Video game preservation is a complex art, one often held back by technical and intellectual copyright issues that can force historically-significant video games into obscurity. The question of how best to preserve video games is difficult to answer – and exactly what was puzzled through by prominent global historians at a recent panel for the Born Digital and Cultural Heritage Conference.

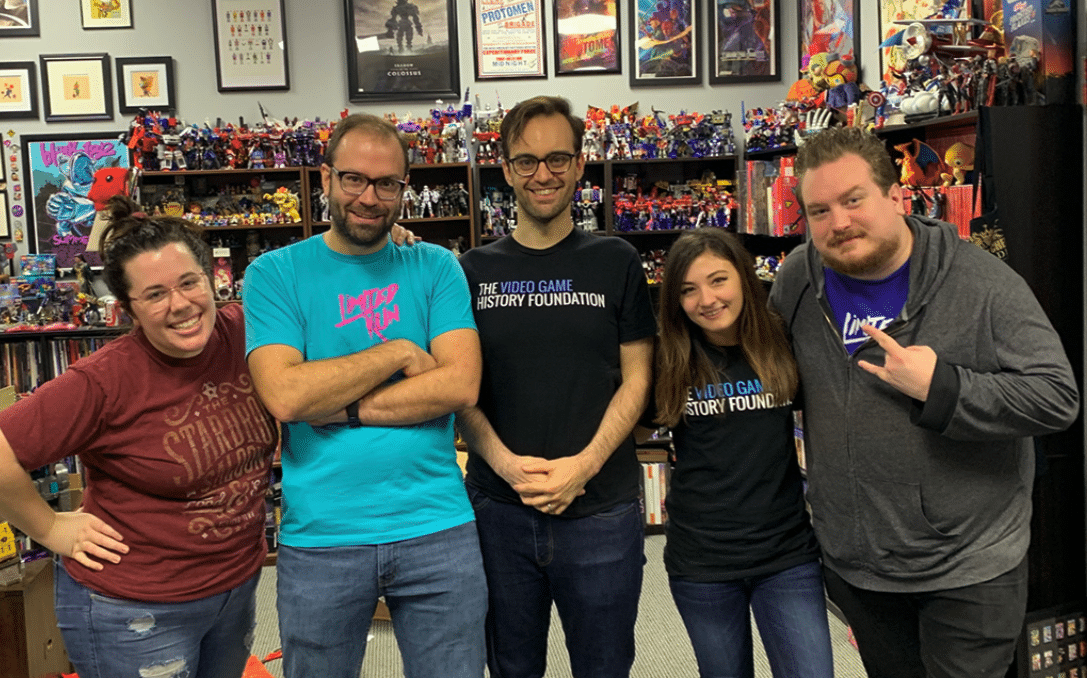

During the ‘Collecting More Than The Game’ panel, Nick Richardson, Head of Collections and Preservation at ACMI talked with Andrew Borman and Jon-Paul Dyson, who help run the International Center for the History of Electronic Games at The Strong Museum of Play, historian and archivist Frank Cifaldi, who runs the not-for-profit Video Game History Foundation, and Henry Lowood, a media and history curator for the Stanford University libraries.

Each had a unique perspective on why video games were important to preserve, and the best methods of preservation.

Games are for everyone

For Borman and Dyson, the most important part of preservation is ensuring physical and digital video games are accessible and playable for everyone.

‘We want people to be able to touch them, use them, learn from them,’ Borman said.

With over 550,000 items in the museum, and 65,000 dedicated to sharing the history of video games, there’s plenty of options for interactivity and engagement within the halls of the museum. While many museum spaces are guided by niche directives, which determine specific criteria for collection, The Strong Museum of Play aims to be the most comprehensive archive of video games and related paraphernalia.

To that end, the team have recently invested in a new laboratory to help preserve and back up video games – which often exist solely on outdated or unplayable devices. As Dyson makes clear, in another 30 or 40 years, even the video games on ‘modern’ consoles will be difficult to access, making now the perfect time to preserve such a young medium.

When media is not preserved correctly or treated with the reverence it deserves, it’s more likely to disappear from history. Video games represent unique art, technology and stories from the periods in which they’re developed – and it’s important for people to be able to play, view, and interact with this history.

‘All our exhibits are culminations of interactive artefacts and interpretations,’ Dyson said. To boost the museum’s collection, the team mostly looks for remarkable items, anything that helps illuminate deep video game history with the general public.

While Dyson acknowledged frequent technical issues with older devices, and intellectual property concerns from license holders, he believes preserving video games and having them be playable for everyone, is essential.

Read: Collecting the history of video games

More than just the product

Frank Cifaldi shared similar views – but disputed that games preservation was the major issue facing historians. Cifaldi’s Video Game History Foundation does not, in fact, collect video games at all. Instead, it celebrates and preserves their history, with a focus on collecting behind-the-scenes material, documentation and art as a means to educate current practitioners and fellow historians.

‘Access is an issue for video game history study, but it’s not the main one,’ Cifaldi said. Because emulators are highly accessible for everyone, he believes that conversations should instead focus more on how video game history can be preserved by historians, collectors, institutions, players and students sharing their experiences and knowledge.

Henry Lowood focussed on a similar issue, as he discussed how the Stanford libraries aim to make video game history better, based on three guiding statements.

These are that:

- Games don’t tell us how they were made

- Game don’t tell us how we played

- Games don’t tell us what we should think of them

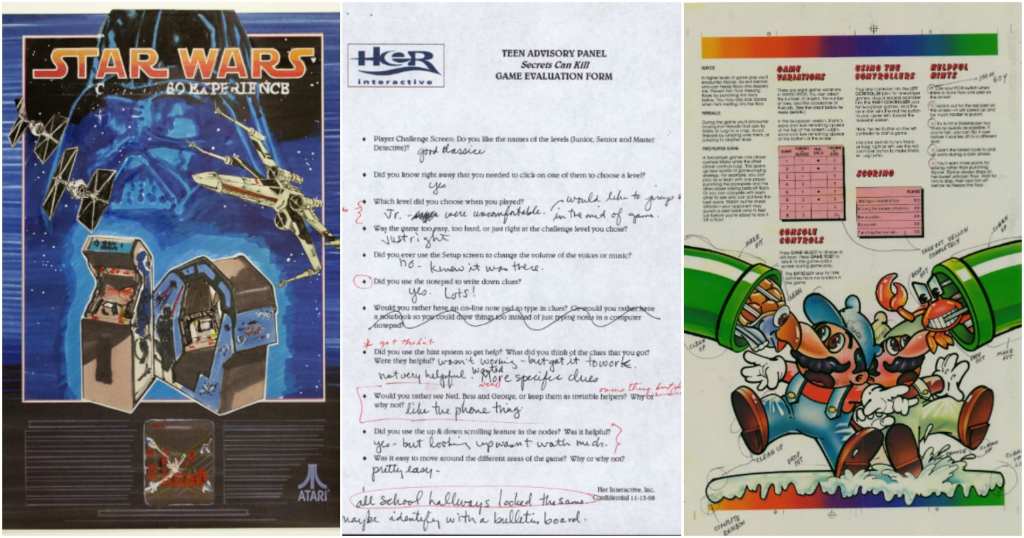

Essentially, Lowood believes that the culture and development behind games is essential to preserve alongside the actual, playable video game. Because we don’t know how they’re made, we need to collect and preserve documentation. Items like drawings, notes, photographs, objects, magazines, art assets and source code that can help illuminate how ideas for video games formed, and where design philosophies were implemented.

Not only can this help us understand video games, it can also help us understand the historical, cultural and technological context of the period the game was produced in.

In addition, Lowood notes that games must be preserved alongside information about how they were played, and what people thought of them. He believes that ‘accurate’ emulation pales in importance to learning where people played games – ie. in houses, in arcades, in other public spaces – and how this influenced their behaviour, interaction, and reaction to video games.

As Richardson pointed out, this extends to playing video games with family, fighting with siblings for controllers, or playing games at a friend’s house. While video games can be solo experiences, they can also be social activities, and reveal more about how we interact with each other, and how technology aids communication.

The panel made clear that to preserve a video game, it’s essential to think far beyond a cartridge, or a digital file. Video games don’t exist in a bubble – they’re social experiences, and often exist within historically-significant time periods. They can reveal more about how people live, what technologies existed at their fingertips, and how ideas have evolved and changed over time.

They are an essential part of human history – and it’s great to see preservationists working to ensure these artefacts are preserved in museums, where they can tell audiences more about modernity.

You can catch the entire ‘Collecting More Than The Game’ panel via VOD, or check out other talks from the Born Digital Cultural Heritage 2022 and Play It Again program here.