I’ve always been intrigued by the word ‘bittersweet’, and how two such opposite experiences, bitterness and sweetness, can not only exist simultaneously, but can intensify and enrich each other. It’s like being able to appreciate an event from a wide perspective; the good, the bad, and everything in between.

I’m not sure I would immediately describe Mr. Saitou as bittersweet, although it is. It’s more ‘suffer-cute’, the kind of unique combination I’d expect from Laura Shigihara. Her previous game, Rakuen, juxtaposed a gravely ill boy with an adorable fantasy world. After a troubled Mr. Saitou finds himself in the same hospital, silliness follows, and it’s just what the doctor ordered.

Read: Unpacking’s developers discuss homes as reflective and human places

Everything is funny

The game begins with a young patient sketching a series of crayon llamaworms, who then coalesce into a glimpse inside Mr. Saitou’s daily existence. He works in a button factory, producing what appear to be arbitrary puzzle pieces. His boss is obsessed with metrics and ‘creative whiteboarding’. One coworker talks too much, another is incompetent, yet coddled to the point that he feels important, and so on. It’s relatable.

Shigihara told GamesHub, ‘Before writing humorous dialogue, I try to let myself get into that really goofy zone, like when you’re 10 years old and at a sleepover with your friends. The later it gets and the more delirious, the funnier everything becomes.’

Amusement certainly gained momentum for me, from smirks to full-blown laughs. The excessive length of a crying llamaworm’s emoji tears is an example of how art contributes to comedy here, too.

In the office levels, I chuckled at a ‘button solo’, where the ‘pushed button sound effect’ cheerfully weaves itself into the musical composition. Shigihara is a composer, which explains music’s prominent position in the experience, but she is also director, writer, audio designer and coder on Mr. Saitou, as well as having created some of the art.

I even found Shigihara rapping on YouTube about ‘how to have a long day’, referencing the tongue-in-cheek llamaworm salutation, as well as a contextually related animated series, called Farmer in the Sky. A lot of love has been invested into this universe that spans games, and also mediums.

Storytelling is sincere

Although it’s certainly not necessary to have played Rakuen, those who have will recognise characters and locations. That said, there is an obvious difference between the two games, in terms of scope. Rakuen was lengthy, measured and complex, which felt important, given the intensity of its story. Mr. Saitou is about three hours long, and is able to make its point more concisely.

Shigihara told us, ‘With a smaller game, you can hone in on the protagonist. So even though you can’t go on as many wild tangents, you can really beef up what you do have.’

In writing the game’s final song first, she explains imagining what Mr. Saitou might be feeling, then using this track on repeat, to inspire story and puzzles, across the rest of the game. She says, ‘If game dev is the brain, music is the heart.’

Mr. Saitou is no less earnest than Rakuen, however. The protagonist’s dialogue often contrasts with the surrounding cuteness, providing an insight into his deeper feelings. Shigihara says, ‘The most important thing I consider, when writing serious content, is that it needs to be sincere. With both songs and dialogue, you really want to feel things in a genuine way and be able to communicate it to others.’

Musically, having noticed a complex bittersweetness to harmony, especially in character themes, I was interested in asking Shigihara how she arrived at this. She says, ‘I’m not sure that I choose chord progressions. When I’m in the right state of mind, the music just starts playing in my head and I have to try to ‘catch’ it before it disappears.’

‘The more genuinely I feel emotions, the more clearly I can hear the music, so when preparing to compose, I think a lot about how to get into that state.’

Continuity is key

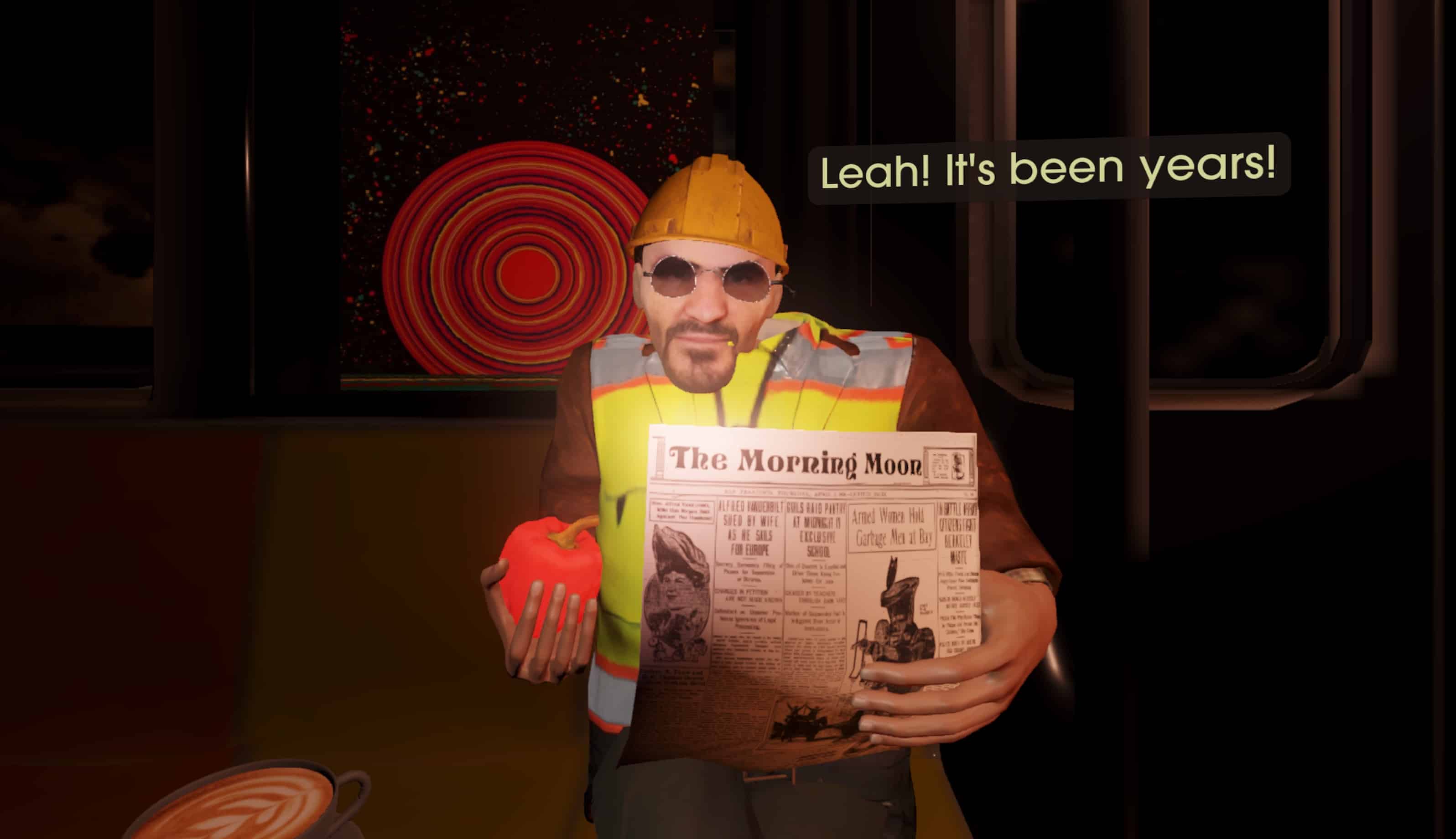

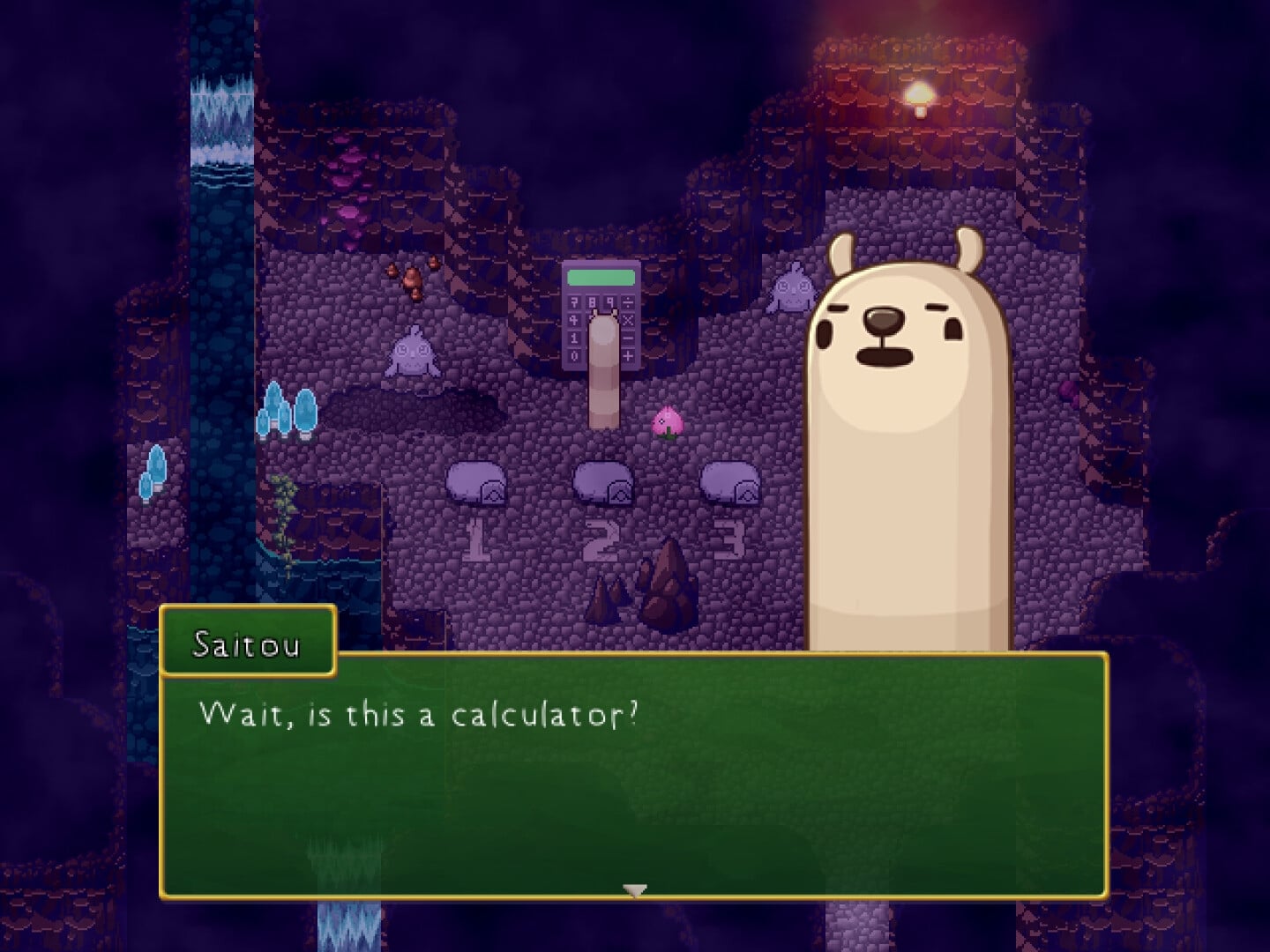

This process, as well as Shigihara’s cross-disciplinary approach, mean that the game always feels coherent. Gameplay springs neatly from central characters and themes, too. Bosstou likes golf, so there’s a sliding golf ball puzzle. Mr. Saitou has a minimori-phobia, so of course you have to collect minimori, as they migrate distastefully through everyone’s business. Mr. Saitou also eschews attention, so wearing the loudest possible disguise was always going to happen.

Puzzles are logical and straightforward, and I enjoyed being able to progress quickly through the game. It was also fun to solve puzzles, then meet their creator, who is honestly the goofiest-looking thing I have ever seen. A lot of questions I’d had about the ‘why’ of certain puzzles came together, in this moment.

The musical motif for the mori is similarly brilliant. Built (to my ear) on an unsettling flat nine interval, it really conveys Mr. Saitou’s disgust alongside the moris’ gormlessness. Also, depending on size, mini, mega or giga, when you put one on your head, you’ll get a correspondingly heavy beat layered on top of the mori theme. It’s another of the essential details that makes Mr. Saitou sometimes silly, sometimes serious, but always engaging.

Opposites attract

I once heard bittersweetness defined as ‘the acute awareness of the passing of time’. Every cute thing that happens in this game captures the attention of Mr. Saitou (and the player), even as he suffers quietly, which made me reflect on the value of living in the moment.

Shigihara says, ‘I really hope that players will take away the message that having a happy, full and meaningful life is so very related to how much a person loves.’

So, cast aside the day’s menial tasks and surround yourself with old friends, and new; cave buds, pungent onions, even a minimori or two. Laura Shigihara’s way of communicating complex emotions, while presenting so many more pieces of this beautiful world, is something to behold.

A demo for Mr. Saito is currently available on Steam.