Screen Australia recently announced major new funding support for 27 game creators living across Australia. It’s one of the largest funding cohorts for the organisation, which is ramping up support for Australian-made games as part of the Australian Government’s new National Cultural Policy. Per Lee Naimo, Screen Australia’s Head of Online and Games, the concerted effort is about allowing Australian creativity to flow, while also opening up skill pathways.

“Being a cultural agency, the artistic side is really important to us. But we also want to be helping to create skills and jobs and sustainability,” Naimo told GamesHub. “If we’re achieving what we want to, in the next five, 10, 20 years, we’ll see a much more diverse, experimental, and supportive industry as a result of funding … The ambition that we have is to see the industry continue to grow and diversify.”

Screen Australia is a unique organisation in that it’s designed to support Australian-made games as a whole, while also collaborating with state-based funding bodies, including VicScreen, Screen Queensland, and Screen NSW. Naimo believes it’s important for developers to be able to create from where they are, without moving state-to-state to chase funding opportunities. Where few opportunities exist, Screen Australia aims to provide a helping hand.

According to Naimo, each state-based cultural organisation shares knowledge and aims, collaborating to best ensure support for the arts, country-wide. Developers who apply for Screen Australia funding may already have funding from VicScreen, Screen Queensland, or other bodies – but Screen Australia functions somewhat as an inner net.

Read: Screen NSW announces Digital Games Seed Development Program

“It’s not a requirement to have other funding in your finance plan to come to Screen Australia,” Naimo explained. “It can often help, because we can see that someone else – be that in the form of a state agency or a publisher, or an investor or private capital – has jumped on board. But a lot of the times, we are one of the first pieces of the puzzle, which is okay, too … We all have overlapping but seperate priorities.”

One of the priorities for Screen Australia is a wonderful elevation of weirdness.

While Naimo highlighted the tangible awards presented to developers as being great examples of the success of funding – for example, Fuzzy Ghost’s Queer Man Peering Into a Rock Pool.jpg being nominated at the Independent Games Festival (IGF) Awards in 2023 – what is more important for the organisation is fostering creative ideas.

“One of our real goals in establishing these two funds [the Games Production Fund and Emerging Gamemakers Fund] was to support those weird, experimental, risk-taking games,” Naimo said.

“That’s something that we see as our role – to be able to support people and their vision, and the kind of games they want to make. The artistic merits that they hold – be that something quite commercial and commercially viable, or something really, really weird.”

Read: Sydney game developers are getting weird, despite the risks

“Often at the budget scale that we’re operating on, with these lower budget games, weird is what cuts through. Weird is what gets people’s attention. Weird is how people express themselves, not just as game makers, but as the audience that plays those games. We’re really here for weird.”

“We often say – find your weird, and bring it to us.”

While Naimo was quick to clarify that ‘weird for weird’s sake’ isn’t quite the same as expression through the weird, he encouraged game developers to explore the weird, and wield it “in a way that is specific, and expressive, and personal” to their practice.

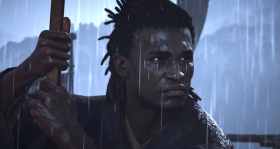

What is most novel about the recent announcement from Screen Australia is the amount of genuinely weird games now supported with Australian Government funding. Winnie’s Hole is a prominent example. In this body horror adventure-roguelike, you control the viruses living inside Winnie the Pooh’s body, transforming him to “refine his primitive form.”

It’s a terrifying-looking game, and incredibly weird, but Lee Naimo says Screen Australia was endeared to the project for its artistic and creative merit, and that all-important sense of weird.

“It’s very hard to deny the audience traction [of Winnie’s Hole],” Naimo said. “It’s a little bit of a bait-and-switch – I feel like the virus infecting Winnie the Pooh is the weird hook to get you in, but the game itself is really excellent, and really compelling, and actually really heartfelt.”

Notably, the team behind Winnie’s Hole went through two applications with Screen Australia before Winnie’s Hole was successfully funded – but this is something Naimo encourages. Listening to feedback, reiterating on design, and reapplying with stronger, more well-thought ideas increases the chance of gaining support.

“We really, really like and appreciate when developers take our feedback on board, and implement it,” Naimo said. “It makes a big difference.”

Mystiques Haunted Antiques is another example of a weird game that hooked Screen Australia – a game that follows four “terrible women” looking to save an antique store by developing psychic powers.

“Just the way the game is presented – it’s about the four worst women that you’ve ever met – this is the kind of game that we should be supporting, the kind of voices that need to be elevated. It’s a really cool game,” Naimo said.

“Creatively, these games really tick that box and our assessment criteria of exceptional creativity, and also [they’re] really distinct.” For Naimo, the confidence backing each funded project was also essential. “Great games, no matter the scale of them, [should] really be self aware, and know what they’re trying to say, to capture in gameplay, and audience experience. That’s something you really sit up and take notice of.”

For Naimo, being able to foster the growth of these games, and allowing developers the runway to tell their stories, is its own reward. At Screen Australia, he’s uniquely positioned to boost Australia’s games industry, and have the necessary conversations to ensure its future growth.

Read: Puzzling and exploring inside the hand-painted eyeball of Claude Monet

“Being here at the Australian reception at GDC [as of our interview], and seeing a bunch of games that we funded showcasing, and having conversations with publishers, other investors, platform holders … seeing the impact of that firsthand is so gratifying,” Naimo said. “Seeing those conversations happen, and those careers advance.”

According to Naimo, funding for one particular project – The Master’s Pupil – led the game’s developer Pat Naoum to additional funding for future projects, and monetary support that will provide stability for his next steps.

“We helped him get across the finish line of a game that he’d been hand painting for over seven years, to release it to market, and to get the attention of different platforms – to then use that success to make his next project,” Naimo explained. “Those tangible results are excellent … It’s really hard to articulate just how privileged this role is, to be able to support people in achieving their dreams.”

Naimo himself was a recipient of Screen Australia funding in previous years, and he’s confident in saying that it changed his life, for the better. Now, he’s looking to pass that on. “I’m really lucky I get to help people,” he said.

You can read more about the latest Screen Australia funding round on GamesHub.