People always ask what I’m playing, as if this is easy to answer. It’s really not, given the uncategorisable and genre-blending experiences everyone is making at the moment. Recently, I surprised myself by succinctly answering, ‘Right now, I’m obsessed with city builders set on large creatures.’ The person who asked was like, ‘what,’ so I oriented my laptop to reveal Meeps, fussily at work, on the back of a spacefaring turtle in World Turtles. ‘That’s a weird game.’ I’ve also been playing The Wandering Village, set on a loveable, six-legged, grassy maybe-stegosaurus, and Before We Leave, which actually plays out on tiny planets, but whose sequel will be atop an interstellar whale.

I’d never previously thought of ‘city builders set on large creatures’ as needing to be discreetly classified. Now, I’m so in love with this (very specific) genre that it’s not even funny. I’m captivated by the multiple perspectives, integrated layers of gameplay, recontextualisation that is driven by creature autonomy, and occasional narrative twists. Not to mention feeding my home with a catapult.

A Butterfly Effect

Games layer interdependent contexts and gameplay. World Turtles, The Wandering Village and Before We Leave, are certainly not the first to do so. SimAnt (1991) comprised underground colonies, where you’d build and manage larvae/food, surface levels, where you could take down a spider, and a garden/kitchen overworld, where the eventual aim was to strategically drive Man out of his house. Concurrent engagement with each layer contributed to an overall outcome.

In SimAnt, there was also a dog. You couldn’t play on the dog, but what if you could? SimFlea, perhaps, or Planet Flea Circus. You’d build infrastructure, micromanage supply chains, explore and expand. The dog might scratch (if you’re being itchy), or chase a cat (if they were badly trained), and you’d have to deal with the ensuing destruction.

So, in addition to contextual layering, the first things that distinguish ‘city builders set on large creatures’, are that your home base is always in motion and that it makes, at least some of, its own decisions. So it’s less like colonising a stationary patch of dirt, more like colonising the dog.

In this way, I began World Turtles at the mercy of my turtle’s path through celestial debris, surviving and exploiting it, before understanding that the goal of the early access experience is to construct a catapult, ball some grass and fling it enticingly towards beneficial pockets of space (with varying humidity, temperature and flux), or away from harm. After spending a good few hours myopically constructing the supportive infrastructure required, greater control over the turtle’s movements felt like an immensely satisfying reward.

A Guiding Light

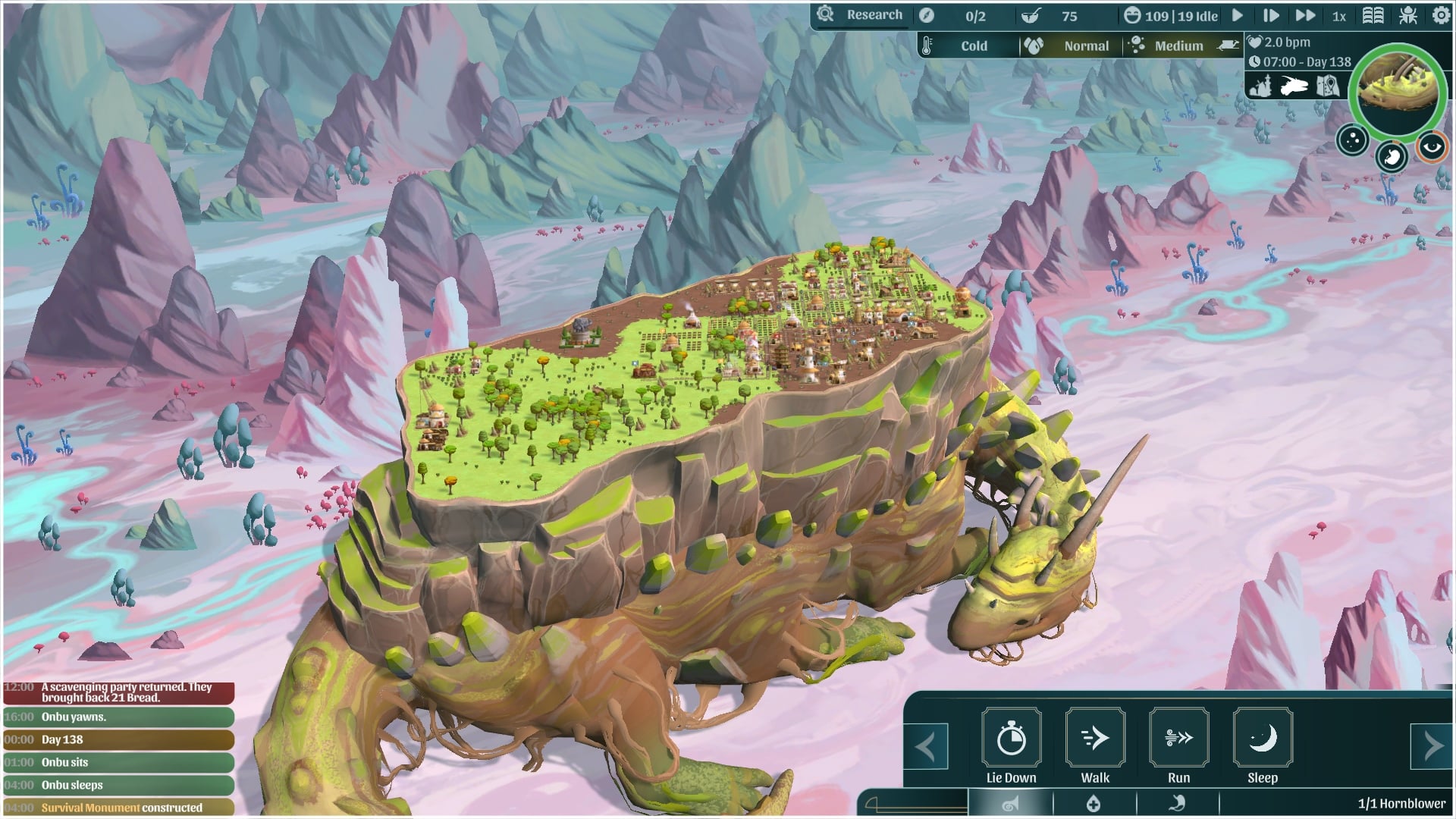

Similarly, in The Wandering Village, you can fire mushrooms into your large creature’s mouth, to build trust, or because you want it to be full when it’s approaching constipation-causing, map-based food. Caring for the stegosaurus-like creature, named Onbu, might involve sending doctors to its body in a hot air balloon, and not recklessly harvesting its spines (for building materials), its blood (for food), or its bile (for incinerating poison infested plants).

A trusting Onbu will accept more of your commands, delivered via a curly, musical horn. As well as directing it to avoid hazards, like waiting out a storm, the game’s primary dilemma is whether your city is presently fortified more effectively against poison or famine, informing which kind of biome it’s safer to wander into next. If Onbu rebels, be prepared for life to get difficult.

Unlike World Turtles, in which accessing the bigger picture takes time, the layers of The Wandering Village are all immediately relevant, even down to planning early wood scavenging missions near the (overworld) fields where Onbu is likely to choose to nap. It occurs to me that there might be a dark playstyle, in which you enslave Onbu. I’m not sure if this is planned for a final release but given the environmental threats to the city and Onbu are so inextricably linked, and only differentiated by scale, developing a positive relationship seems vital.

The Wandering Village gets progressively more challenging, requiring an increasingly resilient city, and is roguelike in structure, but it is possible to reach an optimistic ‘ending’, rather than playing until the village, or Onbu, is dead. And so, hopefulness also seems integral to this ‘city builders set on large creatures’ experience. If you’re asking a creature to trust you, you have to then take responsibility for protecting it.

A Blind Eye

Mechanically, layered contexts have to allow the player to ‘set and forget’. This is most obviously seen in Before We Leave which (gradually) becomes a truly massive experience. Initial stages are concerned with minutiae; conscientiously reserving hexes for roads, in a way that reminds me of Dorfromantik, or its fellow Kiwi game Mini Motorways, then meticulously making sure that harvesting and manufacturing will run independently, for as long as possible.

Before We Leave opens with Peeps emerging from an underground shelter. I imagined their ancestors seeking respite from pollution, which is the game’s initial gameplay antagonist, but the story becomes progressively more profound. The first twist occurs when you leave your island, and discover additional research types and resources. The next, when you leave the planet. Soon, you’ll be trading between planets, each with several islands and, without spoilers, coming to understand why the game’s sequel, Beyond These Stars, will be set on ‘Kewa’, the Māori name for the Southern Right Whale.

Although you have crafted cities so carefully, tile by tile, you may stop noticing them entirely. Consider Spore, in which you were a cell, creature, tribe, global civilisation and space empire. There were small, enduring consequences, based on collecting DNA or choosing socialisation over hunting, but each life stage was essentially separate. In Before We Leave, every piece of your cities remains active and important, even as your engagement becomes godlike.

A Finer Point

The poignancy of ‘city-builders set on large creatures’ relies both on grandness and detail. If your adorable Onbu died, that would be sad. The fact that this would also condemn any number of tiny people, shrouded against the elements in blue robes, and red veils, tying balloons to trees that need harvesting, bent double to weed a herb garden, enriches this sadness in ways that are aesthetic, specific and personal.

Presently, it’s unclear what wider, celestial horrors might await Meeps in World Turtles, but the fact that they eat pineapples, onions, cabbages, grapes, aubergines, capsicums, corn, strawberries, and so on, rather than ‘food’ makes their existence infinitely more precious. They have babies, so the survival of youngsters is also at stake. The capacity to tell a vivid, emergent story in my head about this is enough to provoke RimWorld-level fear.

Small moments of explicit story in The Wandering Village and Before We Leave add significantly to the experience. Sam Barham, Creative Director on Beyond These Stars, says the sequel will, ‘go into backstory in more depth, exploring the space whales’ history, as well as the Peeps’ reason for jumping onto Kewa’s back and journeying into the unknown.’ I am excited to learn more.

Hope Springs Eternal

Let’s acknowledge the traditional beliefs that connect humanity to Earth and creatures, especially the range of creation stories that place us on the back of a turtle; the Hindu Akūpāra, Chinese Ao and Lenape turtle, which grew to accommodate life. Would our species be quicker to solve environmental crises if we believed (more widely) that we were orbiting the sun on a living creature, who was harmed by our behaviour? A better appreciation for the interconnectedness of life and the complexity of Earth’s systems would surely help.

Despite the pollution, poison, harsh weather and general chaos, for me these games inspire hope for the future. They’re a reminder that, no matter how carefully organised we may believe our lives to be, there is always a bigger picture. And, in turbulent times, it’s easier to rebuild if you can coax your world to lay down for a nap, rather than if it is marauding towards disaster. These multi-layered experiences highlight the value of planning, oversight and cooperation, very neatly.

Perhaps ‘city builders set on large creatures’ are mostly just survival, or tower defence games, at heart. I’m actually glad that the perennial question, ‘what games do you play,’ isn’t easier to answer. It means that designers are exploring context creatively, like these important metaphors for sustainability that are also fun to play, at face value.

Next time I’m asked, I hope to be trying to explain another unique, unexpected, mash-up of experiences that inspires as much thought as building a city on a map that can move and think for itself.

Essential Casino & Betting Guides

Looking for the best casinos or betting sites? Below you’ll find our recommended guides that players love right now.