The 30th of October 2022 marked a decade of one of the most interesting Assassin’s Creed games to date. A game that bucked series trends in several ways, weaving a tale that has become more perceptive of the times since, and one that has just as much to say mechanically as it does narratively. It’s an Assassins Creed almost lost to time itself: Assassin’s Creed Liberation.

Released on the ill-fated Playstation Vita in 2012, before being ported to PC in 2014 and rebranded as downloadable content (DLC) for Assassins Creed III, Liberation sits at odds with the franchise as a whole. As a benefit of being developed as a smaller-scale side project for Ubisoft teams in Sofia and Milan, it was somehow allowed to stray from the formula already firmly cemented in the mainline games.

For one, the protagonist is a woman – a revelation in itself – and she leads the charge through a concise 8-hour campaign. These are two things the main games – with their increasingly bloated, endless worlds and female optional-at-best central characters, still have not matched to this day.

Ten years later, playing through Liberation’s bite-sized missions, designed for quick handheld play sessions, feels like a breath of fresh air for the series. Small-sized open environments, rather than the giant, anxiety-inducing giant playgrounds that take hundreds of hours to cover, allow for a level of intimacy and recognition all but impossible to imagine for the likes of the most recent entries like Origins, Odyssey or Valhalla.

In the eyes of many, Liberation falls short of the big-budget experience expected of one of the biggest gaming franchises in the world. But if you take a closer look, and pay just a little more attention, it becomes clear that the swings Assassin’s Creed Liberation takes are far more interesting than just about anything else an Assassin’s Creed has done to date.

Fake News and the Warping of History

While the narrative Assassins Creed Liberation tells is perfectly serviceable on its own – digging into the secret political deals between the French and Spanish in pre-America Louisiana marks a favourable setting for some Assassin Vs Templar shenanigans – it’s in the how that this experience gets at broader, somewhat prescient themes about how we digest media on a daily basis.

The path of protagonist Aveline isn’t as simple as ‘Assassins good, Templars bad’ – at least, as it’s presented to the player.

It’s important to remember that in 2012, the meta layers of the overarching Assassin’s Creed narrative were kicking into full swing. Abstergo, the main antagonistic force in the series’ ‘modern-day’ timeline, was more than just a vague corporate entity serving the ancient order of Templars – it was also an entertainment company creating popular video games for a ravenous public audience

A full year before Assassin’s Creed Black Flag signalled a move away from the original modern-day arc featuring the character Desmond Miles, Liberation was already laying the groundwork. In the fiction, the events of Assassin’s Creed Liberation take place in a ‘historical video game produced by Abstergo’.

But if the truth doesn’t suit your agenda, why stick to the facts?

If you play through Liberation and stick explicitly to the script, the game ends in a way that favours the Templars – making them look like the ultimate ‘liberators’. But, if you choose to engage with the person (or program?) called ‘Citizen E’, extra scenes will be revealed to you as part of the ‘true’ story, which as you can imagine, swing things back into pro-assassin territory.

It’s a simple but effective lesson in critical examination, and one that isn’t so obvious in our current media ecosystem. In 2012, the idea that you shouldn’t just believe what’s presented to you might have seemed obvious and benign. In 2022 – particularly if you have someone in your life fully bought into Fox / Sky News, Qanon, or the moral panic topic of the day – the foresight is alarming.

In the fiction, Abstergo created Assassin’s Creed Liberation as a game that reflects real historical events, but twists them for their own means – not only to ‘create a more entertaining product’, but to serve as messaging advancing the agenda of the corporate interests behind it.

But don’t let the truth get in the way of telling a good story, hey?

Mechanical Storytelling

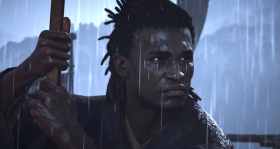

For as out there as the explicit narrative is, it’s what’s implicit that really makes Liberation a standout in the series. Where almost all other Assassin’s Creed games use setting, tools and protagonist to ground the player in a certain time period, Liberation places you not just in the body of a bi-racial woman in 18th century Louisiana, but uses its systems as storytelling tools in and of themselves.

Liberation’s defining mechanic is Aveline’s ability to swap between three ‘personas’ – a lady, a slave, and an assassin – each offering different modes of interacting with the world around you. Aveline’s lady persona allows for a more diplomatic approach, gaining access to restricted areas without getting in trouble, but is very restrained mechanically – she holds very little weaponry and can not climb. Dressing as a slave, Aveline can blend in very easily – unnoticed by the powerful, due to their disregard of someone they see as lesser – and is able to climb, but still unable to carry a full arsenal. Finally, the assassin has access to everything Aveline could need – but is automatically suspicious in the ever-vigilant eyes of the town guards.

Even ten years later, it remains one of only a few examples of a world reacting to who you are rather than just being window-dressing for the playground you’re currently inhabiting.

Walking down a back alley as a lady may result in you being accosted by thugs. Moving around as a slave draws the least attention, with one important caveat – you must act how society expects you to. Start climbing a wall in front of someone, and you will immediately arouse suspicion. Presenting as an assassin, Aveline’s mechanical possibility is expanded – that is, she is the most empowered she can possibly be – which, without Aveline even lifting a finger, makes her suspicious by default because of how she looks.

This element of freedom via mechanic is most prominent with a tool gained around halfway through the game: the slave whip. Once taken from a slave master, Aveline can use the whip for two purposes.

Firsty, it can pull an engaged enemy closer to you, throwing them off balance, and allowing you to strike them when their guard is down. Secondly, it is used in the environment as a traversal tool – a grappling hook used to leap distances Aveline could not previously. A tool once used to subjugate, now becomes a tool for both equalising the battlefield, as well as expanding literal freedom via Avaline’s traversal potential.

For more on these ideas, we recommend you read Evan Narcisse’s piece that digs into the concept of Black power fantasy.

A Forgotten Gem of Assassins Creed Canon

Earlier this year, Ubisoft attempted to quietly shut down various online components of many of its older games. This rippled out to Assassin’s Creed Liberation’s Steam page, noting the game was to not only be delisted, but will soon become completely unplayable, even if you already owned the game. The confusion around this messaging was eventually resolved – the game is still purchasable and playable, albeit with some minor DLC removed. But it’s a timely reminder that these experiences, even ones only a decade old, are ephemeral – particularly if we leave them to fade into the past unnoticed.

Despite being relegated to a side entry in the Assassin’s Creed mega-franchise – and sadly often at the bottom of series-specific ‘best of’ lists, if it appears on them at all – Liberation is one of the few Assassin’s Creed games that had the freedom to experiment with storytelling, both through its mechanics and meta narrative.

It’s not only worth your time as a player, it’s worth studying for its attempts to build something genuinely interesting and different – not lost to the annals of history.

You can still find Assassin’s Creed Liberation on PC via Steam and Uplay, and in physical formats on Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, and Xbox One.

GamesHub has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content. GamesHub may earn a small percentage of commission for products purchased via affiliate links.