For decades, First Nations peoples have been asked to tell their stories across media, sharing established wisdom, knowledge, culture, and experiences in film, television, and even video games. But as creatives Ben Armstrong and Brooke Collard discussed at GCAP 2024, sharing these stories means nothing without First Nations folks having agency over them.

“When I’m thinking about story agency, it isn’t just the fact [that] you get to create something, that you get to express yourself or get a message across. It goes back to wellbeing,” Collard explained. “It’s really important, not just for accurate representation and making sure that people are seeing themselves reflected in screens and games media of all forms. It’s about that healing process.”

Without agency, representation can feel empty and inauthentic.

In the telling of First Nations stories, both Collard and Armstrong called for better and more opportunities for First Nations people to tell their stories, in their own voices, with their own sense of ownership. That doesn’t mean consultancy for a game led by non-First Nations voices. Per Armstrong, it’s about buying into storytelling and culture, investing in people, and the relationality of those people.

Previously, both Armstrong and Collard worked for Awesome Black, a social enterprise designed to elevate the creativity of First Nations talent through a variety of mediums – film, television, radio, video games, and beyond. A recent restructure meant plans for Awesome Black’s debut video game were halted – but in the development process, Armstrong and Collard discovered how powerful First Nations-led teams with agency can be.

Country and people are built to last

As Armstrong explained, it’s the people and their experiences that are most important to the game creation process. While this applies generally, it’s particularly important to telling First Nations stories, given their cultural reverence for people and country, and the knowledge that stories live on long after people fade away. These stories are cultural preservation and transmission.

It’s part of why video games are such an important medium for representation: they provide an opportunity to share personal, relatable stories that can be completely immersive. Representation is affirmative for those who see themselves represented, and educational for those who don’t. We need that level of empathy to drive change, and to create a more cohesive society.

“Immersion evokes empathy,” Armstrong explained.

As Collard added, it’s essential to have authentic, agency-driven First Nations stories told, as these stories are essentially being built from the “ground up.” Swathes of First Nations history have been lost over the last decades, thanks to a variety of abuses and mistreatment on all levels of society. These are stories that must be told, to gain a greater understanding of First Nations people, and to build opportunities for a brighter future.

Read: Tales of the Shire has taught ample lessons in leadership

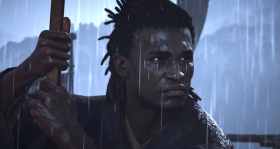

Armstrong called out game studio Guck as being exemplary of a valuable, agency-led approach to game creation and storytelling. This studio is currently developing Blaktasia, a mobile adventure about restoring the bush and saving animals, while facing down a corrupting force known as the Murk.

The game is inspired by Indigenous Australian culture, art, and practices, and has been developed by a pioneering “100% Aboriginal-Led” team. With the support of Screen Australia, Guck has spent the last few years realising its vision for Blaktasia, and working to create a game that represents a milestone achievement for game development, and authentic representation of First Nations culture.

Rather than being sidelined as storytellers or simply consulted for story work, the First Nations folks at Guck are involved with every step of the game development process: creating art, design, gameplay, narrative, and beyond. It allows for more holistic representation, and a shared, family-like approach to creation.

When First Nations folks consult in limited capacity, there is often a lack of nuance in this representation. No amount of careful research and good intentions can allow a non-First Nations creator to fully understand the First Nations experience. And as Armstrong outlines, it’s a shame to see these stories used to drive profits for organisations led by non-First Nations people.

Culture should come before profits

The path to change in this regard is not easy. Video game sales are increasingly driven by discoverability algorithms, and with no real precedent, tags like “First Nations” or “Aboriginal” come up blank. As Armstrong says, publishers looking to elevate these stories will likely blanch at empty tags. It’s a chicken and egg situation. You need the representation to have the representation.

Despite this, there is a real hunger for telling First Nations stories. First Nations folks are excited by the opportunity for representation. Non-First Nations folks are driven by a curiosity, and a want to be more understanding and inclusive. Games like Broken Roads, on which Collard served as a consultant, are exciting prospects for discovery and learning.

Any approach to representation should be careful and grounded in reality, but as Armstrong says, we also need something more tangible: “You have to find a really good partnership with someone who’s looking for a unique story, and a unique opportunity, and willing to lose money on it, because of its cultural value.”

This challenge is compounded by the current state of the games industry, where publishers are being far pickier with their choices. The reality is that games must make money, and as the games industry is subject to severe economic downturn, opportunities for elevation of First Nations-led stories are thinning.

Regardless of these circumstances, these stories are needed. They should be understood not in terms of money, but in their potential impact. First Nations people bring a unique lens to the world. They are incredibly unique storytellers and creators, and their work should be given space to breathe. Even in this, First Nations people should not be relegated to cultural consultants, or have their stories sold to those who’ll always make more money. They should have the opportunity to share their stories with agency, and with ownership.

“We’re doing something more than just creating a game,” Collard said. “We’re creating a community. We’re making a strong message. We want something to last.”