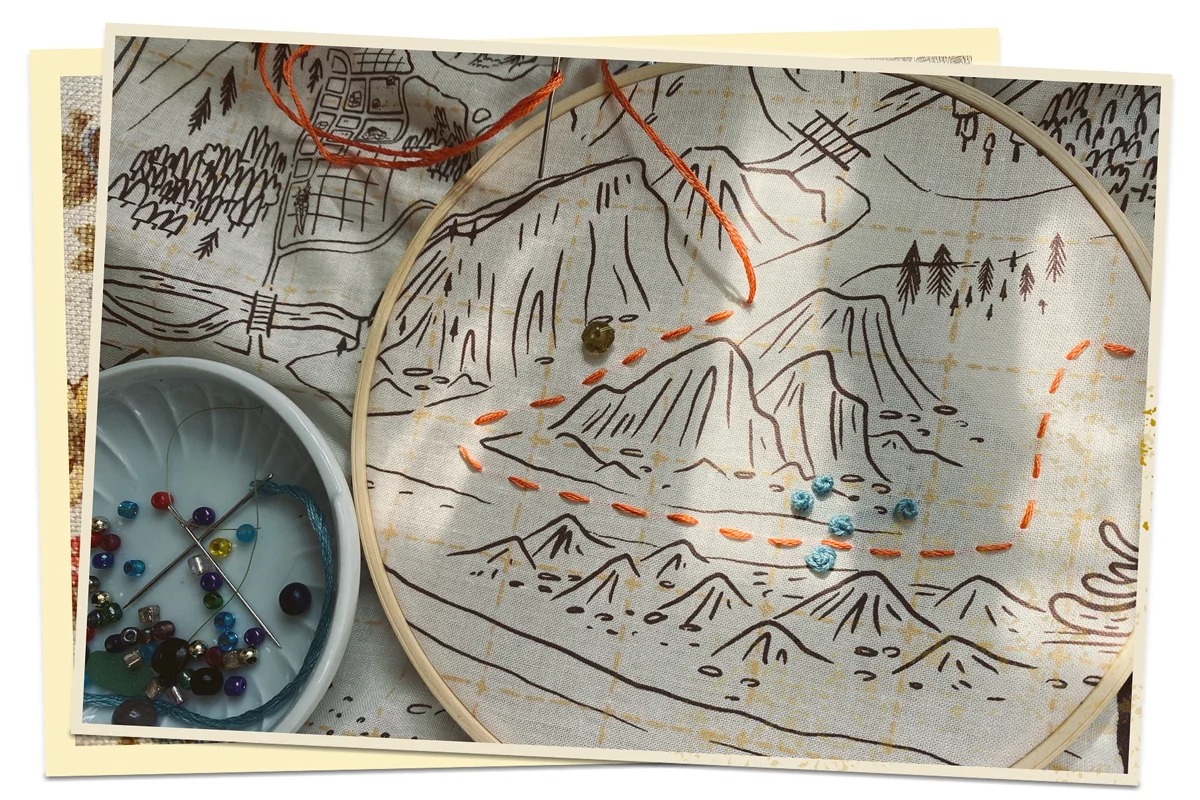

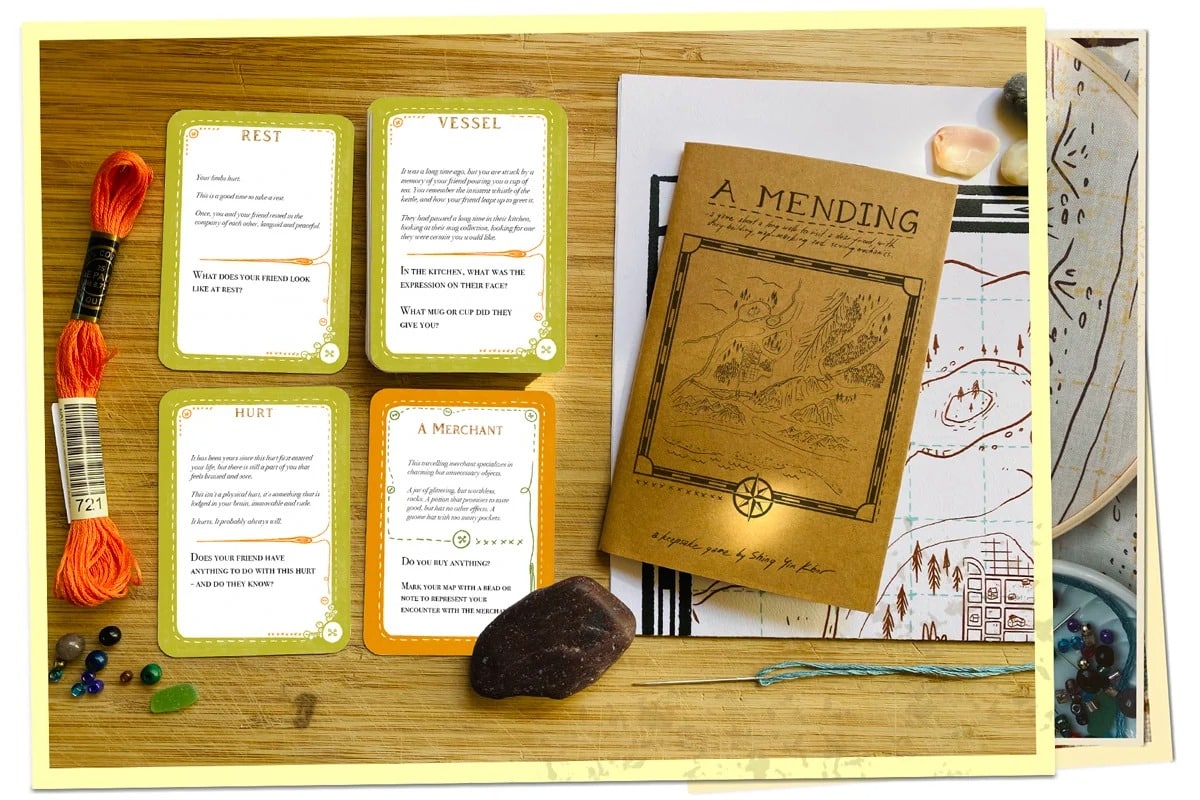

A Mending, by artist Shing Yin Khor, is a game that blends story building and handicrafts. Players travel to visit a friend they have long been parted from, marking their journey by sewing and embroidering across a real-life fabric map.

A generous deck of prompt cards guides players through their trip, from meeting eccentric merchants and bards, to composing memories about their distant friend, and reflecting on the nature of various emotions connected to the friendship.

The rules are flexible, and are there to guide and inspire, rather than restrict. Players can skip cards at any time and are not bound to complete the journey itself. The creator even suggests cutting up the map when deciding to stop, and then mending it, if choosing to resume later.

Though the game can be completed in a few hours, I crafted my journey over several weeks, embracing the intimate connection I’d forged with my characters by keeping a slow pace.

At one point, I found myself tearing up when I decided to part ways with a dog that had accompanied most of my journey. (I left it with a family before climbing a perilous mountain – I’m not a monster!) To represent the dog, I’d been embroidering a second path alongside my own, and ceasing that path was unexpectedly devastating.

A Mending leaves players with a meaningful keepsake to remember their journey. The crafting process also offers a unique contribution to how games engage with collaborative storytelling traditions.

Games, handicrafts and storytelling traditions

Textile crafts traditionally sit in the realm of women’s creativity and labour. It’s not often that we find ourselves connecting sewing to games, where the latter is typically tied to the digital, or to hypermasculine themes.

Yet handicrafts have their own neat history in gaming (and I’m not just talking about Yoshi’s Woolly World). Mattel’s Barbie Fashion Designer flew off the shelves in 1996, and has been credited with spearheading the development of ultra-gendered ‘pink games’ studios shortly after. Players design clothes for Barbie on their computers, then print them out on printer-friendly fabric for their dolls.

Read: What happened to ‘Girl Gamer’? Searching for Nintendo’s forgotten pre-teen girl magazine

In 2000 and 2001,

More recently, in 2016, an initiative led by Sarah Hendricks, Bri Williams, Josh McCow and Anne Sullivan created an open-sourced game called Loominary – where a physical loom can be used to play a set of Twine games. Different coloured yarn represents different choices, and so the player is again left with a keepsake – their own unique scarf.

The aim of the Loominary project is to bring digital storytelling to crafting communities, which are predominately women. Their artist statement reminds us that these communities ‘have created story artefacts for many years, but these stories have not been engaged computationally’ – likely referring to the presumed mismatch of digital storytelling with textile crafts.

Women have told stories through tapestries and shared tales in sewing circles long before the digital.

Folklorist Maria Tatar points to mythical figures like Philomela and Arachne, whose handicrafts gave voice to injustice. Arachne was turned into a spider for weaving a tapestry that was critical of the ancient Greek Gods. Tatar even links Charlotte from Charlotte’s Web to Arachne, who ‘revitalises language’ by spinning words into her web.

While playing A Mending, there was a quote from Tatar’s most recent book that resonated so poignantly with me:

‘How strange and yet also how logical it is that so many of our metaphors for storytelling are drawn from the discursive field of textile production. We weave plots, spin stories, fabricate tales, or tell yarns – a reminder of how the work of our hands produced social spaces that promoted the exchange of stories.’ (The Heroine with 1,001 Faces, p. 64).

These modern keepsakes – whether it be an embroidered map from A Mending, a scarf from Loominary, or even an over-the-top wedding dress printed from Barbie Fashion Designer – they reflect a story and an experience and, even in solo play, they are rooted in collaboration.

Crafting stories together through journaling

A Mending suggests players optionally record their responses to the prompt cards in a journal, to act as a companion to their map, situating the game amongst the growing solo journaling genre of tabletop games. Solo journaling games can be played independently, and are usually driven by storytelling prompts and sometimes dice or other objects.

Two that I’ve recently been enjoying are:

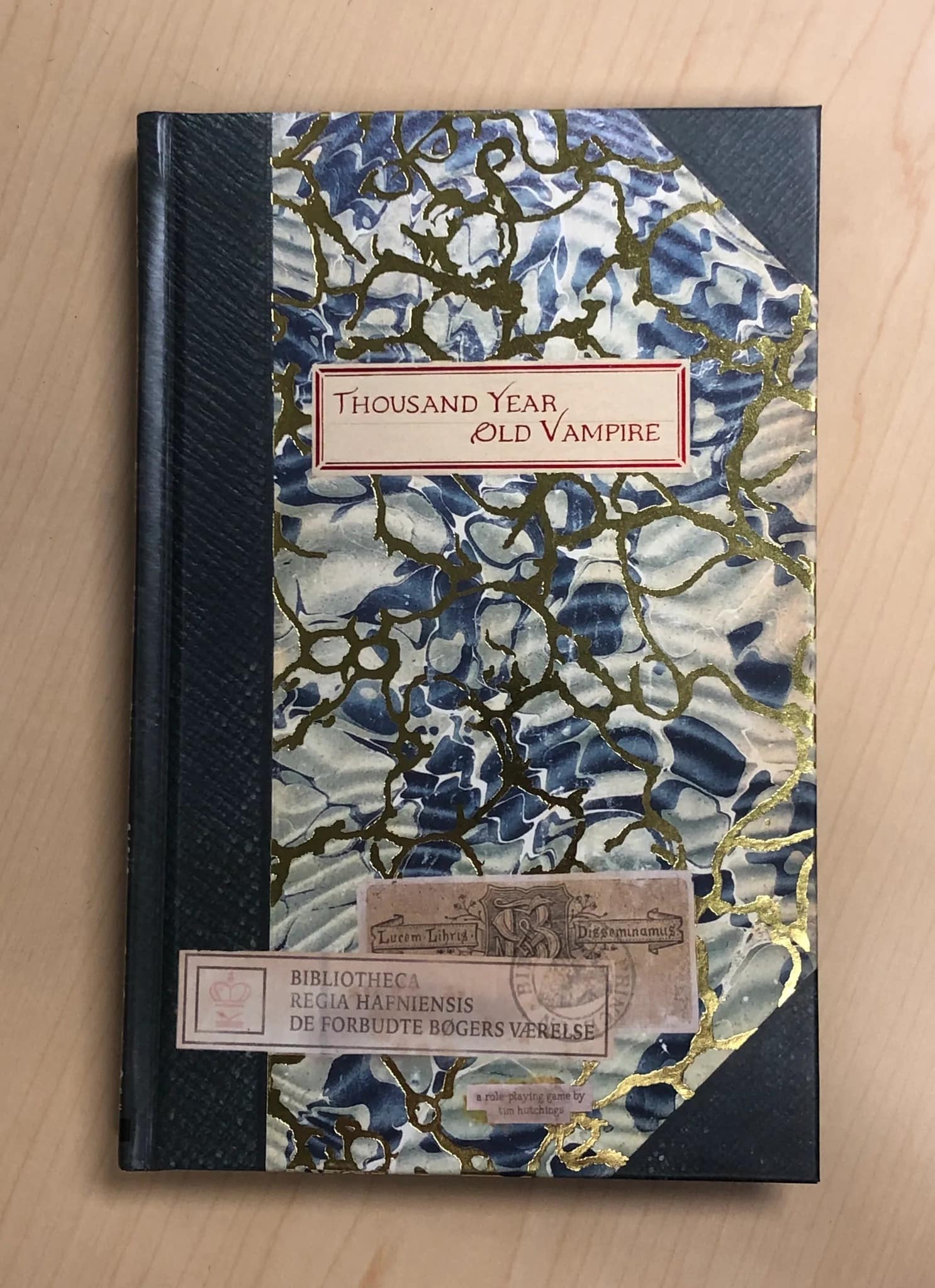

Thousand Year Old Vampire by Tim Hutchings, an introspective roleplaying game about a vampire’s long existence and fading memory. While a PDF is available, the physical copy (pictured) is a stunningly beautiful hard-back book.

Artefact by Jack Harrison, which follows the perspective of a magical item as it’s passed along various hands over long eons of time while lost, forgotten or abandoned in-between keepers. (Artefact also works well as a companion to roleplaying games like Dungeons and Dragons if players want to craft deep histories for special items or weapons).

The journaling process in games like these are charged with a cooperative spirit between the creator and the player.

Traditionally, storytelling was also a collaborative process. Before their famous literary print editions, folklore and fairy tales were shared orally. They changed with each retelling, embracing listener participation and improvisation.

Games frequently place narrative choices in the player’s hands – though it seems that solo journaling and crafting games are taking the next steps in recapturing early storytelling traditions. In A Mending, we see player and maker stitching the story together.

As A Mending’s creator Shing Yin Khor writes in their introduction to the game: ‘Thank you for choosing to make something with me.’