The world changed in 2020, in every aspect. Our individual lives changed. Our jobs changed. And across the globe, various industries had to reckon with a new normal: coronavirus-induced lockdowns, manufacturing delays, rising shipping costs, and the knock-on impact of loneliness and isolation. The board games industry was one of the hardest hit, with every aspect of tabletop manufacturing, production, playtesting, and component creation being affected.

At the same time, board games experienced a massive rise in popularity – creating a vast imbalance between the ability to supply them and soaring consumer interest. More people wanted to buy board games. They wanted to back Kickstarter projects, take part in multiplayer tabletop sessions, and invest in the future of the industry. Inadvertently, this contributed to mass production blockages, as worldwide lockdowns in manufacturing capitals – largely, in China – delayed new tabletop games, and forced a global industry slowdown.

Since 2020, countless backers and buyers have waited patiently for news of the latest board game projects – major titles from publishers like CMON, Flyos Games, and Serious Poulp. Likewise, independent game developers have suffered delays, as limited production capacity has meant sliding down the pecking order for batch manufacturing.

Read: Tabletop gaming is adopting digital tools for a brighter future

Board game developers in Australia and overseas are currently reckoning with these changes, with renewed patience, higher budgets, and optimism now necessary to push new board games out the door.

The pandemic has been a ‘double-edged sword’ for designers

‘One way or another the pandemic has been transformative for everyone; as a game designer it has been a double-edged sword,’ local Australian developer Christopher Ng told GamesHub of the mounting challenges of the pandemic. ‘On one hand, the pandemic focussed me. Prior to 2020, I spent my time exploring with every cool mechanic that crossed my mind. During the pandemic, I found myself with the time and perspective to realise what I really wanted to do was create a single great game that really mattered.’

‘Conversely, the pandemic created one of the least favourable conditions for board game production I could imagine. The lack of in-person playtesting meant exclusively online playtesting, which while an amazing tool, is only an approximation of the tabletop experience … Furthermore, the coronavirus has reshaped culture as a whole and it has been impossible to avoid that shift affecting the tone of Aethermon.’

Aethermon: Tower of Darkness, one of the PAX Aus 2022 Indie Showcase winners in the Tabletop category, is a co-op roguelike that tasks players with capturing monsters, and making them fight in intense, attack-based battles. It’s directly influenced by the work of Ken Sugimori on Pokemon, but adapts more strategic elements via creature skills and combination plays.

Ng has been developing the game for several years, and has implemented vast changes to his creation process in an effort to circumvent global circumstances, and better account for bottlenecks – including the rising cost of manufacturing goods. Specifically, paper.

Paper is the heart and soul of board games

‘The shipping crisis has so many causes: increased demand for goods out of China, rolling lockdowns reducing capacity in port, worker shortages affecting trucking and overland freight, bad luck in the Suez, one-off events like Brexit – it has kinda been a perfect storm,’ Ng said.

‘The paper shortage shares many of its causes with shipping crisis: the costs of shipping affecting the price of paper (and the raw wood pulp), the increase in global demand for paper products and paper packaging for non-paper products, and the closure of paper mills around the world during Covid-19. Ethically sourced paper has further become more difficult to source due to timber from Russia and Belarus being declared “conflict timber” by the FSC and PEFC.’

According to Ng, quotes for paper are now at least twice as expensive as they were five years ago, when production on Aethermon began. There also seems to be a lack of progress in addressing these concerns, with no relief currently on the way for paper costs.

With many Kickstarters charging customers for expected costs pre-pandemic, there is now a major disconnect between the funds acquired by developers early on in the creation process, and the funds needed to complete development. In some cases, this has led to creators asking supporters for additional funds, or to pay extra for shipping.

‘Often these projects collect funds for producing a game years before they need to ship the game to their supporters. These projects likely costed international freight at around US $1,500 for a 40ft container; at the peak of the shipping crisis the average cost of shipping a 40ft container around the world was 10x that,’ Ng explained.

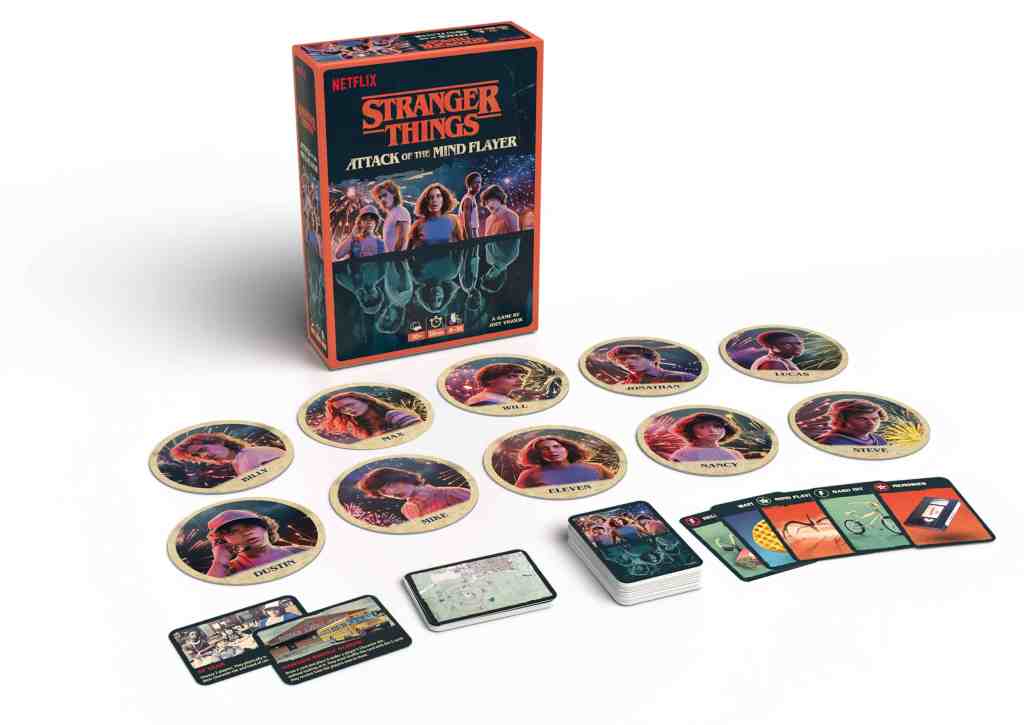

Joey Vigour (Chaosmos, Battlestations), a game developer and designer from the United States, has experienced similar challenges, despite designing many of his board games with the backing of global brands, like Netflix. His latest title – Stranger Things: Attack of the Mind Flayer – has just landed in Australia, months after its release in the United States.

According to Vigour, it wasn’t his only project that faced delays, thanks to shipping and paper manufacturing costs.

‘Costs to manufacture internationally went up, and USA/Europe-based manufacturers didn’t even try to offer competitive prices to win new business,’ Vigour explained of his experiences during the height of the coronavirus pandemic. ‘Paper/cardboard supply chains became limited. Container ship transport (logistics) fees went up dramatically. Every company blamed a different part of the supply chain for the problems.’

Vigour’s journey to getting one of his latest projects published was a wild one – with several milestones, blockages, and pivots along the way.

‘The military locked down one of my factories in Shanghai by force, and my preproduction samples went missing. I shipped my games to Los Angeles, then had to redirect my shipment through the Panama Canal to Florida because L.A. and Long Beach’s ports were congested. I ended up hiring a trucking service, and because the truckers were on lockdown or on strike, I had to ship by train,’ Vigour explained of the complex manufacturing process.

‘Multiple shipments of mine had to be written off due to a train robbery, and an Amazon warehouse that burned down for unreleased reasons. To save money, I started packing, shrink-wrapping, and shipping almost all my orders personally.’

According to Vigour, the United Kingdom and Europe also presented major issues to this manufacturing journey, with imported goods now garnering major tariffs which make it difficult to turn a profit in the region. Inflation in the United States also contributes to these bugbears, with the euro-to-dollar exchange rate losing Vigour ‘around US $10,000 in royalties in the last two years.’

Kickstarter has yielded frequent success for Vigour in the past, with many of his projects hitting the six-figure mark, thanks to enthusiastic crowdfunders. But with rising shipping costs in regions like Europe and Australia – particularly at the time of launching his recent project, Monsters and the Things That Destroy Them: The Dead – it’s becoming more difficult to offer ‘friendly shipping’, and attract wider, global audiences.

‘It’s hard for me to offer “friendly shipping” because warehousing costs at my fulfilment centres also went up,’ Vigour explained. ‘My fulfilment companies used to charge by weight only. When the shipping calculation methods changed, I had already charged the shipping. I undercharged 1000 customers by about $30 each. I’ll let you figure out the math on what that will cost me … I’ll just evolve my business model until I find something that works better.’

Indie board games have suffered the biggest changes

According to Steve Dee of Tin Star Games, who is currently working on roleplaying and narrative adventure game The Score, another PAX Aus 2022 Indie Showcase winner, these changes disproportionately impact indie board game developers, as the modern cost of manufacturing is extremely difficult to absorb and overcome.

‘It’s calming down now, but the costs of shipping quadrupled or more. If you’re running anything but the largest board game companies, you cannot absorb that much of a price increase,’ Dee told GamesHub. ‘So much of this industry – and so many others – is held together by trying to squeeze barely tolerable prices out of every single step, so there’s any money left at the end, and as soon as any step in that breaks down, the whole equation breaks down.’

‘I think we’re all more aware of that fragility. It might become cheap again to ship worldwide, but companies might not want to start offering it cheaply again – because what if that doesn’t last? It might be easier to just stop shipping to Australia. I’m old enough to remember when we bought everything from America, and paid a friend to mail it to us.’

According to Dee, this shipping and manufacturing process is particularly difficult for those in countries without robust manufacturing hubs. While China is the world’s largest manufacturer of board games, there are also local hubs in regions like the United States and Europe, which are viable for some designers.

In Australia, the only real, affordable option is to have board games manufactured in China – which is where many of the bottlenecks now lie, as lockdowns continue and manufacturing capacity is reduced, despite renewed industry in game creation.

‘Unless you’re printing an enormous amount, you want to print in China and ship from China,’ Dee explained. ‘People are exploring what we call the “local printing” option, but that’s only viable in huge hubs like the US and Europe – and only for enormous print runs and enormous sales. For anything short of CMON (Marvel United, Zombicide), down to the simple designer-owner crowdfunder, China is the only option.’

That option is looking less viable as the pandemic continues, however.

‘Covid caused six months of ports being shut down, and goods not leaving shipping crates. So, quickly the system collapsed. Imagine a sushi train where bowls aren’t coming off the track to be washed up. So, food can’t go in bowls. So, food backs up in the kitchen, and so on.’

‘Previously, shipping costs were fairly flat because you were paying for the labour to move things into the next available crate. Now as your weight goes up, you pay more, because space has to be found. That’s destroying economies of scale … companies have gone broke because they already promised low shipping costs.’

While Dee says he and his team have always tried to stay small, to take the fewest risks possible, his latest project still has major obstacles to climb.

‘We have always tried to stay small and take few risks to avoid over-extending ourselves, but [the pandemic] confirmed for us that wherever possible, it’s generally better to make digital products and leave printing to the customer,’ Dee said. ‘The Score is going to be tiny – but even with that, our sticker shocker was big. We had to raise prices, and also just realise we were going to make less even, assuming we fund.’

Despite this, Dee believes the coronavirus pandemic has inadvertently presented bright opportunities for the growing industry – for its creatives, and its players.

There is a brighter future for board games on the horizon

‘If customers don’t mind higher prices, it could lead to better situations for gaming companies because current prices are based on extremely slim margins for companies and designers,’ Dee said. ‘We’d also like to pay people better for every step in the chain.’

‘In other words, games have been too cheap compared to their cost of manufacture. Nobody likes paying higher prices of course! But if prices rise, it’s good for the industry. You can think about your dollar going further to keep companies going and designers designing.’

Rising awareness of these costs, and an increase in enthusiastic players aren’t the only hidden benefits of the coronavirus pandemic. While the situation overall seems dire, it has led to an unexpected reinvigoration of mainstream tabletop gaming, and opportunities for the creatives designing board games.

For the Quokka Bros, Jonathon and Anderson Cheung, the coronavirus pandemic came with as many celebrations as challenges. In the solitude of lockdown in Australia, the brothers were able to work together to create their own fresh ideas, and designed several board games inspired by their experiences.

‘We’re clearly a product of the coronavirus,’ Anderson Cheung said of creating board games for the first time during the coronavirus pandemic. ‘For us, Quokka Games was established during the pandemic. If it weren’t for lockdowns, we wouldn’t have come up with our first game Carry On.‘

‘We were talking about gamifying the packing mechanic, because that was the most dreaded part of travelling. A lot of other businesses and ideas were also established during the difficult times. Some people had a lot more times on their hands, while other people lost their jobs and were looking for alternatives.’

As online communities grew – including via Zoom, Kickstarter, Discord, and Tabletop Simulator, the team at Quokka Games was able to find their core audience and share more of their personal, intimate, and life-inspired games. With each of the three games – Yum Cha, Carry On, Dirty Laundry – focusing on relatable aspects of living, Quokka Games was able to find a unique niche that brought people together in tough times.

It also led to the team being invited to overseas gaming conventions, and local ones in Australia.

‘We saw firsthand what having our own booth and panel discussion could achieve. The boost in traffic, fans and audience that we experienced could have never been achievable on our own,’ Cheung said. ‘It is quite evident that there is a new demand for tabletop games. What we are suggesting is that a lot of people have found us through PAX … Our hope is, Australia can seize this opportunity and keep this connection with the world strong, for this opportunity can slip away if we ever revert back to the old normal.’

A shift towards digital tools enabled this growth, and became a beacon for the Quokka Games team, even as manufacturing and production issues hampered game production. While the team, like many other board game developers, has experienced plenty of difficulties, it’s clear the coronavirus pandemic hasn’t just reshaped the board games industry for the worse.

Amidst manufacturing shortages, rising paper costs, and shipping slow-down, there is still hope for a brighter future, forged in the midst of major complications. In future, there is a world where board game manufacturers are able to overcome bottlenecks, with the aid of players who have a deeper understanding about our changed world – and how the pandemic has directly impacted shipping lines, work capacity, and the efforts of designers.

These are the players who’ve kept the torch of board games shining over the last few years, connecting online and in more intimate groups to play together. Adaptation and iteration have birthed a more connected board games and tabletop industry – with more accessible communication and refined tools for connection.

Likewise, designers have grown tougher – making harsher choices, pivoting against global circumstances, and deploying new forms of creativity for better-designed and more interesting games, awaiting a patient audience.

Designers and players have learned incredibly difficult lessons in the pandemic years – as have producers and manufacturers. There’s hope these disparate parties can come together to foster an industry that’s hardier and endlessly more creative in the years to come. While there are still prominent hurdles to overcome, there is light at the tunnel’s end.