There is a unique charm to playing the original Dead Space (2008) on its original hardware. Upon crashing into the planet cracker USG Ishimura, and being forced to roam its faceless hallways with a desire for dismemberment, I’m struck by Dead Space‘s sluggishness – the way the player-character, space engineer Isaac Clarke, feels heavy, and moves almost as if over-encumbered, like the dense celestial pressure was buckling his knees.

The sense of volatility in unravelling the horrors of the Ishimura is amplified by my decade-old console’s fan ramping up to the next speed, fighting its own impending doom, trying to keep the things on-screen running smoothly (as smooth as sub-30fps can possibly be).

‘The scariest thing about this game is the frame rate,’ I texted a friend, only half kidding.

Remakes

In 2023, video game remakes are in vogue. Capcom proved one model extremely successful in their impressively modernised remake of Resident Evil 2 in 2019, which has become both a catalyst and reference point for the horror remakes that follow it. The developers of the upcoming Silent Hill 2 remake have gestured to RE2 as a source of inspiration, for example. It began a new wave of (and appetite for) remakes, of games that reconstruct – or work in dialogue with – their original versions, in a different manner to the usual slate of high-definition ‘remasters’.

These updated remakes take the core ideas of an original game, and fix them squarely within the contemporary Triple-A tradition. Idiosyncrasies woven into the original version – often seen in today’s light as hindrances or visible signs of age, desperately in need of remedy – are sculpted (or, perhaps, carved away) in the shape of a pristine third-person action game, a genre much more palatable to a contemporary general audience.

Did Capcom kick off a ‘golden age’ of video game remakes? In April 2020, they followed up with their Resident Evil 3 remake, which continued this specific remake tradition (albeit to a far more muted reception). A week later, Square Enix released Final Fantasy VII Remake, their self-conscious, full-scale redux of the original Final Fantasy VII, which actively engages with the concept of what a video game remake even is (something that Kirk Hamilton has facetiously classified as a ‘Super Turbo Remake Plus’.)

These releases created an interesting template for remakes to follow.

Demon’s Souls (2020) was a ‘cleaned up’ version of the original, replacing it with a new visual style; and more recently, Metroid Prime Remastered took a similar approach.

Nü Dead Space

In January, the Dead Space remake, developed by Motive and published by EA, was released to much the same response as RE2 remake back in January 2019 – that is to say, something close to ‘universal acclaim,’ in the parlance of Metacritic.

Inevitably, and perhaps by design, the Dead Space remake has drawn comparisons to the RE2 remake. Its updates to its original version, however, are far less radical, a sign of both the original’s relative youthfulness in comparison to the original RE2 – it’s a remake of a PlayStation 3 game rather than a PlayStation 1 game – and the raw strength of its foundation, the 15-year-old hard work of the original Visceral Games team.

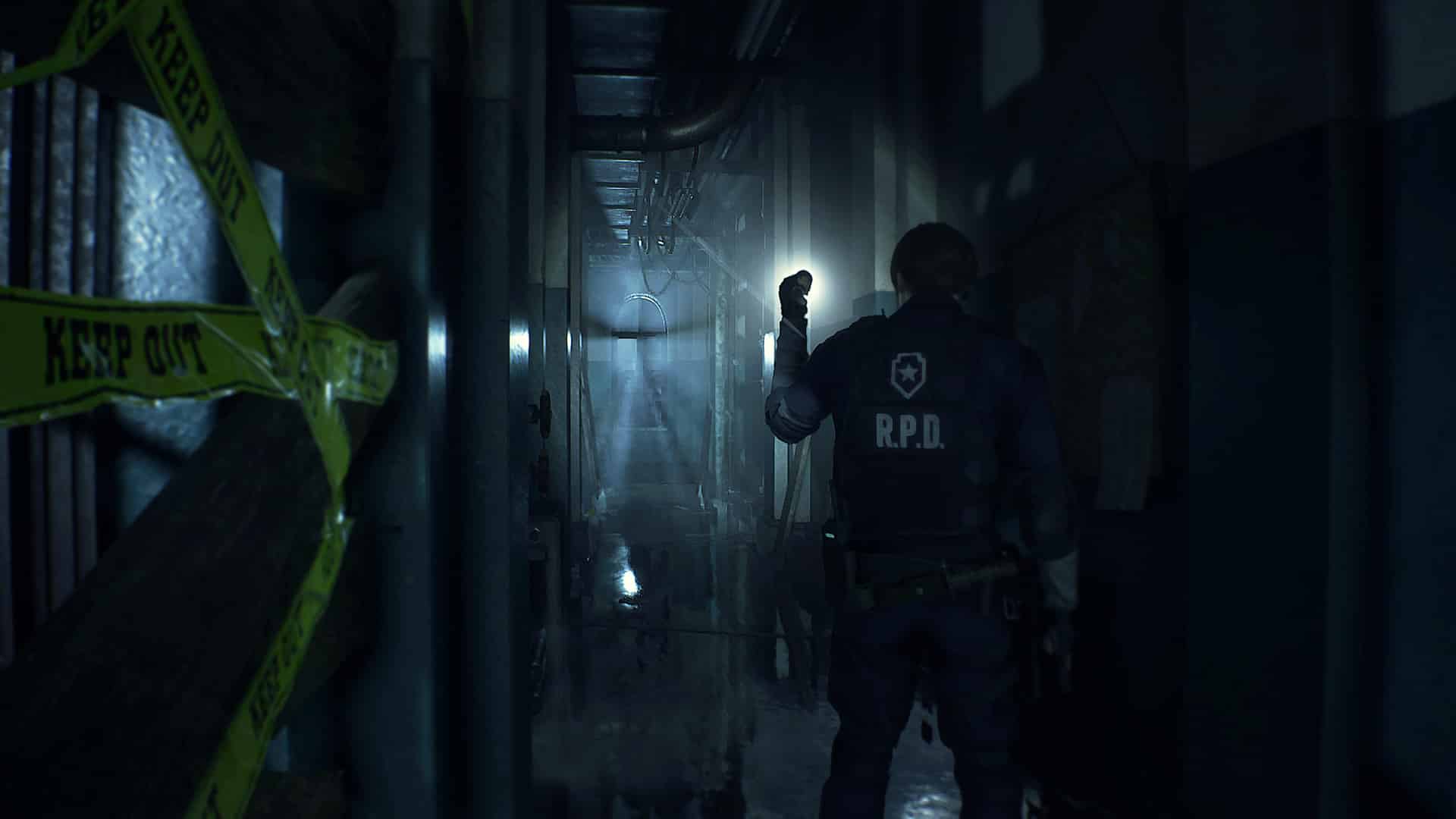

As a current-gen game, the Dead Space remake, powered by EA’s Frostbite Engine, looks and plays exactly how you’d imagine: high-quality textures and with impeccable 3D audio pieced perfectly with dense atmospherics and environments draped in mood-perfect lighting. Under these special effects, the core game is still there, and its core gameplay loop is relatively untouched. Dead Space likely plays as you’d remember it in 2008, and still boasts the strength of its single-location setting.

A few key elements of the game, however, have been retouched, and appear in the form of relatively minor ‘quality of life’ changes. Pay any attention to the game’s marketing and you’ll notice there’s been a concerted push to make the game feel more dynamic. This dynamism is emblematised in the ‘Intensity Director’, a system that controls the pacing and spawning of enemies to keep the tension high and encounters fresh. Elsewhere, extra puzzles have been added in the form of circuit breakers, often forcing you to decide if you want to progress through your next room and subsequent enemy encounters with either the lights or oxygen off.

While welcome additions, the effects of both features are largely overblown – chalk it up to marketing hype. To my eyes, there’s nothing in the ‘Intensity Director’ that separates it from any other horror game’s enemy spawn system. The circuit breaker puzzles are sparse and slight, and don’t impact the experience enough to write home about.

The most significant change the game makes is the restructuring of the USG Ishimura from a series of discrete levels to an entirely explorable and seamless ship design. Traversal to disparate parts of the Ishimura was previously routed through the ship’s internal tram system, which the player would route their way to at the end of each of the game’s dozen levels. In the remake, the tram is still running but becomes a far less rigorous form of traversal, more appropriately functioning as a fast travel point to allow you to go back for any missed collectibles.

The Ishimura’s new ‘seamlessness’ is an integral part of the game’s effort to feel more expansive than the original. It’s key to not only the ‘necessary’ (or at least ‘expected’) level of elevation involved in contemporary, post-RE2 remakes, but in satisfying a more general requirement that new games balance reliability with novelty, that they deliver both repetition and innovation within the same package.

As seamless as the Ishimura may now be, its many, many corridors, elevators and dark rooms blend into a single gestalt, and backtracking is not only laborious in action but takes away from the immediacy of the game’s horrors. A new security clearance system locks you out of certain rooms early on, forcing you to backtrack to find missing weapon upgrades when your clearance level is eventually high enough.

It’s a feature that feels like it’s been added to justify an otherwise uninteresting ‘seamless’ Ishimura. It’s a post-Dead Space game design function that has been retrofitted to bring it more in line with games that it was actively working against, with its naturalised HUD and progressive waypoint system.

More Context! More!

The refurbished Ishimura is in service of adding ‘extra context and polish to the experience’, as John Linneman of Digital Foundry suggests, enthusiastically fleshing out the game’s new tech in his technical analysis. Certainly, ‘extra context’ and ‘polish’ are the game’s twin driving forces. In the remake, there’s a sense that elements from Dead Space 2 – the more-popular sibling – are being retrofitted to the original game (as Matt Purslow from IGN has suggested). In the sequel, for example, the remake’s zero-gravity rooms are fully traversable spaces that no longer force you to do a funny point-to-point space jump.

The most obvious addendum is that Isaac is now fully voiced, as he is in later entries, with actor Gunner Wright returning to the role. No longer the silent protagonist (sans heavy breathing and aggressive grunts) whose voicelessness added much to the original’s lonely and unspeakable horrors, Isaac is now equipped for extra-terrestrial banter with his ill-fated crewmates.

The unspeakable horrors are no longer unspeakable.

Wright is perfectly fine in the role, and when speaking while suited up often sounds bizarrely like latter-day Tom Cruise (even if the continual yelling for your wife, Nicole, is an early Cruise affect). The game’s additional dialogue and rapport work to give a broader context to the narrative, an attempt to spell things out further. One of a few newly added side missions tasks you with tracking hologram recordings of Nicole diagnosing the ship’s many issues, all the while fleshing out a history of Isaac’s relationship with her, and giving broader emotional context to your interactions. It’s true that this time around the Ishimura, I had a better understanding of where I was going and why – but I missed the original game’s opaqueness, that feeling of drifting almost robotically from one end of the ship to the other, from disaster to disaster.

Inevitably, the remake largely feels well-trodden – its core horrors are well-known, mapped out in walkthroughs and trophy guides, or still floating around in your head, a decade and a half later. Hindsight has been added to Isaac’s new list of abilities: it’s as if the characters can sense they’re in a remake and know just as well as you what they’re getting themselves into, upon their arrival on the Ishimura. (Final Fantasy VII Remake does a similar thing, though much more interestingly, making it explicitly part of the text.)

Ambiguity, dread, and helplessness are all supplanted by clear directives and amicable rapport. There’s an omniscient feeling to the remake that (almost) betrays or gives away the organic sense of discovery in the original. Dialogue makes sure every action is spelled out, logically justified and realistically motivated, lest you forget this is a silly space video game.

With respect to the much-maligned, well-memed, ‘it really makes you FEEL like X‘ turn of phrase in videogame criticism, I find there’s a kernel of truth to it in regards to the original Dead Space. In its sluggish movement, coarse animations and crippling framerate, you feel, as or like Isaac: out of your depth. You absorb (an approximation of) the feeling of being a futuristic space engineer completely new to the horrors of the Ishimura.

Compared to its technically refined remake, the original game feels messy, rough, and makes you work to carve your way through it. Environments feel hazardous in a way that’s almost sanitised in the remake. There’s a kind of stylised ambience to this game, a sheen of frailty or vulnerability stretched over a seamlessly working and connected engine. The original game’s ambience is drawn not only from its aesthetic features, but in its technical instability, the way its slow, clunky, and stuttery performance add great effect to its desolate narrative and fight-for-your-life gameplay.

Playing Dead Space at 60 frames-per-second feels far too smooth. At a 4K resolution, there’s too much clarity in the image. The PlayStation 5’s haptic controller feedback is serviceable, but it feels wrong when I shoot my Plasma Cutter, and my framerate doesn’t drop drastically, relieving the weapon of its once-hefty kick.

Unreached Potential

Matt Purslow at IGN also likened the remake to a ‘director’s cut’ that, instead of recutting old material, completely refilms its material on brand new sets. If Dead Space is akin to any kind of revised version, it’s far from the special editions that George Lucas infamously made for his Star Wars films, and much closer to something like Disney’s twenty-first century trend of ‘live-action’ remakes of their beloved hand-drawn animated films, where artistry is relegated to technical achievement, and photorealism is followed as an (always out of reach) end-goal.

A more medium-appropriate comparison would be The Last of Us Part I, a remake which similarly updates a PlayStation 3 game (albeit with a more complex history of remastering) into a PlayStation 5-level experience, vying, like Disney’s The Lion King remake, for a photorealistic new version that works to replace the original or render it obsolete by comparison.

The discussion becomes, as Naughty Dog developers plainly assert in their ‘Honoring the Original’ featurette for The Last of Us Part I, about this idea of an ‘unreached potential’ of the original that was hindered by hardware, about remedying technical limitations, about achieving things they were – in retrospect – ‘unable to achieve’ in their original game.

When all is said and done, the logic becomes: ‘Now that everything we couldn’t do has been done properly, why would you go back to the original version?’

That is – if you ever had a choice. Remakes like this aim not only to honour, but to eclipse their original versions as their old hardware burns out and big studios maintain their disinterest in preservation. There’s a mercenary capitalist drive unpinning these decisions that makes the remake a little nauseating. At what point is it appropriate to draw a correlation between EA, Visceral Games, Motive and the reanimated corpses wandering aboard the Ishimura?

Don’t take me for a fool: I agree with Master of Horror John Carpenter that ‘E.A.’s refurbished’ Dead Space is a great game, one that I will play through at least two more times (for the New Game Plus and Impossible difficulty trophies). Like many, I hope they follow in Capcom’s footsteps, and continue to remake the entire trilogy.

Despite this, I feel the Dead Space remake offers a different experience, one that sands down distinctive characteristics of the original in emphasising a mode of horror that’s far less lonely, and much more gory. Flashier, but less tactile – where the once-unknown ‘horrific truth’ of the Ishimura has been restrung with new tech, its hallways polished before being re-bloodied.

In the end, it’s a new product made for seamless consumption.