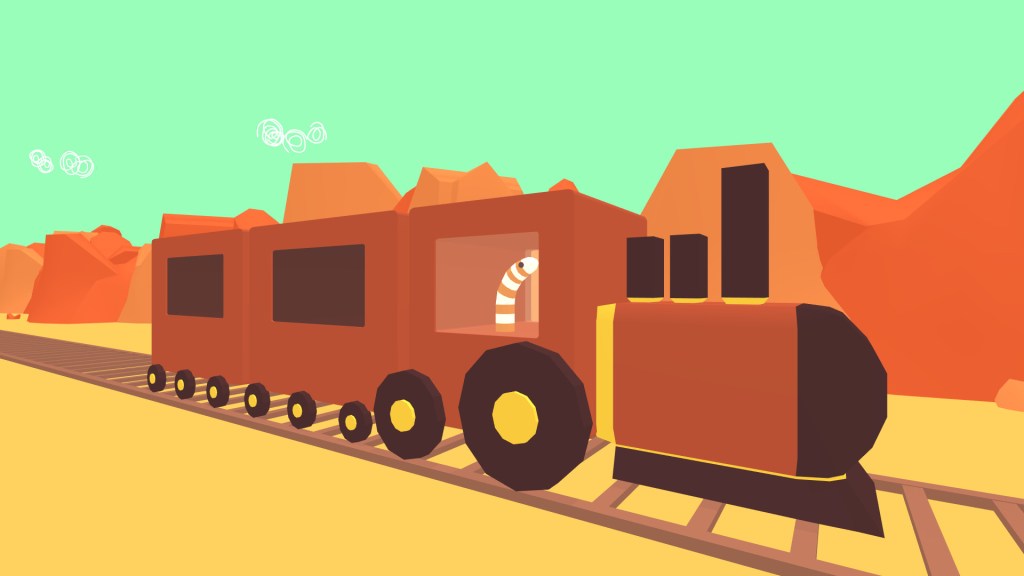

For the past four years, the unique wit and humour of the Frog Detective series has helped define the face of Australian indie games. With an absurdist sense of humour that is brought to life by studio Worm Club’s Creative Director Grace Bruxner’s idiosyncratic character designs, these small, lighthearted narrative games have offered another perspective on the conversation about videogames as an art form: they show that ‘culturally meaningful’ and ‘extremely silly and fun’ aren’t so antithetical after all.

[Note: This article was originally published on 22 July 2021, and has been reposted to mark the release of Frog Detective 3.]

In July 2021, the studio announced that the anticipated third game in the series, Frog Detective 3: Corruption at Cowboy County would be released later in the year. With this exciting news comes the bittersweet note that this game will complete the trilogy.

It’s a defining moment for Worm Club, whose first commercial game release was 2018’s The Haunted Island, a Frog Detective Mystery. An instant indie darling, The Haunted Island was selected to show at Day of the Devs at GDC, won the title of Most Fantastic at Fantastic Arcade 2018, and was even nominated for Best Student Game at the 2018 IGF Awards. It’s a remarkable set of props for a game that was primarily developed while Bruxner was still undertaking a game design undergraduate degree.

Read: The biggest Australian-made games coming in 2022-23

Over the years, these wins have solidified into something sustainable: Worm Club, which Bruxner co-runs with Design Director Thomas Bowker, was the first studio to sign with publishing label SUPERHOT PRESENTS, who publish Frog Detective 2 and 3. They have also been able to work full time since The Haunted Island’s release, bringing on Untitled Goose Game’s Dan Golding to develop noir-inspired OSTs for each entry in the series, and currently employing Surf Club’s Olivia Haines to do extra 3D modelling for the third instalment.

It’s not the end for Frog Detective: Bruxner plans to pitch it as an animated TV show, and she’s excited about the other formats Frog Detective stories could take. But for this game trilogy, it’s time to move on.

We spoke to Grace Bruxner about how it feels to move on from the amphibian sleuth who made her career:

You started developing Frog Detective in your final year of university, and you’ve been working full time on the series since then. Was closing the door on Frog Detective a difficult decision, or did the team arrive at it relatively naturally?

I don’t view it as closing the door, because I think Frog Detective as a concept can exist beyond three small games. Once we’ve finished development, I want to work on pitching it as an animated TV show. I think one struggle with Frog Detective as a game is that our resources are limited so getting the games out takes a long time and a lot of effort. I love it more than anything, but I also think there’s so much potential for a lot of small FD stories to be told in another format. It’s by far the most ambitious creative leap I’ve aimed for, and I am very prepared to fail spectacularly, but why not try?

I treated [The Haunted Island] as a success before it was one, and it became successful over time. I’m glad I was naive enough to do that.

Grace Bruxner

The door isn’t closed on Frog Detective as a game series, necessarily, but this chapter is the last one in this arc. It’s important to me that the things I create have a planned end, because it allows for richer storytelling in my opinion. In terms of deciding when to end the arc, I don’t have a clear memory as to why we chose to do that. I think partially it was because when we pitched the series to SUPERHOT, they signed on for 2 games and we went into development with the mentality that we would only be surviving financially for 3 games in total. Obviously, things have changed a lot since we pitched, but we’d planned the story quite far in advance and didn’t foresee the success of the game to this scale.

I think 2020 was the year that things really started to ramp up, and we were already in production of FD3 by then so we didn’t think about it too much. It’s also a really significant amount of work to make a Frog Detective game, and we really want a break before we continue with any new (or existing) projects. Let Worm Club Have A Holiday 2022.

You have a very committed fanbase, but it must still feel a bit nerve-wracking to move on from the series that has established you as a commercial gamemaker. How do you feel about the transition into new territory, for the studio overall and for you personally?

Maybe once development is finished some of that panic will set in, but for now, I feel pretty relaxed about it. It could be arrogance, but I have a fair amount of confidence that people who like Frog Detective will enjoy whatever I make next. Frog Detective encapsulates so much of what I enjoy about games and storytelling, so I hopefully can recreate that joy in another project. It’s so exciting to think about what a new game could be.

If I make Frog Detective forever, the world will never see the next thing I come up with. Electric Eel Park Ranger, or something. Hitman 4. I dunno.

If I make Frog Detective forever, the world will never see the next thing I come up with. Electric Eel Park Ranger, or something. Hitman 4. I dunno.

Grace Bruxner

Your approach to building Frog Detective’s audience and profile seemed very organic and social — tweeting (successfully!) at Limmy to stream Frog Detective is a recent example, but you’ve also streamed with Giant Bomb a few times, and you’ve amassed a pretty enthusiastic fan base on Twitter who seem just as much fans of you, and your sense of humour, as they are of Frog Detective. Looking back, how do you feel about the fact that over the course of making and releasing these games, you’ve become something of a public figure?

Actually I only ever subtweeted Limmy! I would never wish to bother him with my tweets. It was his fans that tagged him and got him to play. It was very alarming to be watching a Powerwashing Simulator stream late one night and hear him mention Frog Detective out of nowhere.

I don’t know how to word this without sounding like the most pretentious person alive, but I think there are three versions of me. I think this is the case for everyone, but sometimes it feels very amplified for me because of the public nature of it. There’s the online/Twitter version, which is a nonsensical approximation of my personality. She does not exist, but occasionally a sincere thought will slip through the cracks. Then there’s the professional game developer version, which exists in conference talks, business meetings, emails, interviews etc. This version is the hardest to be. I know what I’m doing to an extent, but I am very regularly out of my depth.

I don’t want to be the real version of myself online because the real me is kind of a dumbass.

Grace Bruxner

Also being a “professional” in this sense feels like I am no longer part of the fun cool art developer club, which was fun to be in. Let me back in!! Anyway, the third version is the real me, Miley/Hannah style.

Separating the public image of myself from my actual self is the reason I have been able to mostly stay sane. I know that I am not the prodigy/genius that some (extremely kind) people think I am, and having that separation means I can make mistakes, learn, and grow privately around people who know me more realistically. I don’t want to be the real version of myself online because the real me is kind of a dumbass.

Following on from that: do you feel pressure to be ‘Grace Bruxner who makes Frog Detective’ all the time?

I don’t, because I am Grace Bruxner who makes Frog Detective. The games are a real representation of what I want to create, so representing them as myself comes naturally. Maybe with some time and distance I’ll feel differently, but I don’t have the sensation that I am forced to act as someone I’m not.

The only part that bothers me is the perception that I am the only person who makes Frog Detective. Creatively it’s very much my baby, but my partner Thomas Bowker does so much work and the games would not exist without him. I am not a solo developer, it’s a myth!

Having your first commercial game become the critical and commercial success that The Haunted Island was is a huge achievement, and one that has obviously shaped the past three years of your life. Do you ever wonder what the last few years of your creative life might have looked like if The Haunted Island had done fine, but maybe not made such an impact?

I had to think about this question for a while. The truth is that The Haunted Island did actually only do fine, and didn’t make a huge impact when it was released. Frog Detective was never about money or success, I just wanted to make a silly series. I can’t remember how many copies we sold in the first couple of months, but it wasn’t a huge amount. I really believed in the game and loved it, so I was going to make a sequel whether people wanted me to or not. It’s not quite “fake it til you make it”, but I treated the game as a success before it was one, and it became successful over time. I’m glad I was naive enough to do that.

If I went back in time and all my pushing and promotion didn’t work, I would have done what every indie does and try again. And if that didn’t work out for me I would work at the post office being the stamp licker.

Grace Bruxner

Making games commercially is really hard! If I went back in time and all my pushing and promotion didn’t work, I would have done what every indie does and try again. And if that didn’t work out for me I would work at the post office being the stamp licker. And then 2020 would roll around and I’d be made redundant because of the coronavirus germ risks that come with stamp licking.

Before Worm Club, you held a QA role at League of Geeks — could you have seen yourself working in a larger studio, or do you think starting your own studio was always going to be the right path for you?

Firstly, massive shoutout to League of Geeks. They took me on very early into my career and supported me beyond what any company needed to. I will forever be grateful for that. In terms of career progression, I quite seriously never thought about it. For my first year at RMIT I was sure that I wasn’t going to get a job in the industry, let alone make my own studio. When I started working at LoG I began to think that maybe it was possible. I was moving way too fast to stop and think about the future. Really, I just wanted to make the frog game and see what happened.

Leaving LoG was a very big decision and I did it without much career security, but I was 21 and didn’t care much for thinking ahead. I still don’t. To answer the original question, I guess I could have worked in a larger studio, but that wasn’t something I thought was realistic to think about.

Something I find really remarkable about your work is your approach to the business side of game development. Worm Club was the first studio to sign with SUPERHOT PRESENTS, quickly followed by fellow Australian Andrew Brophy, and you’ve given some fantastic talks about Worm Club’s approach to bizdev. You’ve also consulted with WINGS, an investment fund that supports game dev teams with diverse leadership, on top of being Worm Club’s Creative Director. This is such a rare and valuable skill set in the indie games scene — can you imagine yourself doing more of this kind of consulting or contract work in future, or are you keen to focus on Worm Club exclusively?

It’s very important to me that other people have access to the opportunities that we’ve had. Consulting makes it sound more official than it is, but I try to connect developers to investors and funding where possible. Talking about money and business can be uncomfortable, and when you start to make money in games it’s almost impossible to avoid losing touch with reality, so remaining sensitive to other peoples’ financial situations is something that I haven’t always succeeded at.

That being said, I find myself constantly frustrated by the amount of talent and amazing games being made that don’t have access to the same things that we do. And part of bridging that gap is having candid conversations about money, even when it feels gross.

The reality is that there is so much funding at the moment being distributed by platforms and orgs that is only being given to people who know where to look. I only know where to look because I’ve had people who told me where to look and who to talk to. If I can be that person for someone else I will. I have definitely considered consulting professionally, but for now, I’m happy to give that info away for free, to the people who need it.