This year marked two very special anniversaries for the Australian games scene: ten years of the government-backed Melbourne International Games Week, and, incredibly, 20 years of the Freeplay Independent Games Festival.

Freeplay was founded by then Melbourne House developer Katharine Neil in collaboration with Marcus Westbury, who at the time was directing the long-running This Is Not Art festival. The first real indie games festival of its kind anywhere in the world, Freeplay met with such overwhelming success in 2004 that the pair brought it back again in 2005.

Freeplay has had a heck of a ride since then, enduring six different leaderships, multiple changes in local government, evolving societal optics for video games as a medium, and several seismic shifts in the game development landscape both locally and abroad.

We caught up with Katharine Neil a couple of weeks ahead of MIGW, where the beloved Freeplay spin-off Parallels showcase is set to also celebrate its 10 year anniversary.

Read: Freeplay: Parallels 2024 – Everything we learned

“Trying to get that project off the ground made me realize that there was a problem, well obviously aside from the problem that made me want to do that project,” Neil tells me via video call from her home in Saint-Denis. “There wasn’t really an indie game scene to speak of. There was no cultural visibility for games that weren’t seen as completely commercial even within the games industry. It was a very minority position that games could be culturally interesting, important, or even vaguely artistic in any way.”

“There was anti-intellectualism within the game industry but also a huge amount of cultural prejudice against video games and the people who made them in fine art circles. There was also no such thing as a games degree, and without institutional paths and homes for games development it’s very hard for people from marginalized communities to establish themselves. So from all directions I had this big chip on my shoulder.”

The rebellious origins of Freeplay

“I had colleagues at the time who were creatively frustrated as well because of the game business and the market,” Neil continues. “We all wanted to do cool shit, we just couldn’t. I was involved politically with the Refugee Action Collective Victoria and was trying to mount Escape From Woomera. I had colleagues and friends who wanted to do the project with me. I tried to get funding, because in those days you had to pay tens of thousands of dollars to license game engines … I got pushed back from CineMedia, (VicScreen’s predecessor), and told ‘well we don’t fund video games, we fund digital media art.’ I was like, ‘tell me what the difference is?!”

For those unfamiliar, Escape From Woomera was a game Neil conceived of and worked on with a small team of Australian developers. In it, you play as an Iranian refugee to Australia, locked up in the now-shuttered Woomera Immigration Reception and Processing Centre.

The facility was opened in 1999 by the Howard government specifically to detain unauthorised asylum seekers and received an immense degree of protestation from global human rights groups as well as from a segment of the Australian public throughout its four years of operation.

“Trying to gather support for Woomera made me go out into the arts scene for help … I saw that the This Is Not Art festival up in Newcastle had a sub-festival called ElectroFringe,” Neil continues. “My secret ambition was to contact Marcus Westbury, the festival’s founder, and go ‘could we do an independent games thing at This Is Not Art?’ He was a big cheese though, and I was nobody.

“In 2003 we got the (government) funding (for Woomera), then there was the big media scandal about it, which Marcus happened to notice. He reached out to me and said he was now in charge of the Next Wave Festival in Melbourne, and that he wanted Escape From Woomera to be somehow involved in it. I said ‘what about a half day for independent game projects in general?’ He said ‘screw that, what about three days?’”

While Neil knew that a lot of hobbyist game developers were out there, they were a lot less visible than they are today. While Neil and Westbury were confident that Freeplay would succeed, they had no real way to gauge just how enthusiastic the response would be.

“There wasn’t really a coherent community. I went out and tried to find the little online demographics that would be interested,” Neil tells me. “It turned out that there was a massive appetite for it! I think that Freeplay effectively served to give the community a sort of identity. The term ‘indie games’ didn’t really exist as such.”

“I was organizing all of this anonymously because my job contract (at Melbourne House) was very strict,” Neil adds. “I used the fake name ‘Kipper’ for years, even at the first and second Freeplay. I couldn’t really be visible as my name. I couldn’t put my name on anything. Our bosses were not very happy about Freeplay. They saw it as a rebellion.”

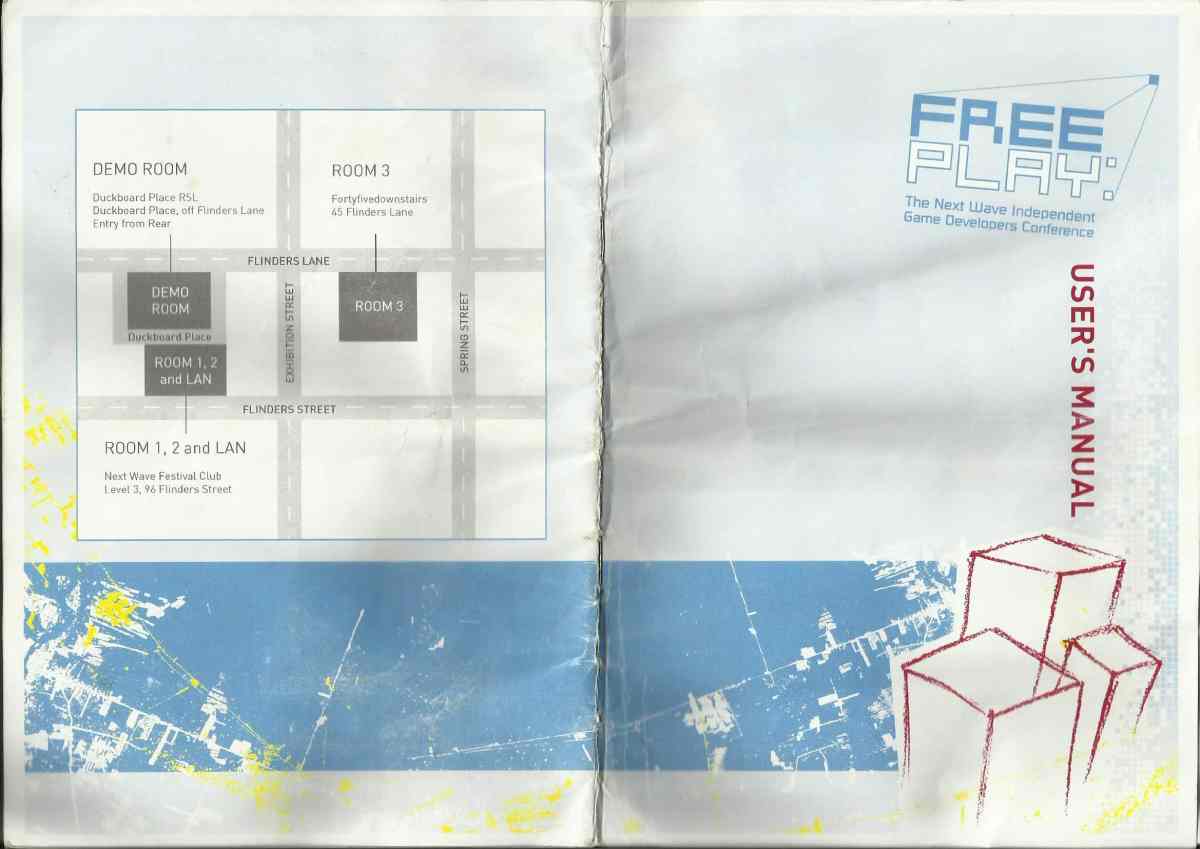

“The tickets sold out on the morning of the first day,” Neil continues with a smile. “We had this karate club with a bar inside and a couple of other venues in Flinders Lane. There were people queuing up outside before we officially opened, saying, ‘I don’t have a ticket, but can I still get in?’, so we started assigning people as volunteers. I think it was 350 tickets sold, and that was capacity.”

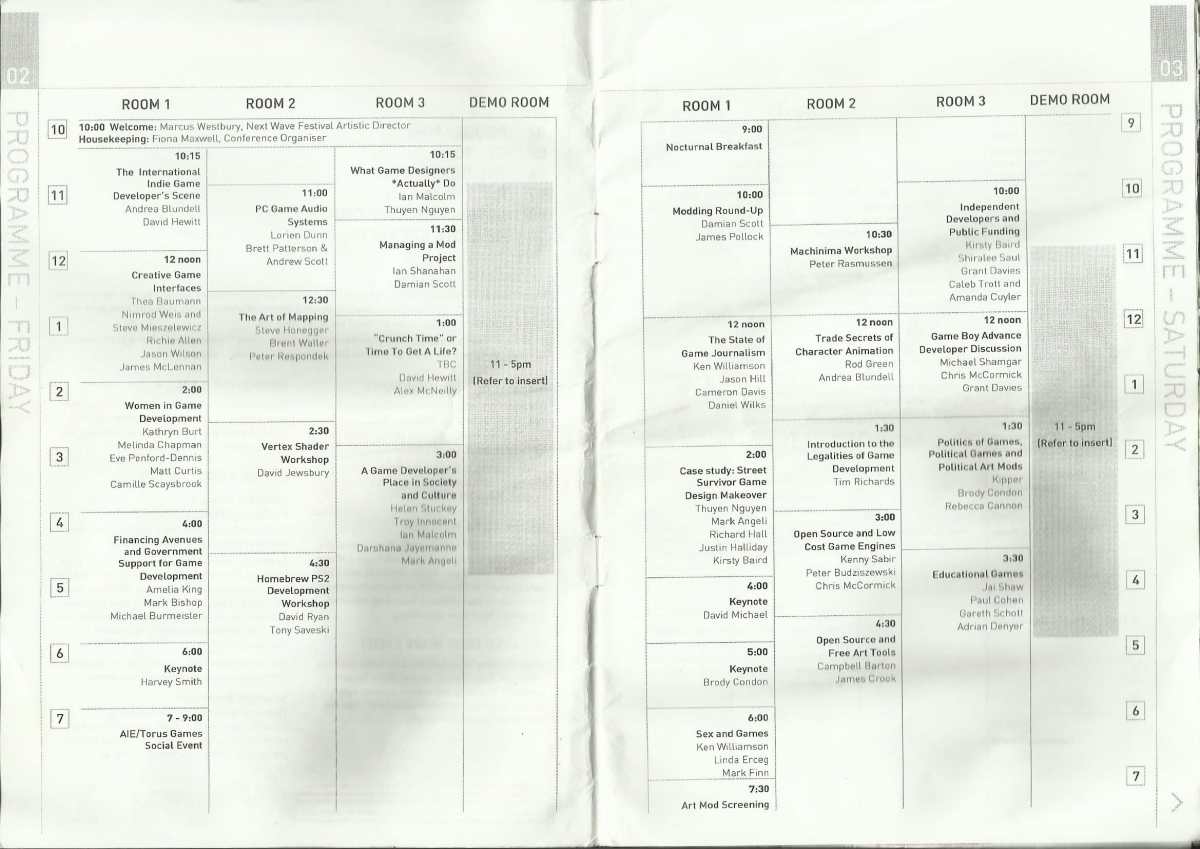

Frustratingly little evidence that the 2004 festival even happened exists online. Over the years, Freeplay has grown to have a consistently staffed board that oversees its stewardship, but sadly even they don’t have photos from those first two years in their archive. Included in this feature is what little Katharine herself was able to graciously provide us, including a scan of the 2004 programme.

“We had money for international speakers because of Marcus and Next Wave,” Neil says appreciatively. “We got Harvey Smith from the game development community. We had Brody Condon from the game art community. We had mappers and modders who ran workshops. There were very technical workshops on writing pixel shaders and stuff. We had debates about games media.”

“We had someone showing their digital media art, which was like soft porn,” Neil laughs. “That shocked some of the more conservative dudebros.”

A week earlier I’d chatted with Mads Mackenzie and Louie Roots, who took administration of Freeplay under the board in 2023. Knowing that I was going to be chatting with Neil soon, Mackenzie had one question for me to pass along: Did she have any idea that what she created would carry a 20 year legacy?

“When you’re that age, you don’t imagine things 20 years later,” Neil says nostalgically. “Freeplay has been through so many hands, it was just kind of lucky that people picked it up and kept going with it. I was involved for the first two years and then I moved to France. Eve Penford and Paul Callaghan picked it up after it had been sitting on hold for a couple of years, (there was no festival in 2006), and decided to get the ball rolling again.”

“It got a board. It went off in a direction I personally wouldn’t have taken it in, but it’s for the people who are doing the work to take it wherever, right? We did this thing for two years, so I don’t want to get the credit for something that other people have done,” she laughs. “I just think it was lucky that it worked out and ended up continuing. People could have just called it something else. It’s a really awesome feeling to have that thread continuing in a very different scene. The community has very different needs now, but the bastards are still out there screwing us over.”

“Freeplay was a political act in some ways, you know?” Neil continues. “From me and my colleagues’ points of view, there was the workers’ rights angle, but there was also the cultural one. Why I wanted it so much was because projects like Escape From Woomera couldn’t get support without having some cultural visibility. Freeplay showed that there is something called ‘indie game development’, and artistic game development. We’re here, and you should fucking support us. We’re an important part of culture, and this is our voice.”

Freeplay’s Parallels ‘24 was held at the Melbourne Town Hall on 10 October as part of Melbourne International Games Week. This article was commissioned by GamesHub with support from Creative Victoria.