I am a tiny lo-fi pixelated body, wandering through a virtual rendition of the Queensland University of Technology. I’m here to see a symposium on game-making, held by Brendan Keogh, a Lecturer in the School of Communication, and a Chief Investigator in the Digital Media Research Centre at QUT. I am plopped outside the main building, at a bus stop. Pale yellow dots dissipate into the sky: the sun is setting as my character walks to the entrance.

Sitting at my desk at home in front of a space heater, I am suddenly struck with a particular feeling of rushing into a building as the cold air of night closes in. Inside, I pick up a lanyard, which my character equips around their neck, before heading to the conference rooms: pixel art interpretations of QUT’s lecture rooms, with embedded videos of each talk filling up the projection screen. Heading out to the corridor, I wander some more. I am greeted by a barista who “serves” me virtual coffee, and a friendly pixel dog called Harry. I may be alone, but that doesn’t mean I don’t have company. Together, our 8-bit bodies take up space.

Now, I am visiting the Leopold Gallery in Vienna, except I didn’t come here by plane, but by mouse click. I begin smack bang in the middle of the exhibition space. It’s very pretty, but it’s also very smooth; I feel like I’m inside an architectural model. Already, any desire to explore has vanished: from the very beginning, I can see every corner of the exhibition in this open-plan space. An audio tour plays automatically as I enter each room, the sound travelling from ear to ear as I either use my mouse to click, zooming from position to position, or my keypad, which glides my POV across the floor, but turns jauntily.

On the walls, I can zoom into high definition scans of each painting and read pop-out labels. To look around, I click and pull my mouse, which feels sluggish, a sensation too similar to the pinching and dragging motions I make with my fingers while squinting at a photo on my phone.

Read: Gamifying grief: learning how to say goodbye through video games

Peering into the beyond through the skylight in the ceiling, there’s a flat expanse of white light, and I am reminded that I’m standing in a big box, floating in nothingness. The tour guide’s disembodied voice echoes through the enormous, desolate space, and I feel more alone than ever.

The white cube enters the digital realm

This virtual exhibition was one of many since the forced closure of art galleries and museums in 2020. In an attempt to translate the physical to the virtual, cultural institutions with money to spend and resources to flex during an already-dire economic climate moved their exhibitions online in 3D-rendered form.

Online exhibitions boast 360° vistas and AR and VR capabilities, but these panoramic photographs are empty and cold. The white cube, which already fosters a creepy, clinical feeling, becomes even more cavernous in virtual space, where galleries are devoid of human presence.

Taking the National Gallery of London’s virtual tour as an example — published in tandem with Google Street View — other issues arise, too. Movement through the gallery space is predestined. You cannot “walk” around a statue to view every angle: instead, you click on the floor, zooming from point to point, frames between photographs blurring and distorting.

As such, the camera stands a certain ways away from each painting. Zooming in to peer at it closer does not enhance its quality: instead, it becomes a rectangular blur. Labels are equally illegible. In virtual space, the gallery tour becomes not much more than a glance at the design of the room, akin to a 360° view of a property on a realtor’s website.

Another tour by the National Gallery uses Matterport, a 3D capturing system that aims to create a ‘digital twin’ of real spaces, boasts use in real estate, retail and insurance as well as in virtual exhibitions. The curiosity that would prompt me to explore a physical gallery space, to examine every object and read every label has vanished. Instead, I fly through an empty gallery, glancing at objects like a tired window shopper.

Galleries and museums appear to fetishise the high-tech, pursuing ‘immersion’ by replicating the physical reality as closely as possible. The visitor exists in these exhibitions as a floating camera, jaunting through a mansion filled with priceless objects.

Virtual exhibitions don’t need to replace gallery-going, and likely won’t. Seeing an object in an image doesn’t give us an accurate sense of its dimensions, or its texture. Without an understanding of embodiment in the virtual, these exhibitions fail to keep the sense of curiosity and discovery that drives the real-world desire to wander, examine details, read labels and ask questions. That governs exploration of digital spaces, like in video games.

‘Give me a body, god!’

Brendan Keogh gave word to my feelings of dissatisfaction with virtual exhibitions when he wrote about another virtual phenomenon to take hold during the pandemic: Zoom meetings. ‘Give me a body and spatiality and the ability to move in and out of conversations organically, god,’ he tweeted.

Trapped in video calls or a virtual gallery, it’s all the same: where is the sense of embodiment? Where is the spatiality and movement? So when it came to hosting a symposium on Australian game development skills, Keogh wanted to create a democratic space for free-flowing discussions and diverse presentations that weren’t possible on a Zoom call.

He found his answer in the Freeplay ZONE.

Developed by programmer and game designer Jae Stuart and digital artist Cécile Richard, the virtual Freeplay event in 2020 was based on LIKELIKE’s Online Museum of Multiplayer Art, whose code was made open-source by its designer Paolo Pedercini. Keogh commissioned them to create the Workshop Zone, a pixelated adaptation of the QUT campus, complete with conference rooms, an exhibition space, and virtual catering (here, meaning unable to be actually eaten).

Embodiment and spatiality in games

In 2018, Keogh published A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames, examining the unique hybrid embodiment of the video game medium: ‘[It’s] not just simply leaving one body behind to pick up another body,’ Keogh says. ‘If I’m wearing a virtual reality headset, I can still get motion sickness, I can still run into a wall. Right now I’m looking at my Zone on the other screen, but I can still see my Chrome shortcuts and the time and my noticeboard behind that — that never goes away. So videogame embodiment is a hybrid embodiment of the actual and the virtual … You always kind of mash together.’

If embodiment is the way in which we understand the world, then embracing this hybrid body, what Keogh calls the ‘cyborg’, is our means of communicating with the virtual. For virtual exhibitions, this means allowing for the presence of a body.

When institutions use programs like Google Street View and Matterport, our only means of meshing with the virtual world is via the visual: as though looking through a drone. With a body, which we can control and move around in relation to that space, we have a sense of our own relation to that space, even as we thumb arrows on a keyboard or squint at a bright computer screen.

Embodiment also produces spatiality, but as the Zone demonstrates, it can be reinforced by other elements, too.

Upon entering The Workshop Zone, participants choose an avatar, land on a street, and click to move. They can also type in the chat to talk to others. For Stuart and Richard, seeing a body arrive at an “outside” and having to enter into a building produced spatiality: a sense of destination and ‘being somewhere.’

In the original Freeplay ZONE, the effectiveness of the spatiality fostered by this outside/inside design manifested when the event began to wind down: players went “outside” and stood on the pixelated pavement bidding goodbye, marking the return to their “real lives”. In lockdown, the need to recreate this feeling is even more salient, as Cécile Richard says, ‘[It’s about the] underlying idea of “I’m here right now” and I feel that’s a very powerful statement to bring about … to me it is important to feel like you are somewhere, when you’ve just been in your home the entire time.’

While corporality and spatiality are the main building blocks of ‘being somewhere’, the developers made efforts to fold in what Richard calls the ‘little details.’ A warm fire in the Zone’s “backyard” was one example, which created that familiar feeling of heading outside of a bustling party for a quiet moment, and being hit by the brisk night air.

Designing the virtual

The Workshop Zone included an exhibition to display Keogh’s 200-odd interviews with game developers organised by the themes that arose during these interviews: on why they make games, what it is to work in the industry and be in the community, and where it’s all heading.

Walls divide the room and funnel the player through the space in the correct sequence. Monitors hang on the wall here and there, and selecting these pop-up a window to play a game. Wall text is displayed in pixel-form — illegible in the space itself, but clicking on each brings up the text in full.

The elements of this exhibition space are very simple, and yet very intentionally designed for the digital space. Colours are fun and citrusy, which may have been too bright and distracting in a real space with real objects. In the virtual, however, they provide a welcome backdrop for the dark boxes of text. In contrast, major institutions produced virtual exhibitions that felt almost unintentional: accidental products of the software they had poured money into.

When I wander through these rooms alone, it is months since the symposium took place. At the time, you could stop and talk to others about their thoughts on the lectures delivered, as well as the interviews and games featured in the exhibition.

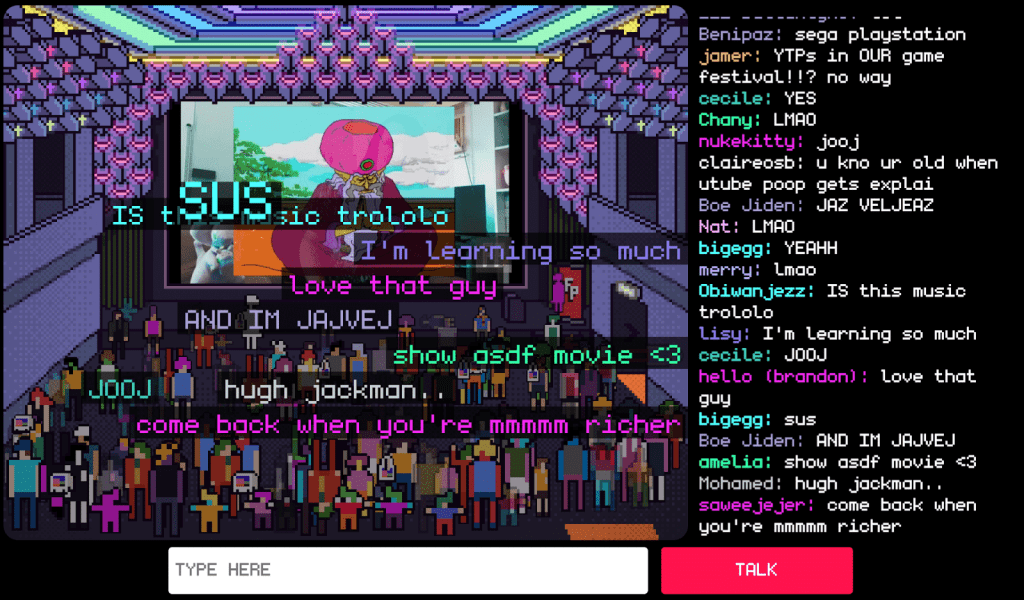

Attending Freeplay’s 2021 Parallels event, I witnessed these kinds of moments ‘in person’. As the night’s talks played on a YouTube embed, which appeared in a virtual adaptation of RMIT University’s Capitol Theatre, our technicolour bodies stood close.

Speech bubbles appeared over the crowd as we cheered, we LOL’d, and we cried. We expressed thanks loudly to the deliverers of the pre-recorded speeches, and typed “/honk” to imitate the popular Untitled Goose Game honk noise.

Gallery spaces are social spaces

What if art galleries and museums had remembered that visiting an exhibition was not only about seeing dinosaur fossils or an Impressionist painting, but were often explicitly social acts?

You bring a friend with you to the gallery and point out details to each other, grabbing a coffee afterwards to go over the highlights and critique the pitfalls. You visit the museum with your family, running from exhibit to exhibit — or maybe you go by yourself, and talk to a staff member or tour guide.

As Cécile Richard put it: ‘It’s not just about being someone somewhere, but it’s your being someone somewhere with other people. And I think that makes the entire difference.’ They see their role not only as a digital artist, designing the function and aesthetic of the space, but also as someone who is fostering community. This impulse can be seen in their game design work too, which explores themes of connection and reminiscing.

I do not suggest that galleries and museums should now make all their exhibitions in pixelated, third-person form. Some works, such as sculpture, must be viewed in three dimensions. But as Richard points out, ‘being somewhere and embodying a person or occupying space is more than immersion.’

Simulating the view of a camera transporting from one spot to the next creates the sense that I’m a disembodied head, not a viewer with a body and a presence. Reproduced over and over in the same 3D, first-person, Google Street View-style, institutions are giving into the same kind of attitude that Keogh calls ‘the technological arms race way’ of thinking about the virtual, where the goal is to mimic real life as much as possible, rather than to interrogate the way in which embodiment and spatiality are shaped in virtual spaces.

Part of the success of the Zone is that its creators understood that the virtual space had limitations, and embraced it. Instead of aiming for an imperfect and uncanny immersion, they veered towards the approximation of pixels.

Keogh underpinned this in our disembodied, de-spatialised virtual interview: ‘The Zone really proves that it doesn’t need photorealistic 3D graphics, it doesn’t need complicated ways of moving around a 3D world, which requires two thumb sticks and 14 buttons: all you need is something that is understandable as a space and something that is understandable as a body, and a way to move that body through that space.’

This piece was commissioned as part of the 2021 Wordplay games writing mentorship program, a partnership between GamesHub and Melbourne International Games Week. Special thanks to mentors Jini Maxwell, Dan Golding, Rae Johnson, Brendan Keogh, Alice Clarke, and Edmond Tran.

Player-Favourite Gambling Guides

We’ve handpicked our latest and most visited guides covering online casinos, betting sites, and more—for every kind of player.