A bug or a glitch in a video game is a manifestation of a fault within its design. It’s a mistake that game developers usually race to correct with an update of the game. And yet, “Any%” speedrunners see these errors as a boon, using them in order to finish a videogame in a fraction of the time it would take to play in a “glitchless” run. Clipping through walls and phasing into out of bounds areas allows the player to speed through a course or even skip entire levels.

Indie developers have also harnessed the glitch as an intentional part of game design, to provoke a visceral emotional response in players. A sudden crash of the program, corrupted text or disintegrating digital imagery immediately elicits the sinking feeling that something isn’t quite right. Games like Doki Doki Literature Club and Undertale used these strategies to not only instill horror, but to inject a personality into the video game itself: as though the game had a soul or a disturbed spirit. Ben Drowned, a creepypasta from 2010 which featured distorted and edited footage of The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask, and more recently, Petscop, a fictional Let’s Play series on a PS1 game that never existed, are unplayable (and perhaps, medium-breaking) versions of video game storytelling that have added to the horror of the glitch.

In many games of the Melbourne Queer Games Festival, it is exploited not simply as a source of terror, but as a positive disturbance of the field of identity.

2021’s Melbourne Queer Games Festival has a wealth of games exploring queer love, culture and experience from both local and international developers. In Winter, an interactive fiction work from Freya C and Elliot Herriman, you play a trans woman named Meredith who meets Winter, another trans woman who mysteriously doesn’t have a face: dark sockets instead of eyes, and white bone instead of flesh. This acts as a shield, revealing her insecurities about attraction and intimacy, while denying others the chance of deciphering her. At one point she confesses to Meredith, ‘I don’t know how to make myself feel vulnerable, or to tolerate someone’s eyes on me. What’s that phrase… the mortifying ordeal of being known?’

The story is accompanied with illustrations: some look as though they’ve been put through the noise filter on Photoshop over and over again, blitzed into shapes and brightly coloured dots. Others look like they have been scribbled with a mouse on MS Paint. Even the music is lo-fi: it has a buzz, a crackle. These images are beautiful and affecting nonetheless, and this pixel soup has the effect of obscuring appearance and rejecting clear-cut representation.

In In Defense of the Poor Image, Steyerl writes that poor images – that is, low-resolution images – are emancipatory, since they ‘express a condition of dematerialisation’. In other words, the poor image is free from the bonds of the physical: in digital, poorly processed form, visual representation is abstracted. It is evasive, not wholly tangible.

Other games in the Melbourne Queer Games Festival take this deliberate step towards a low-resolution aesthetic. Corfu Grapefruit Sun by gg noni plays like a hymn, a prayer for warmth and safety. ‘There is a difference between understanding and knowing’, the hymn says. Images are stretched beyond recognition (Is that border made of an image of salami or some kind of amoeba?), and gifs that appear to have been rescued from floppy discs flash and spin.

Fantasia Malware, the pseudonym for a collaboration between Gabriel Helfenstein, Jira Trello and Chloe Langford, create a sprawling plane of lore surrounding The Life of… Saint Fiona Bianco Xena, a patron saint for the motherless. It’s unclear if Saint Fiona Bianco Xena is truly a heavenly being or a normal woman made into myth by the Slug Farmer’s Union, but Fantasia Malware’s dynamic assemblage of high-definition twirling, jiggling bodies and pixellated, distorted chapel ceilings has me ready to leave a candle at her altar. It reminds me of the work of Hito Steyerl, film-maker, media theorist and video artist who also combines video games, overly-processed internet imagery and GIFs.

Steyerl’s work is worth mentioning here as she has contributed much to the critical discussion of contemporary digital culture, from the internet to video games. In In Defense of the Poor Image, Steyerl writes that poor images – that is, low-resolution images – are emancipatory, since they ‘express a condition of dematerialisation’. In other words, the poor image is free from the bonds of the physical: in digital, poorly processed form, visual representation is abstracted. It is evasive, not wholly tangible.

This is highly relevant not only to experiences of queer sexuality and gender in the games of the Melbourne Queer Games Festival but also to broader artistic interrogations of race and identity, like those of art curator Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism. As a Black, queer, and femme-identifying youth living in New York’s East Village, they felt a stranger in their neighbourhood as it became increasingly gentrified.

And so the glitch – ‘an error, a mistake, a failure to function’ – becomes a tool for empowerment.

They describe a disdain towards ‘the violence of this unconsented visibility’, where their character and identity was assumed and interpreted by their new white and wealthy neighbours. For Russell, the Internet appeared as a sanctuary where, separated from the prison of the body, these identities could for the first time be shifted under their own control allowing them to define how others perceived them: old, young, gendered, ungendered, powerful or powerless.

And so the glitch – ‘an error, a mistake, a failure to function’ – becomes a tool for empowerment. To glitch gender is to spurn its definition by the body and to refuse to perform gender. More generally, it is to completely destabilise what it means for a body and a name to be seen and understood by others, which ultimately comes down to binary, essentialising assumptions based on perceptions of race, gender and sexuality. Instead, glitch feminists occupy the real-virtual space of the digital and the online. They travel without borders and without a passport, identifying themselves via their avatar and username.

This defiance against the oppression of the physical comes to a head in Hua Chai’s userID, a point-and-click puzzle game, and boys curse/boys blessing by Nilson Carroll, an ‘anti-dating’ sim where you go on dates with the author’s various corpses. Your decisions in boys curse/boys blessing are binary: Do you choose the curse, which allows you to live out your identity without a label, but also without certainty? Or do you choose the blessing, a singular label that doesn’t begin to cover your complexity? There are four levels, and to enter each, you must choose a name by pushing letters into place. Milton? Or Nilson, Nielsen, Nelson? There can only be one.

This game is an energetic collage of badly photoshopped images, indiscernible thumbnails, and grainy flip phone photographs. In the game’s description, Carroll writes, ‘…when label and binary expectations are weaponized against me, when it becomes necessary to no longer be seen, and being named is too complicated. I recede into the gray sea of my dreams, but my bodily baggage floats behind me.’ The poor images in Carroll’s game aid in hampering this bodily baggage: the certainty that comes with labels and binary systems become impossible.

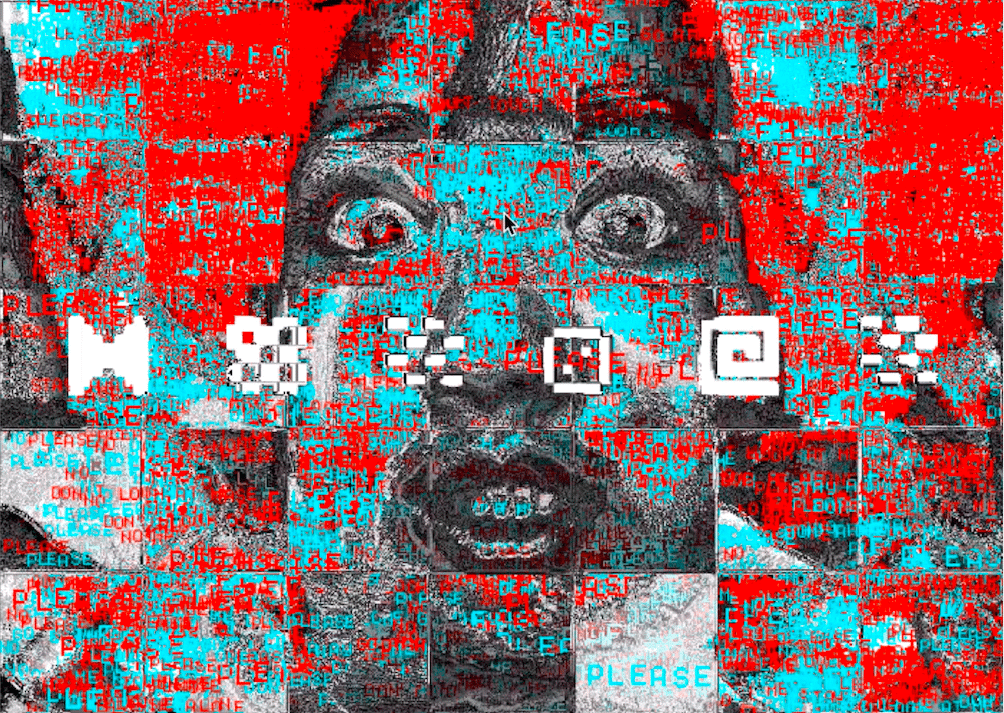

Opening up Hua Chai’s game, userID, you are greeted by a login screen. You’re a kind of hacker: guessing the password in order to see their profile and “know” this person. Instead of a profile photo, they have a GIF of an eye. Hovering over it jolts the game into violent defense: lights flash and in red text, it begs you to look away. Once you’ve put the password in, you sort through scrambled files and coded messages. Finding the eye within this rebellious grid allows the anonymous “userID” to speak to you. “What you seek are answers… impressions… codes… binaries…” As soon as you find this eye, the only discernible feature of the anon’s appearance, an error 404 pops up: the file no longer exists. ‘“You are looking for something to be known,’” they say. ‘“But right now what you seek still remains unknown – undefined in the language of binaries… Myself cannot be defined by binaries.’” The assault of visual and audible noise is a weapon against perception, and thus being interpreted by others. Hua Chai asserts that their self transcends the boundaries of the body and the binary. They are too powerful, too uninterpretable.

Queer game developers have transformed the glitch from a temporary, sudden optic and aural interference into a full-blown aesthetic. The glitch is a fissure, disturbing the visual plane and thus destabilising static categories of gender, race and sexuality, allowing fluidity and ephemerality. The glitch aesthetic consequently emerges as a means of deconstructing and reconstructing expression of identity: as something complex, multivalent, and in flux.

Claire Ming Osborn-Li is an art history student at the University of Melbourne. She writes about the ways in which contemporary art can learn from video games (of which there are many), and analyses video games from an art historical or theoretical lens.