Australian game developers have a knack for finding the fun in moving house.

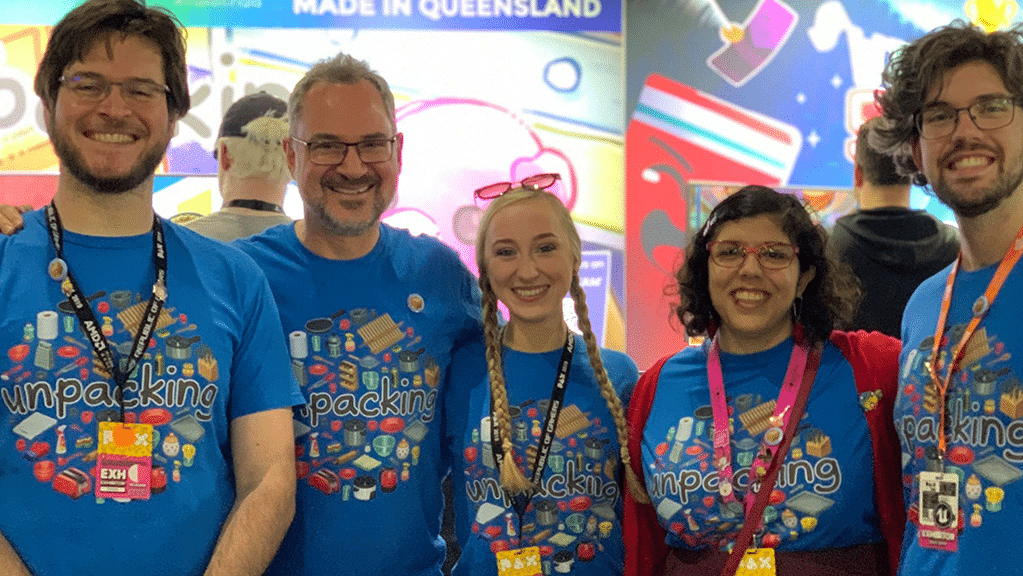

First, it was SMG Studio’s Moving Out, an Australian Game Developer Award (AGDA)-winning chaotic removalist party game. Now, it’s Unpacking – the antithesis of Moving Out – from Brisbane-based indie studio Witch Beam, a game about opening boxes filled with sentimental possessions and following a character’s life journey through the items they own.

It’s a complete 180-degree turn from Witch Beam’s debut game, Assault Android Cactus, a twin-stick arcade shooter known for its frenetic action and bullet-hell stylings. Although seemingly different to its predecessor in every way, Unpacking represents growth, as well as the growing relationship between two of its lead developers, Tim Dawson and Wren Brier.

Witch Beam’s beginnings

Witch Beam was founded in 2013 as a result of the systemic issues plaguing large development studios. Harsh working conditions, poor communication, leadership without vision: all challenges Dawson faced at varying points during his career.

‘Ultimately, it was being frustrated with the studios that I’d worked at,’ Dawson said. ‘Looking back on it, there’s this interesting pattern where I always found really cool people at studios I’ve worked with that felt really like-minded that really wanted to do cool things for the game. And there were things that were holding us back or making it more difficult to do that than we’d like.’

His first game development foray was with former Adelaide studio Ratbag Games, where he worked on The Dukes of Hazzard: Return of the General Lee for PlayStation 2 and Xbox. Following this, Dawson spent time with several notable Australian-based teams including Pandemic Studios, Tantalus Media’s now-defunct Brisbane office, and a stint working on Team Bondi’s ambitious detective title, L.A. Noire.

After the late-2000s global financial crisis, many of Australia’s large game developers shut down local operations.

Japanese video game company Sega held an Australian office, which remained open longer than most. During his time there, Dawson met several colleagues who would go on to become founding members of Witch Beam. While working on various projects at Sega, he built a strong rapport with designer Sanatana Mishra and composer Jeff van Dyck.

Unfortunately, despite strong relationships with colleagues, Sega was a difficult workplace, highlighted by the cancelled Golden Axe project – which was publicly dredged up last year by Sega without consulting those who worked on the prototype, as explained by Dawson on Twitter at the time.

When Sega Australia closed in 2013, it was time to go indie. Assault Android Cactus, Witch Beam’s debut game, launched in 2015 to strong reviews but it ‘was not a massive success’ commercially, according to Dawson. It sold healthily over a long period of time, however, boosted by multiple console ports and promotions with various companies, recouping costs and allowing Witch Beam to continue as a small studio.

For Brier, her career prior to Unpacking was primarily in art, creating assets for various games including for fellow Brisbane studio Halfbrick and their popular Jetpack Joyride and Fruit Ninja games. This work saw her involved in live ops, helping to create post-launch content. Aside from Halfbrick, Brier also produced art for various other projects, some of which never saw the light of day.

With Dawson and Brier were both heavily involved in Brisbane’s game development scene, it was inevitable they would cross paths sooner rather than later. When they eventually did, it sparked a new era for Witch Beam – and the start of a relationship.

All’s fair in love and video games

Dawson and Brier first met in 2016 at a BIG Dev meetup, a regular networking event for Queensland-based developers. At a later event, Brier played a demo of Assault Android Cactus for the first time and was so impressed she messaged Dawson to ask if they could catch up.

‘I hadn’t actually played [Assault Android Cactus] before,’ Brier said. ‘I ended up buying it when I got home, started playing and I hit him up like “oh my god, Tim, can we meet up and can I pick your brain about this? Because I want to know more!”‘

What followed was a coffee catch-up lasting five hours, continuing elsewhere after the cafe closed. The pair become a couple during Melbourne International Games Week (MIGW) after spending most of the week together.

‘Our whole relationship has been very intertwined with games and [MIGW] and game development,’ Brier said. ‘We didn’t intend to develop a game together for three-and-a-half years – it just happened. We just wanted to do Unpacking as a little side project for fun, because we’re both developers, we’re both artists – we always wanted to do something together for fun on the side.’

Although Unpacking started as a small side project in early 2018, the cosy object arrangement game is now firmly on international radars. Brier came up with the game’s concept after the couple moved in together and unpacked stacks of unlabelled boxes – ‘my packing style’, Dawson cheekily remarked. The act of opening a box, not knowing what was contained within, and clearing out the contents before moving onto a new box felt like a game to Brier, prompting Dawson to help her flesh the idea out.

‘Tim, for as long as I’ve known him, he’s always really encouraged me to come up with ideas for games, because he’s always coming up with game ideas, and I’m less confident with that,’ Brier said.

For Unpacking, she took on a creative director role, leading the game’s adorable art direction, and sharing design duties with Dawson – her first professional designer credit.

Part of early development included participating in the Stugan accelerator program in Sweden.

Stugan is a not-for-profit initiative that sees a group of game developers spend two months in an idyllic woodlands cabin, away from the busyness of life, working towards a specific project milestone. A few months after Stugan, at the start of 2019, Unpacking entered full development.

Finding the fun in unpacking boxes

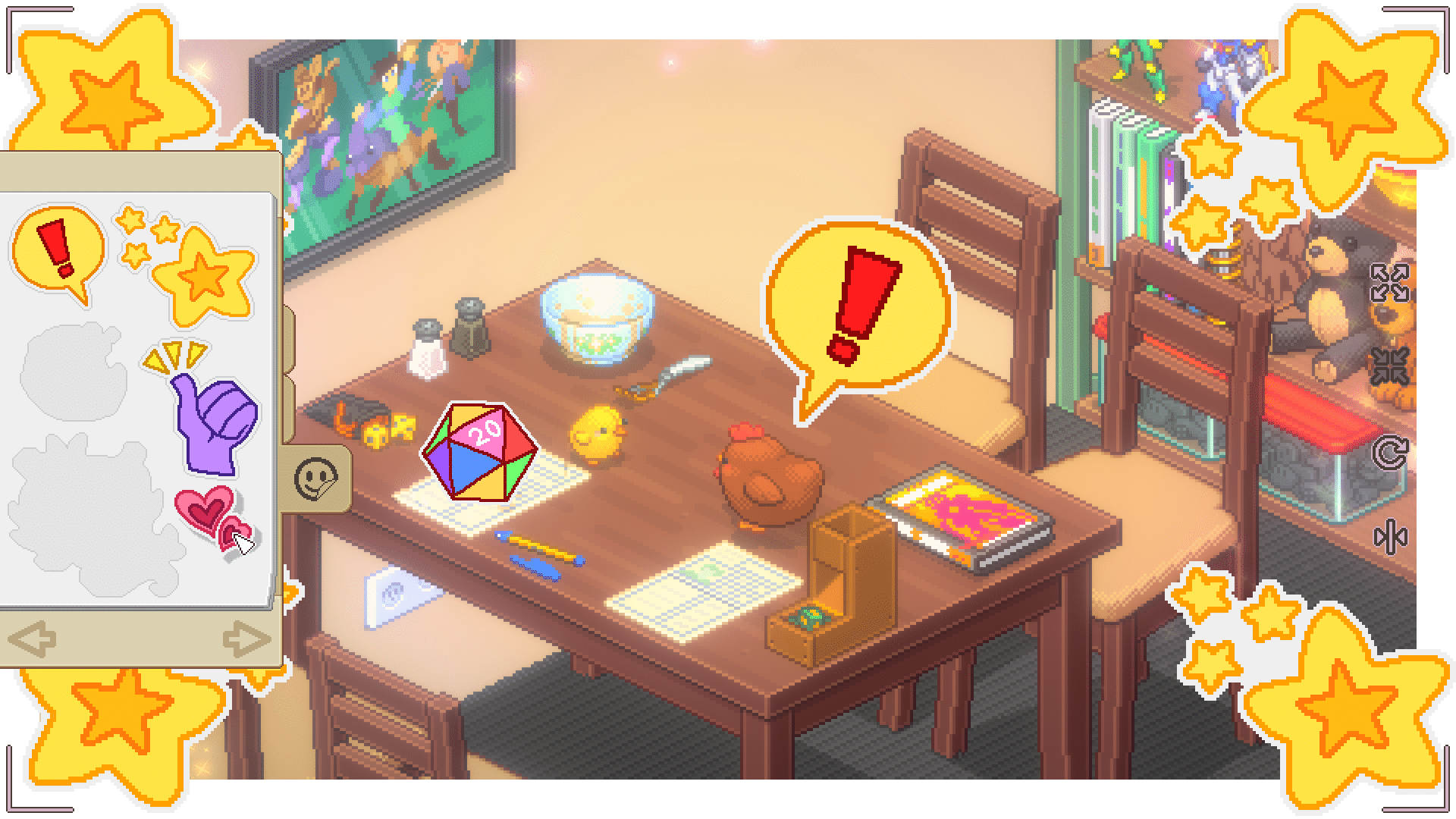

Unpacking encapsulates Brier’s favourite video game elements: surprise and delight, something she describes as ‘a very

So when the idea came to Brier as the couple unpacked boxes, it seemed natural to make a game tapping into that same sense of surprise. The act of opening a box, retrieving and placing possessions, and then proceeding to a new box once emptied already had a clear element of game progression.

Dawson mentioned he enjoys finding the challenge in game development and working through solutions, believing ‘good design is good design’ regardless of genre.

For Assault Android Cactus, he had to think about factors such as how to balance the number of projectiles versus a player’s ability to dodge them, and visual readability including how to use colour to effectively communicate safety and danger at a glance.

From an art perspective, Brier and the small team of artists put an astounding level of detail into the visuals. When she worked on the fast-paced Jetpack Joyride, the readability of visuals was the focus and the game’s quick movement allowed for more flexible asset reuse. Unpacking‘s comparatively static pace didn’t permit such a luxury. More than 1,000 unique items and 35 different environments were hand-crafted for the game.

‘[All the artwork is] completely unique because each of these environments, a player spends so much time in it that it needs to feel distinct, and the player will definitely tell if these environments are “samey” or repeating because of that,’ Brier said.

Dawson also explained how he leant on a similar approach to that of Assault Android Cactus, which he described as having a three-act structure, telling a story through design, including where and what types of enemies appeared to instil a sense of progression. Similarly, Unpacking may seem random to someone playing for the first time, but each box and possession housed within is specifically placed to craft a narrative.

‘It seems really simple because [Assault Android Cactus is] an action game…but there’s a sense of theatrics to it,’ Dawson said. ‘That we’re trying to tell a story through the medium of enemy spawns. And then with Unpacking, we’re trying to tell a story through the medium of item orders – which can be done in any order the player wants, but we control it to a degree.’

‘You can tell a lot about a person from the items that they own – that was a thought that we kept coming back to,’ Brier added. ‘Whatever comes of that, whatever items you end up with in a room, kind of tell a story about the person living there.’

When asked what story their possessions would tell, Brier and Dawson paused for a moment. Dawson broke the silence first, suggesting someone would conclude ‘that we’re both nerds’, while Brier added they might think the couple is ‘working harder than we should and making a huge mess’.

Thinking about the couple’s belongings prompted Dawson to discuss how different combinations of possessions can tell interesting stories. He pointed to the bookshelf in the background, where two copies of the same animation textbook sat, which inspired them to think about how combinations of items in Unpacking could tell stories – and create light-hearted moments.

One such in-game example mentioned was the scenario where you find a single boot, but not the matching pair, until the very last moment in a totally unexpected location – a deeply relatable problem to anyone still finding lost items years after moving house.

Designing for everyone

Prior to release, Unpacking won two AGDAs: Game of the Year, and Excellence in Accessibility. While both are impressive awards in their own right, it was clear early on in development that Unpacking was a deeply accessible experience – especially for children.

In the couple’s time at Stugan, visitors would come and playtest games. It was a multicultural environment where some of the visitors – especially children – didn’t speak English, which wasn’t a barrier to enjoying Unpacking due to it being a mostly wordless experience.

‘It really struck me: why do we need to bog [Unpacking] down with text when people can play it without?’ Brier said. ‘It also might have to do with my history with games when I was a kid.’

Hebrew was Brier’s first language, a dialect not represented in games when she was growing up.

‘When I was really young, any games that I played that had a lot of [text] – basically all of that was invisible to me,’ Brier recalled. ‘I could not parse it, so it may as well not have been there.’

‘I remember learning years later that say, Super Mario 64 had a whole lot of text explanations on how to use the controls. I thought it was all intuited because that’s what I had to do – I couldn’t read anything! So knowing that’s some kids’ experience, that makes me want to accommodate that as much as I can.’

Perhaps an early sign of Unpacking‘s popularity with younger players, when Witch Beam exhibited at AVCon in Adelaide, one young girl played the demo three times in one day, returning the next day to play it three more times. Her feedback afterwards? That the first level was a little bit easy!

Beyond language and reading comprehension barriers, Unpacking meets many of the video game industry’s gold standards for accessibility: fully remappable controls, adjustable zoom levels, and no inhibitive timers. Dawson mentioned that while it was important to design Unpacking in the most accessible way possible, features integrated with accessibility in mind often benefit way more people than intended.

‘A lot of the features ended up being kind of like a curb cut…those little slopes built into curbs were originally cut in for wheelchair users, but they’re usable by people with shopping trolleys, prams, bikes,’ Dawson said. ‘It’s the example of an affordance for someone with a specific disability that ends up actually just having general utility for everyone.’

He pointed to the example of Including various levels of zoom, which help people with sight-based disabilities, while also allowing anyone to enjoy the pixel art visuals in more detail, regardless of barriers. Dawson explained that developing according to accessibility standards is simply ‘good game design’.

Dealing with sudden popularity

Social media and virality informed much of Witch Beam’s decision to pivot Unpacking from a side project to a game worth full production cycle commitment. Early promotional GIFs rapidly gained popularity online, attracting a community of potential unpackers. It turned out despite the act of moving house generally being a loathsome task, many people loved the idea of neatly arranging pixel possessions in a video game.

Although Unpacking‘s scope didn’t change in the wake of popularity during early development, it informed some of Witch Beam’s decisions around publishing and marketing. Already having an established audience helped pique interest among potential publishers, which wasn’t quite the case with the self-published Assault Android Cactus.

Back before Assault Android Cactus launched, Witch Beam entered discussions with prospective investors late in development; one partner was considered but ultimately wanted too much in return.

‘They were talking about paying us a lot but they also wanted additional features and multiplayer, online multiplayer, and things like that,’ Dawson said. ‘But it all fell through and didn’t pan out that way. So it was exciting on Unpacking that we were having this interest come to us. I knew that was unusual: normally you have to hustle harder to get people to respond to you.’

The relationships established during the Assault Android Cactus days did help, along with Witch Beam having a moderately successful title to its name.

”[Having already released Assault Android Cactus], I think that gave us more opportunities, a lot more open doors, and funds to work on Unpacking,’ Brier said. ‘I feel Unpacking is definitely like the little sibling Cactus helped raise.’

Witch Beam signed with Humble Games, the publishing arm of charity bundle storefront Humble Bundle currently owned by IGN Entertainment. Melbourne developer Simon Boxer’s Ring of Pain, and the Australian-made Wildfire are also signed to the label, which has also published global indie hits such as Slay the Spire and A Hat in Time.

‘[Humble Games was] very straight with us in a lot of ways,’ Dawson said. ‘A lot of the negotiations didn’t feel like they were angling to try to get as much as they could have.’

Brier added they appreciated Humble’s approach of wanting ‘to reach a partnership’, as opposed to the horror stories of predatory indie publishing deals discussed among developers in hushed tones. Humble also had knowledge Witch Beam didn’t, including an understanding of the Asian video game market. Another benefit saw Witch Beam maintain ownership over their brand and voice, so Brier continued to run Unpacking‘s popular Twitter account.

Read: Unpacking review – A poignant reflection on the ups and downs of life

But with Unpacking‘s popularity showing no signs of slowing, the team recognised they needed help. Brier met Canadian community management specialist Victoria Tran, who was then working for Kitfox Games during Boyfriend Dungeon‘s development, at PAX Australia 2018. The pair hit it off and expressed admiration for each other’s games, exchanged merch and kept in contact.

Tran continued to be a public fan of Unpacking, streaming the demo and even offering advice to the team on how to attract more visitors to the game’s Steam page. When it came to enlisting a community manager, Brier reached out to ask if Tran knew of any available colleagues. Tran unexpectedly put her own hand up, despite already working for Innersloth on Among Us, one of the world’s most popular games.

Witch Beam arranged for Tran to work one day a week, overseeing Unpacking‘s Discord server, TikTok account, and email newsletter. Brier described a small amount of Tran’s time as being ‘equal to a lot of someone else’s time because she’s that good.’

As part of Tran’s successful TikTok strategy, one video raced to over a million views showing Unpacking footage paired with the divisive age-old question: which way should the toilet paper roll go?

At the time of our interview, Brier and Dawson were in the awkward limbo stage of having finished work on Unpacking while counting the days until launch.

‘It’s a weird state for an indie developer – it feels very different to working in a big studio where you ship a game and obviously you hope it does well, but you’ll be months onto a new project by the time anyone tells you if it’s sold well or the reviews are good,’ Dawson said.

Brier described the strange feeling of checking off each final milestone as feeling like ‘another last goodbye’.

‘I was saying to Tim the other day that this feels like the end of high school because I don’t have anything else that I’ve done that was this long to compare it to,’ Brier said.

‘We’re about to have our big graduation ceremony and go out into the world!’

Unpacking is out now on PC,