Making video games in Australia is hard. While support exists – in the form of government grants, tax cuts, public showcases, and more – creating a video game requires, passion, stubbornness, a hefty amount of talent, and the will to keep going beyond any obstacle.

At the South Australian Game Exhibition (SAGE) 2024, local South Australian developers discussed the art of game development on stage, and what keeps them motivate to create, even through tough times. On the panel was Chantal Ryan (We Have Always Lived In The Forest), Heidi Borge (CinnaDev), Leo Cheung (Paper Cactus Games), and Edee Korhonen-Bannister (My Colourful Mind), with Chad Toprak (Screen Australia) moderating.

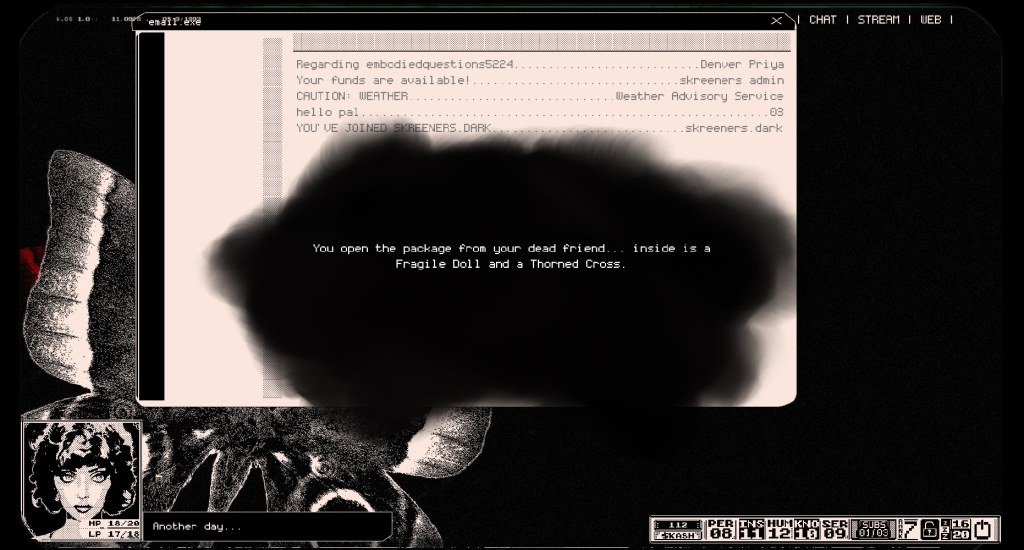

All four developers on the panel are currently leading work on assorted creative projects: Ryan is developing horror game darkwebSTREAMER, Borge is working on narrative farm sim Delphinium, Cheung is working on deckbuilding RPG Fox and Shadow, and Korhonen-Bannister is working with My Colourful Mind on a game focused on positive psychology.

While each had different paths into game development, many of the challenges and rewards they spoke of were shared – funding was highlighted as an important goal, but what was considered more important was the intangible impacts of creating games.

Read: SAGE 2024 showed off the full scope of South Australia’s game studios

“Getting funding is clearly a pretty huge success, going to Gamescom and being able to show off projects … just the fact that [our projects are] having a positive psychological effect is the goal,” Korhonen-Bannister said. “It’s very cool to see that, and to be able to spread the wonder that is game making to a wider community of people.”

Community was a frequent touchpoint during the discussion, with developers describing games as a means to foster community, and understanding. Through games, developers are able to connect with an audience, sharing their own passions, talent, and ideas.

“For me, the most exciting thing [about creating games] was when I got people to actually play the game for the first time,” Borge said. “I really, really care about the story and characters, so actually getting to send out my game to people and have them be like, ‘Oh, I love this character, he’s so funny’ – it was really, really special for me.”

Borge said that having community involved in the game was essential – as games are by people, for people. They’re designed to be played, and they become their own reward when played by others.

“Up until that point [of showing it to players], I have no point of reference as to whether it would actually be fun for people to play,” Borge said. “It’s very nerve-racking, but very exciting to send the build out for the first time.”

Cheung shared similar experiences, describing the process of creating and sharing games as liberating. “[My greatest success] has been being able to find my people, to be able to geek out about art, and about game design, and to be able to geek out about what [Paper Cactus Games] is doing.”

Read: What video game funding really means for local Australian developers

Ryan spoke openly about the on-paper success of darkwebSTREAMER – it’s appeared in the New York Times, won indie showcases at PAX, and achieved a steady string of financial support from government and non-government bodies. But despite the accolades and buzz around darkwebSTREAMER, Ryan agreed that it was community and personal engagement that made the entire experience worthwhile.

“I would say the thing that stands out for me echoes what the others have been saying – [my greatest success] was the first time we shared [darkwebSTREAMER] in public,” Ryan said.

“I intentionally set out to make something that no one had ever seen before, that felt like something no one had ever played before. That’s nerve-racking. You have no idea if anyone will like it at all, if people will connect with it. What we found was that we had 90 minute queues the whole time … they were so excited, and bringing their friends back.”

“Just that feeling that something that I was so passionate about was really connecting with people, and moving them, and making them feel something, and making them want to connect with others … the goal is always how we [the artist] make you feel. The fact that we were moving people to share, to come back, to spend that time – that’s why I’m making games.”

As Ryan said during the SAGE 2024 panel, the process is gratifying – although it’s not always “sunshine and roses.” Following discussion of the bright spots in game development, the panel turned focus to the complexities of the art: the trials and tribulations that are so worth pushing through.

In describing her work on darkwebSTREAMER, Ryan revealed numerous hurdles – changes to the game’s development team, initially not being able to adequately pay staff, securing funding, and ensuring stability. It was only on the strength of darkwebSTREAMER‘s existential ideas and Ryan’s passion for deep narrative that the project was eventually able to develop, and catch the attention of funding bodies.

“I didn’t have any money,” Ryan said. “That’s where Screen Australia came in. I will be honest … I don’t know if we’d be here today if we hadn’t secured that funding. That enabled me to hire somebody, one of the few people in the world who had the skills to come on in the middle of a project and pick it up, and begin finishing the game.”

Others on the panel spoke of challenges in refining their ideas, playtesting, designing for all kinds of players, and ensuring that games remain fun – even while they serve a higher purpose (for example, promoting psychological health management.) The panel also touched on more personal challenges in pursuing the creation of games: getting enough sleep, balancing work and play, and ensuring social connectedness.

“For me, it’s been about learning to work really consistently on the game,” Borge explained. “All of last year, I was still trying to figure out how to really get to a place where I could work every day on the game, and be happy with the work I had done … it’s just been about balancing [hobbies] with being a solo developer.”

To balance these needs is difficult – yet as Ryan, Borge, Cheung, and Korhonen-Bannister describe, the dangling carrot of releasing a game into the world, connecting with people, and sharing their creative ideas keeps them motivated.

Video game development is difficult. Even beyond gaining funding and support, there are so many hurdles to overcome. Yet at SAGE 2024, it was incredibly clear that despite the hardship, local game developers in South Australia (and no doubt across the country) are continuing to push forward, to strive further, in the effort to achieve their most ambitious goals.