Much like the titular aircraft that rocket across the surfaces of its far-flung intergalactic world, the leadup to the launch of 2021’s JETT: The Far Shore had a long tail. In conversation with co-creators Patrick McAllister and Craig D. Adams – prior to the launch of game expansion, Given Time – the developers spoke of the game’s almost ten year development cycle; the fruit of which was JETT’s wildly ambitious and divisive blend of intergalactic drama, flight simulation and religious parable.

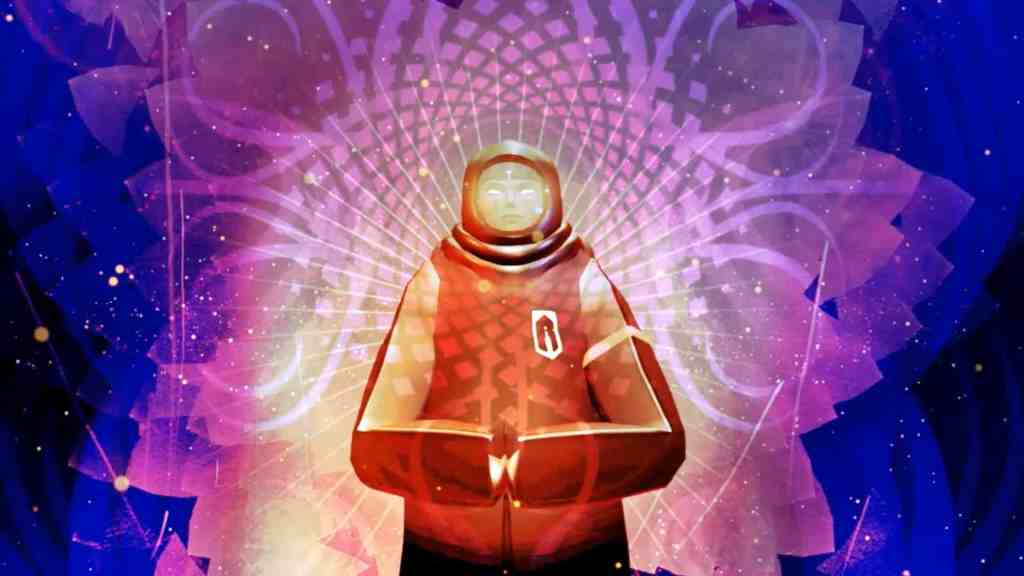

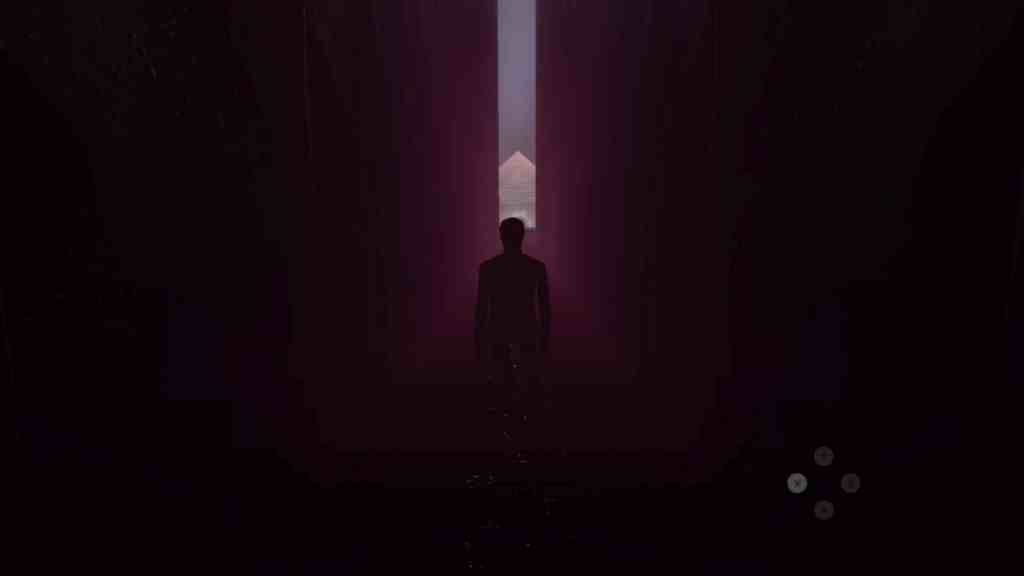

In JETT: The Far Shore, players control Mei, a member of a select group of intergalactic travellers who leave their home planet in search of a new home, and the origins of a mysterious, long-distance radio signal that was foretold in their culture’s religion. Once they’re afoot of their new home planet, players must fly specialised aircraft to study the local environment and survive in its new, bizarre ecology.

Read: Jett: The Far Shore Review – Confronting the Future

From speaking to McAllister and Adams, Given Time sounds like it doubled as a kind of cumulative reset for the headspace the two had been working under for so much of JETT’s development, allowing them to truly roam free of the ideas and expectations they’d placed upon themselves during the crafting of the base game.

As Adams tells me: ‘It felt like Patrick and I… we had to learn a lot over the course of this project, and I felt like in 2022 (during the development of Given Time) we could see the benefit of that learning. Actually delivering Given Time is a really special thing, and it felt really good to get it through to the other end and in a way we’re proud of.’

Reshaping the base parts of JETT was always on the agenda, and the team returned to the fundamentals of this ‘strange snowboarding game’ – as Adams describes it – to see a path to closing out the experience as a whole.

‘The material that makes up Given Time is kind of the core of the gameplay that we had in mind in the sense of it being, you know, a little more free roaming and player-driven and more about ‘how do we get these ecosystems and puzzles and light survival’ to intersect,’ says Adams.

In a strange way, the time spent on Given Time during JETT’s original development ended up providing the mechanical staging ground for the majority of the systems that would appear in the base game. Adams explains that through the struggles of development, the team found it made more sense to ‘decouple’ Given Time from the other chapters of JETT. ‘Which was not the worst thing in the world in some ways,’ Adams says, ‘because we’ve already designed the story so that it has this three-year interval and this reset moment, so that’s a cool reveal of a sort of semi-sequel.’

On reflection, Adams found Given Time’s delayed release heightened the effectiveness of the storytelling, and where the game picks up after the Far Shore campaign.

‘As usual, the scope increased a little bit in some places,’ chuckles McAllister, somewhat sheepishly, ‘but it’s all the better for it, I think, and we were able to make good decisions and not go too crazy, but still bolster the parts that would really resonate with folks.’

‘In a weird way, it’s kind of perfect that we had the cake [Given Time] mostly baked,’ says Adams ‘but we could put it on the shelf; Far Shore goes out, take a deep breath, refresh, get limbered up and then go back in and be more able to round it out and get it to take up the space that it felt like it wanted to, and do justice to that.’

Speaking frankly about the development of JETT: The Far Shore and Given Time with Adams and McAllister brings up a lot of similar ideas, both logistical and emotional; there’s a lot of talk of learning, timing, and the emotional pull towards a finished vision of the JETT project, one that had characterised so much of their lives. So, a year and some on from JETT: The Far Shore’s original launch, is this finally the package Adams and McAllister had always envisioned?

‘It does feel like it is the complete vision. Like if I go way back, does it match exactly what was in our heads? Maybe, probably; but at this point we went further than we would have imagined back in 2013,’ says Adams. ‘Certainly, you know, anybody who’s played it will have a couple of notes about it, and if they traverse Given Time they’ll find the gameplay potential, and they’ll also find some story closure which we intentionally didn’t provide in The Far Shore.‘

In a conversation with Game Developer in the weeks after the launch of JETT: The Far Shore, Adams spoke candidly about the development of the game; wrangling the scope and turning it into a cohesive experience, saying that it takes about ’10 hours to fall in love with the game, but only 10 to 15 hours to complete it’. When I recount the quote to Adams and McAllister they laugh, like being reminded of some old inside joke. ‘Maybe I could have approached that a little differently,’ mumbles Adams, chuckling. ‘I appreciate that quote as well,’ says McAllister, ‘but I think it also points to our approach to developing it as a whole… like, maybe yeah the flight model is probably overdevelopment or tuned in a way that is very deep and rich, but you can explore it and continue to learn it over time.’

That focus on creating something that was truly three-dimensional, interesting, and unique cannot be understated as a risk of game design, to the point where, as McAllister puts it, the ability for the majority of players to appreciate it would be put at risk. ‘It was slightly secondary, and that’s where a lot of the struggles are. Like we have this relatively deep, rich thing, and we were always pushing ourselves to try to make it more and more comprehensible and immediately graspable.’

As production on the base game wound down in 2021, the team brought on Randy Smith, notable for his history with the Thief and Might and Magic franchises, and well-versed in games thick with systems that require a lot of player understanding.

‘He’d been right in there with Zach [Wheeler] – who was kind of Randy’s design understudy through the Far Shore, and they’d been right there in the trenches taking the kind of floppy mechanics and entities and locations that Patrick and I had mocked up,’ recounts Adams, ‘and they dug in and put everything through its paces and tightened up all the screws.’

After Smith’s time on the development team, he produced a comprehensive report which saw him play through all the existing content and give letter grades for each aspect of JETT, guiding the team on where to go next after his departure; an invaluable document during the 2022 development of Given Time.

Even from the outside, the development of JETT: The Far Shore and Given Time seems like an ultimate crash course in the balancing of the fundamentals that knit together so much modern game design. Ambition, expectation, understanding, familiarity, and surprise. And JETT is an example that success and failure can exist alongside each other within a single project in the most unique of ways, sometimes combining to create something truly unexpected and singular.

Viewing the game’s systems as pieces of a product can miss how they mirror the unwieldy, weird, and ambiguous nature of the game’s narrative and themes, however. Looking at the finished product, it’s almost impossible to view them as anything other than perfectly of a piece with each other.

Adams concurs; ‘this thing ended up being this kind of moon shot for us, like, can we pull it off? The allergy to convention that helped make [Sword & Sworcery EP] distinct in some ways also helps make JETT distinct, but having disruptive, innovative, nonconventional decisions across so many axes – stacking things and making things strange – you’re further and further away from a map or easy references, and it adds to development time and it’s taxing for a player. That’s one thing I would take to a next project.’

‘One of the biggest things is how allergic to conventions I feel like Craig and I were at the beginning of the project, and I’m a long-time PC gamer,’ McAllister tells me, as he recounts what’d he’d describe as his most important lessons from the years spent on JETT: The Far Shore.

‘I like stuff that is a little opaque. We both [Adams and McAllister] love turning the HUD off and things like Shadow of the Colossus. To a degree that’s the heart of what we wanted, to really ground stuff and not use gaming tropes as shortcuts. It turns out that when you make a game like that, the players don’t know anything, unless you’re really skilled at what you’re doing, and we did our best, but I think we didn’t have the chops necessary to deliver on a perfectly understandable game. Conventions exist for a reason, for sure, and you can challenge them, but it’ll take a lot more sweat and tears to actually get things to the finish line.’

The timelines being thrown around by Adams and McAllister really strike me.

This project has been one that has defined an entire decade of their lives, mostly to the exclusion of all others; how does it feel to be at the end?

‘I don’t want to work on a project this long again,’ laughs McAllister, ‘we did well…it’s so exciting to be able to start looking abroad.’ Adams is more circumspect; ‘great…it feels really great. The satisfaction of delivering the vision, and having it gone relatively well, and seeing some early positive responses – that feels great.’