Darth Vader levels the sights of his pistol at Superman, zeroing in on the Pac-Man backpack he has ‘waka-waka-ing’ away on his back, as Indiana Jones sits in the background playing Galaxian with Lebron James. Elsewhere, Lebron teams up with Shaggy from Scooby-Doo! to beat the life out of Gandalf and Bugs Bunny. Crazy as it sounds, these are all very real things to find in your typical video game session today.

There’s something about seeing characters from different artists, authors and creative minds the world over – if not just the literal appearance of a famous person – take to the same proverbial field, most often to positively clobber one another. It’s utterly absurd, and I love it.

If somehow, you could travel back in time to 1999 to show people picking up Super Smash Bros. for the first time just what games would be like in twenty years, they’d probably look at you like you were a Looney Tune yourself, before asking you who LeBron James was.

Looking at

Since then, crossover fighting games continue to thrill the synergistic sensibilities of enthusiasts – the number of new releases, and the rosters within them, seemingly multiplying each year. From the indie scene to triple-A, guest characters to franchises built on crossovers, this is your guide to how collaborative IPs changed fighting games.

- Everybody’s Here: A Multiverse’s Worth of Crossovers

- Small Dev Teams, Big Rosters

- The Perfect Battleground

- One Character Gimmicks – Representing Personas

- Modern Fighters and Misfires

- Round Two: A Crossover Renaissance?

Everybody’s Here: A Multiverse’s Worth of Crossovers

The fighting game scene seemed to be the furthest along on the matter of crossovers until recently. After all, fighting games have been the perfect meeting place for characters of different backgrounds and origins to duke it out – putting what they represent on the line both in-game and out, and turning the age-old playground arguments of whether your favourite could beat my favourite, into reality.

It’s no wonder that, with pop culture being the birthplace of excess, these ideas found their way into the industry, which is exactly what happened in 1996 – with the release of X-Men vs. Street Fighter. As one of the earliest examples of a mainstream crossover fighting game, X-Men vs. Street Fighter predates Smash Bros. by three years, marking the first cross-company fighting game crossover and kicking off the Marvel vs. Capcom franchise.

In regard to ‘in-house’ crossovers, the folks over at SNK had already been combining their own characters in The King of Fighters two years prior to that. At the turn of the millennium, SNK would eventually form one-half of 2000’s SNK vs. Capcom – featuring an early system that allowed players to use the mechanics of either of the companies’ games beyond just their characters.

Though the series may have faded from the limelight, this founding father of crossover games may soon see a reignition. Should the titles’ hiatus persist for another twenty years, many others have already entered the proverbial ring that SNK vs. Capcom established.

Small Dev Teams, Big Rosters

With today’s accessibility of game development, even indie studios are dipping their toes into the water – 2018’s Indie Pogo and the upcoming Fraymakers saw the likes of Shovel Knight, Octodad and Diogenes – the hammer-wielding shirtless guy in a cauldron from Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy – grace their rosters. Fraymaker’s developer, McLeodGaming, is known for their game Super Smash Flash 2: a fan addition to the franchise. Super Smash Flash 2 ran on the now discontinued Flash Player, featuring fully functional online multiplayer and the addition of characters such as Naruto.

The demand for crossovers has always been evident in the fan-made games community too – ROMhacks, mods and original projects all express the unified desire of fans to see their favourite characters represented in video games of all kinds.

While indie and fan games might never have quite the same polish as the fighters from big studios, this gap is steadily decreasing as the capabilities of mods and development engines progress. Additionally, and maybe most importantly, without the corporate sanctions of official games, fan titles are opened to the wild west of everything that dares exist, so long as they can avoid the notoriously litigious eyes of companies such as Sony or Disney.

Read: Elden Ring players mod Darth Vader into the game

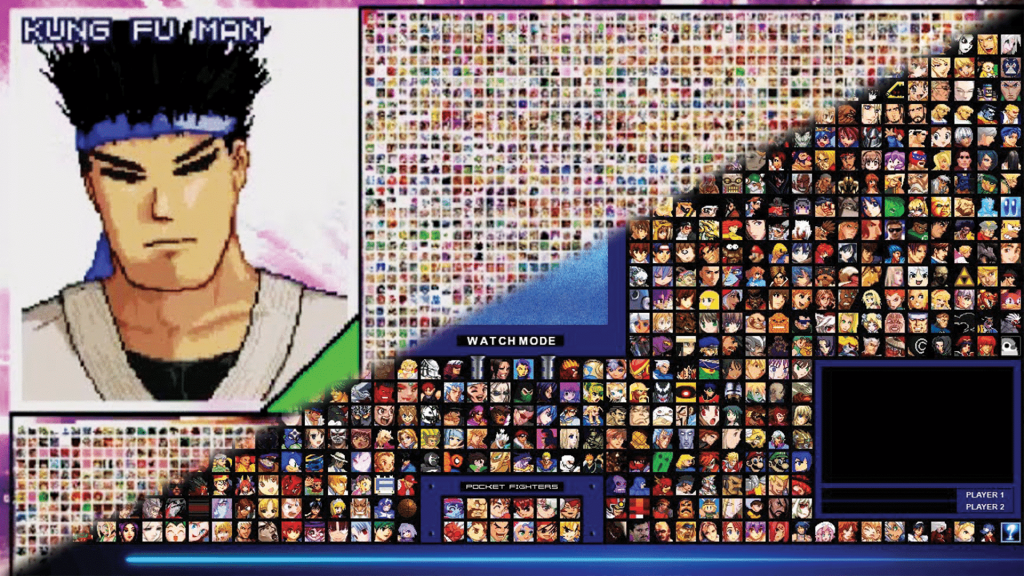

Perhaps one of the concept’s wildest realisations is MUGEN, a fighting game engine released in 2000. Or, more specifically, Everything vs Everything (or EvE for short), a character selection mod for MUGEN. MUGEN allows players to create, import and export any manner of fighters that their heart so desires. EvE is one such character select screen mod – initial versions accommodating approximately 750 characters, while later, diehard screen packs make space for upwards of 4000 characters.

At this point I’m convinced every character portrait is three, maybe four pixels max.

A range of player characters of such an immense scale could be enough to get people talking, or rather, playing in and of itself. Even though game balance may not be at the forefront of design philosophies of overblown rosters, they lend a longevity lasting hundreds of hours before the novelty of every fighter is exhausted – and even then, many more hours spent simply witnessing the interactions between different matchups.

With the agency of fan creators, MUGEN characters from gaming mythos in the likes of Pokemon’s MissingNo. spawn their own character archetypes, ‘cheap characters’ and ‘cheapies’ – spanning power levels from gratuitously broken to breaking and rewriting the game’s engine to their whims, and lending the signature indie meta-game vibe.

No matter how overpowered though, with a sufficiently large fighter cast, game balance might look like simply arranging characters from a list numbering thousands into roughly equal ‘tiers’, as is already common in conventional fighting games. The overwhelming nightmare of working to ensure characters are all roughly on the same playing field is replaced by the community solution, and simply becomes a matter of pitting one character against a relative equal.

Such is the exact premise of SaltyBet – an online streaming service where users wager virtual points on computer-controlled MUGEN fights. The stream runs nonstop, featuring tournaments between characters of algorithmically assigned ‘tiers’, and player-curated ‘exhibition matches.’ Like any real fighting game or sport, SaltyBet has its fair share of nail-biting bouts down to the line, and underdog upsets – except the only personalities behind every victory and defeat, are the fighters themselves.

SaltyBet goes to show that audiences don’t need to play a crossover fighting game themselves, or even see real people play characters to warrant a crossover combat spectacle of its own.

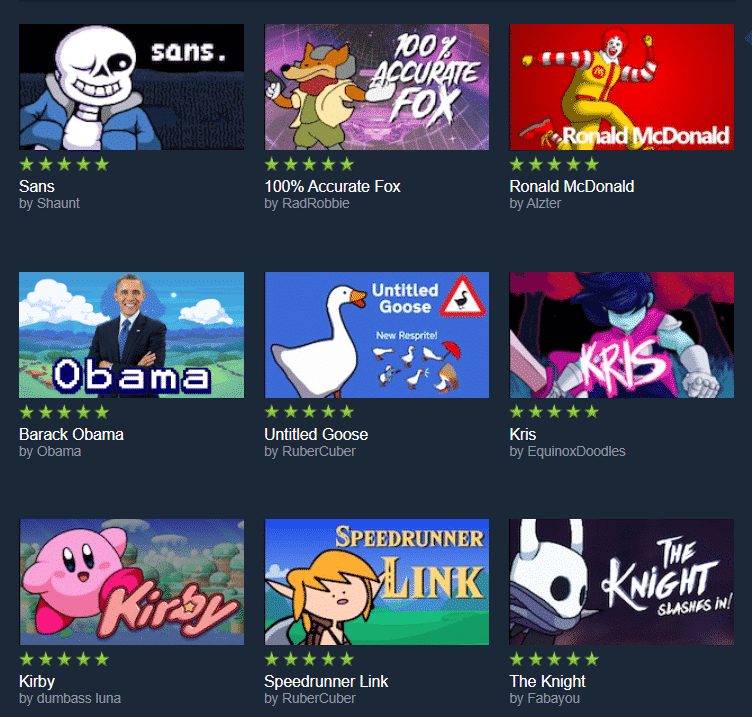

Indie games and player-developed ‘workshop’ content are in themselves, a crossover – indie platform fighter Rivals of Aether released to Steam in 2017, and opened its gates to the Steam community workshop in a highly anticipated update, four years later. By then the game already debuted its two guest characters: Ori and Sein from Ori and The Blind Forest, and Shovel Knight from the game of the same name. With its Steam Workshop update, Rivals of Aether effectively added, to date, almost three thousand characters with the update and all their collective meme value with them.

Thanks, Obama

The Perfect Battleground

Just what is it about fighting games of all genres that seem to seamlessly bring all sorts of characters into their fold?

While I could carry on name-dropping the outlandish characters that have found their way into fighting games, there’s a point to be made in how fighting games adapt characters from different cultures, worlds or even universes – no matter how simple their gameplay and/or control schemes may be.

Fighting games often mark a faithful recreation of their source material, in player character form. When it comes to combining personality and gameplay, fighting games are no stranger – doing so regardless of whether or not the characters in question come from another property. Add in the genre’s penchant for weird and wacky characters, and more often than not, any collaborative character that finds their way into a fighting game’s roster fits right in with the rest of the cast.

Take for example Freddy Krueger – the iconic undead killer from the 1984 horror film Nightmare on Elm Street. When he’s not murdering teams of teens on caffeine, in their dreams while they scream using his trademark weapon – a leather glove with five knives taped to his fingertips – he’s flaunting his fashion sensibilities in a fedora and what can only be described as a dollar-store Christmas sweater. What a look. I don’t think anyone would contest the fact that Krueger is a veritable freak, any day of the week.

Raise a finger for every horror franchise guest star in Mortal Kombat, Freddie

But in the world of Mortal Kombat – home to Kombatants like mainstay Scorpion, the skeletal fire-breathing ninja, and newcomer D’Vorah, who is really just some bugs in an assemblage that resemble the human form, no one would bat an eye at nightmare stalker Freddy. Krueger’s gruesome style is also right at home amongst the game franchise responsible for the moral panics over video games in the 90s, and the resulting creation of the ESRB rating system.

One Character Gimmicks – Representing Personas

There’s also something to be said about how fighting games are often so willing to embrace the chaos of outlandish gameplay systems.

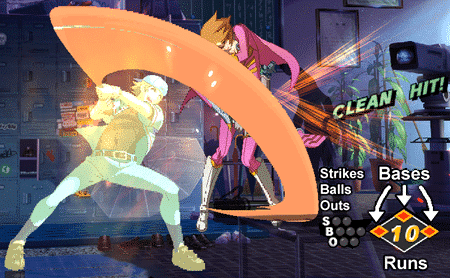

To illustrate the point, let’s talk baseball – specifically, the baseball that exists as a unique set of mechanics nested within a fighting game. Bear with me while I explain the intricacies of the character Junpei in Persona 4 Arena Ultimax.

Junpei’s fighting style relies on a kind of baseball minigame within regular matches. The overall goal is to reward the Junpei player with a power-up for satisfying the various conditions of a baseball-themed system. It even shares all the terminology.

Bases, balls and runs are acquired from a variety of in-battle actions, including reflecting projectiles and landing blows with the baseball bat, or striking the opponent with ‘Clean Hits’ or ‘Home Run’ attacks.

Like actual baseball, 4 balls earn you a base, and filling the bases scores you a run. While you can’t lose your runs, missing a bat attack earns you strikes, and getting hit strikes you out instantly. Accumulate three strikes and you’ll get an out, three outs and you’ll lose any bases you currently have filled.

If you can avoid that and reach ten runs, you gain the Victory Cry mode, which grants a wide variety of power-ups – multiplied for every ten runs thereafter. Victory Cry also enables you to land a ‘Clean Hits’ – striking the opponent at just the right angle, rewarding the player with more runs, the potential for brand new combos, and a satisfying ‘ping’ sound every time you land one.

Again, this isn’t a deep and complex system for a baseball fighting game like Lethal League, but a mechanic made for just a single character in Persona 4 Arena Ultimax – a character and mechanic that hasn’t appeared in any other game since.

So why go put so much effort into a one-off character, never intended to return? From a developer’s point of view, surely one character gimmicks are a gross over-investment of time and resources?

There are two possible answers to this – the first and most optimistic being simply that such details are simply a labour of love above and beyond the required. Looking a little closer, if studios of varying sizes have been able to persist with this practice then it’s likely that the passion and love expressed in these games drive small communities of die-hard fans of a character, if not the entire game community thereof, to become invested in these larger-than-life personalities – enough to have a significant impact on the success of a game.

Examples like this showcase the fighting game scene’s dedication to individual characters – taking their place beside traditions of making rumours, mistranslations and inside jokes into fully fleshed-out characters.

If you want to see personality and style make its way into gameplay, you needn’t look further than unique character mechanics or ‘gimmicks’ such as these. One-character gimmicks are a game’s way of breaking rules, transforming existing ones, or transcending the game entirely, all for the purpose of making a character really hit home (no pun intended).

As a personal fan of gimmick characters, to me they represent the heart of the fighting game community that leads to moments like the ‘Cell Yell’ at this year’s Evolution Championship Series (EVO), that highlight a collective love for a character – projected onto the community mythologies of the competitive stage.

We’re seeing newer games integrate unique one-off mechanics more and more. If individual characters already have their own styles of play, there’s no reason for newcomers to do the same.

Street Fighter’s Akuma and The King of Fighters’ Geese appear as guests in Tekken 7, bringing with them the unique mechanics from their own games: EX moves and MAX mode respectively. The transposition of their styles and systems, in tandem with their distinctive control schemes, creates an entirely new experience that is in my opinion as exciting, if not more, than either of their native franchise titles at the time.

Putting in the work to translate character controls bridges game access barriers – allowing players to focus their attention and skills on what’s new, different and unique to the crossover game – rather than having to worry about learning their favourite characters again and having their existing habits and experience work against them in a new environment.

Porting characters with their respective mechanics and controls reintroduces guests in ways that feel familiar – muscle memory and the somatic elements of games work for developers here, cementing the feel of a character in the minds of players.

Of course, it’s not all about the feel – adapting the aesthetic of characters has changed alongside the development of games overall – earlier crossover fighters would feature hand-pixelled or, at the very least, ports of existing sprites into a different engine, bringing the flair of an IP’s personality with the spin of the world they were being brought into.

The move to dynamic rendering engines takes the process to new levels, where effects such as cel-shading or photorealistic lighting techniques can be more readily applied in unison to characters and environments than ever before.

While characters from similarly styled works, such as anime-inspired styles, lead to strong and cohesive crossover results, a vastly different aesthetic also presents the opportunity to feature a character in a brand new light – whether that be more gritty and grounded, stylised and cartoonish, or from 2D to 3D and vice versa. Case in point, Battletoads‘ Rash in Killer Instinct, and Tekken’s already very anime Lars moving to Naruto Shippuden: Ultimate Ninja Storm 2.

The former’s appearance even harkens back to one of the earliest crossover fighting games: Battletoads & Double Dragon: The Ultimate Team, a 1993 combination of the Technōs Japan and Rare properties.

The design space of a crossover allows creators of both the origin and destination work to create something entirely new, like fangames, to operate without the restraint required of a more serious handling of an IP. There’s a certain excitement in the reimagining of characters – seeing someone in a place we’d never thought they’d be, like a man on the moon, or Waluigi in Smash.

Modern Fighters and Misfires

With this ease of access, coupled with the increasing willingness of companies to get creative with their IPs, we’re starting to see collaborative IPs less as bonus appeal and more as the core premise of an entire game genre.

Super Smash Bros. Ultimate and the wildly successful release of MultiVersus, sees crossover fighting games inherit the spirit of wild encounters and strong character identities today – showing that they can still dominate the market, in both free-to-play, cross-platform, and console-specific, triple-A price tag titles.

These games can be understood as having ‘looser’ overall combat systems – facilitating the basics of what a fighter can and can’t do, while everything else that follows is the byproduct of character design and intended playstyle.

Ultimately, the rules of the game have evolved – becoming a conduit for characters, presenting a space where their personality can be realised. While the idea might sound like a capitalist’s recipe for corporate shill wrapped in a video game, the effect is quite the opposite.

Read: MultiVersus races past 20 million players in its first month of release

Because of their appeal that turns niche into widespread, it’s hard to find examples of crossover fighting games that fall particularly flat – say what you want about individual titles, but fighting game crossovers often originating from established or trusted developers means that they’re usually well-developed experiences.

Over twenty-odd years of titles though, there’s bound to be at least one swing and a miss – foremost in my mind is 2020’s Bounty Battle, another title that features a collation of indie game characters. What little gameplay you’ll find online looks robotic, clunky, and, perhaps worst of all, commits the collab cardinal sin of featuring very little of the personality behind its rich cast of characters. While I haven’t played Bounty Battle personally, from the game’s poor overall reception, I’ll say with some confidence that these factors did the experience no favours.

Also outstanding in fighting game collaborations, Puyo Puyo Tetris. It’s a crossover between adorable Japanese tile-matching game Puyo Puyo and, of course, the classic tetromino-stacking game Tetris. Rather archaically dubbed a fighting game by the wider community – despite its unconventional appearance, the head-to-head action strategy game has even taken side-event spots at the annual fighting game tournament, EVO, over the years.

The game’s various game modes are all apt analogies for the design philosophies of crossover fighting game mechanics. Among these are Versus Mode, Swap Mode and Fusion Mode.

Versus Mode simply places players side by side with the gamemode of their choice. If both choose the same game, then Puyo Puyo Tetris is essentially that game. If one of each is chosen, then the game simply translates the performance of one game to the other in the number of grey penalty pieces dropped on the opponents screen. By its nature, Versus mode only requires players to engage with the game systems of the collaborative properties that they so desire.

Swap Mode instead makes players engage with both systems equally – swapping between game modes every 25 seconds. The extra complexity of this change arises when players must not only manage the game they are currently playing, but the position and plans for the other game mode in conjunction with it.

Finally, is Fusion Mode, a direct combination of the two games where both puyos (the game’s blobs) and tetrominoes occupy the same space under their own rules, with the exception that the tetrominoes can smash through the puyos (it really is a fighting game). In Fusion Mode, players engage with a combination of both games’ mechanics simultaneously.

While Puyo Puyo Tetris might not be a groundbreaking synthesis of the two games, it is an elegant mediator that mashes them up with simple, but varied bridging mechanics. The sequel, released in 2021, Puyo Puyo Tetris 2, leans even more into its fighting game label – adding ‘Skill Battle Mode’, which features

Round Two: A Crossover Renaissance?

The future of crossover fighting games looks as bright as ever, though it might be taking a very different form from what we’re used to. So what’s next?

Like our aforementioned killer Freddy Krueger – who made his way into the real world, once again, with the Kylie Jenner x Nightmare on Elm Street makeup set, crossovers are finding new ways to stay on-brand while getting progressively off-brand in ludicrous ways.

Unless you’ve been out of the loop for the last twenty years, I’m sure you’re aware by now that crossovers have been far from confined to the fighting game genre. Video game collaborations are making their way everywhere – not only taking in characters from mainstream media, but breaching the boundaries of games. Every new transmedia release seems to one-up the last one and each blurs the lines between film, games, and reality.

Stay tuned for our next instalment in this feature, where we’ll be looking at why mainstream media’s big players are shaking hands with video game developers, how collaborations have become the driving force of one of the most popular games today, as well as times where, in the case of game collaborations, more wasn’t always better.