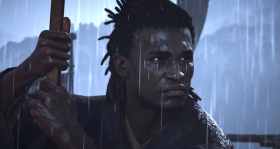

What does it mean to tell an Australian story? It’s a question that weighs heavily in the minds of the Drop Bear Bytes team. Based in Torquay, Victoria, and led by Studio founder Craig Ritchie, the studio’s debut title Broken Roads is due out this year, a grim narrative adventure that looks part Mad Max, part Fallout, and offers a new perspective on Australia, post-apocalypse.

In Broken Roads the players are tasked with travelling, surviving, forming communities and making moral choices in their fight for survival. The game is set to blend classic turn-based tactical combat with a rich narrative to explore the complex ethical questions that inevitably arise when you’re fighting for your life.

Leanne Taylor-Giles, the game’s narrative lead, describes Broken Roads’ distinctly Australian setting as a rarity in commercial games; she calls the game ‘a celebration of our unique culture, that we hope will give people more insight into what it really means to be an Australian.’

READ: Why do the elves in Dota have Australian accents?

It’s a rich creative goal – and one that requires real care to do right. Despite their love of genre, Drop Bear Bytes are focussed on making a game that reflects the complex reality of Australia, without relying on stereotypes. Representing life in this country is more than just vegemite and prawns on the barbie – this land is home to the world’s oldest living culture. Aboriginal peoples are the world’s first creative technologists, whose expertise is spread across hundreds of Indigenous nations.

To this end, Drop Bear Bytes hired Indiginerd founder Cienan Muir, a Yorta Yorta and Ngarrindjeri writer, events producer, cosplayer and lover of pop culture, who ran the country’s first IndigiCon in 2019. Now, he’s working with Taylor-Giles to provide both an expert perspective on the narrative treatment of Aboriginal characters and Countries, as well as giving creative input of his own. Muir describes the game as ‘a moral and ethical look at a world conquered by the apocalypse’ that will actively resist stereotypes in its characterisation of Indigenous cultures.

I spoke to the team about Broken Roads’ approach to telling a multifaceted Australian story. This interview has been edited for clarity.

Craig: I first met Cienan, very briefly, after a panel discussion about Indigenous representation in games at PAX 2019. I wanted someone close to the space who could help out with authentic, respectful representation. Drop Bear Bytes had already been fortunate enough to receive the support and guidance of Anthony Hume from the Narana Aboriginal Cultural Centre, but having someone engaged within the team in an ongoing capacity as Cienan is now was much needed.

READ: Cultural integrity and Indigenous collaboration on the Innchanted soundtrack

Cienan: After fully understanding the game and the unique nature of it, I knew it was something I wanted to be a part of. It was also that I saw the team’s desire to do things right, which gave me a good understanding of just how I could make an impact and how my voice would be heard within this space.

Game development roles can look really different from project to project, especially in small teams. What do the narrative roles on Broken Roads look like?

Leanne: Because we are a small team, designing the narrative means touching storytelling in every aspect of development. We work closely with the art department, our sound effects designer and composer, and our level designer to make sure each place, person, and prop does what we need it to do, and that we’re getting story and world ideas from as many people as possible.

Cienan: As an Aboriginal, it is tough to watch a film or play a game where Indigenous characters, stories and representation aren’t done in the best way. Instead, stereotypes, tropes and racist myths are often relied on in film.

I’ve always been a huge advocate for telling our stories respectfully, and ensuring that we are involved in the process when there are Indigenous stories being told.

Cienan Muir

My role within the team is providing that critical eye where Indigenous Countries and characters are concerned. It also gives me a chance to get creative and let my own stories have some influence.

Cienan, you’ve been in the games space for a while, but this is your first game development role. What prompted the choice to move into game development?

Cienan: There’s amazing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people doing amazing stuff in the game world, whether in development or narrative. But there are few pathways and little opportunities for our people from a STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, Mathematics) perspective, including for those wishing to work for games companies.

I’ve always been a huge advocate for telling our stories respectfully, and ensuring that we are involved in the process when there are Indigenous stories being told. I thought this was a great opportunity to dip my feet into the world of narrative within the gaming world. A large influence for this has been examples of Indigenous people being involved in game narrative from other parts of the world, such as the game Never Alone (Kisima Inŋitchuŋa), [a narrative game that was developed through a partnership between the Cook Inlet Tribal Council in Canada, and E-Line Media].

I hope to see many other Indigenous people being offered opportunities in the gaming industry, but equally as important, a strengthening of STEAM educational platforms for our communities.

Indigenous artists are creating some of the best film, literature and TV, but they seem to be less common in this games space, despite Victoria’s thriving games scene. What do you think can be done to make game dev more welcoming and appealing to Indigenous artists?

Cienan: I think it starts from high school. There’s a crucial need for STEAM-focused pathways, and Indigenous young people must equally be supported to pursue those goals. Game companies must understand the impact of creating a supportive and nurturing environment. In understanding that you have reach and impact as a company, you should also understand that you have the responsibility and privilege to be able to offer unique spaces for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

What’s unique about games as a storytelling method? Are there unique possibilities that games can offer Indigenous creatives, and Indigenous stories?

Cienan: I think games have more of an impact on society as you are actively in control of an avatar, which can reflect on yourself, when you encounter moral choices and ethical questions.

As comic books had, and continue to have, an impact on us as a society, I think games are capable of reflecting ourselves in relation to the world around us.

Leanne: The power of video games lies in experiential learning… this approach is so effective, especially when it comes to moral or social issues. When done well, it has an immense capacity to transform the player’s worldview, encouraging new or different behaviours, and opening new pathways to places the player may never even have dreamed of.

Craig: There’s nothing quite like it in terms of providing the freedom to go through a story in multiple ways, with branching paths, and even multiple endings that react to player choices. As for unique possibilities for Indigenous creatives, well, I’m keen to see where Cienan takes us!

(This article has been republished since its original publication.)