by my kids making me watch, ‘Bro, you not The Thinker,’ videos on TikTok (Rodin’s The Gates of Hell, with its little Thinker, is at the same gallery).

If you’re interested in painting, The Master’s Pupil is a genuinely good use of your time and money. In addition to every single one of Naoum’s beautiful brush strokes, you’ll find 50 of Monet’s paintings, deconstructed, whole and presented as rewards for your hard work.

Perhaps I initially thought that Monet was the ‘master’ referred to in the game’s title, but Naoum has also now revealed himself as a guru of imagination and craft. For a unique experience, look no further.

The Master’s Pupil will be released on PC, Mac, and Nintendo Switch on 28 July 2023.