When one of my primary school teachers pitched Dinosaur Discovery to the class as a ‘video game’, I’m quite sure I scowled and crossed my arms. I had already beaten a few King’s Quests, maybe even an Ultima, so word puzzles (shoehorned into a story) just seemed like schoolwork on a screen to me.

After decades of furrowing my brow at ‘edutainment’, I’m surprised to now be appreciating ‘games that could be amazing in the classroom’. If I was still a high school music teacher, Amberial Dreams would have inspired me to run to the nearest science teacher and yell, ‘Let’s do a cross-disciplinary project on momentum and melodic improvisation,’ with the game as its driving content, of course.

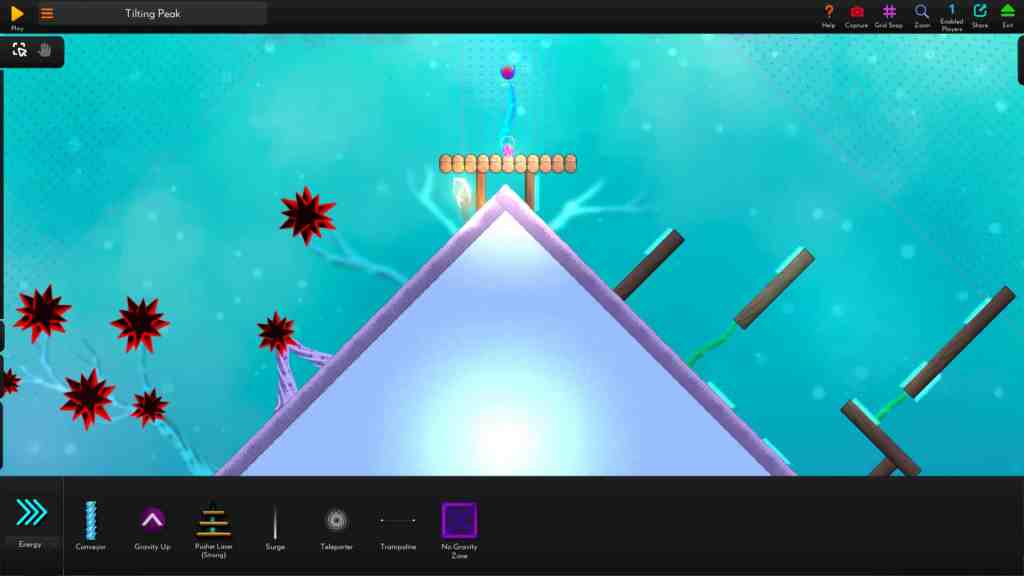

Amberial Dreams is a 2D platformer, but without a jump. You propel your ball, left or right, hitting objects in the correct spot, at the correct speed, based on their physical properties.

So, using a bubble to reach a platform requires assessing its relative bounciness and aiming within a useful arc. It’s possible to alter momentum mid-flight, but good planning makes for orderly play.

Designer Cuauhtemoc Moreno, says, ‘It feels like pinball, except you are controlling the ball itself.’ And yes, that’s exactly how it feels.

Colliding the bubble creates a percussive ‘pop’, and platform collisions create a metallic major third, tonic, or some other interval that interacts pleasantly with the background music. Your journey is not only pinball, it’s also one long musical statement.

In its early access form, there are 58 campaign levels to play, with more promised. With several game pieces at your disposal, including collectibles, breakables, levitators, escalators, sentinels, spikes, and more, I found many (definitely not all) of the levels I tried were straightforward enough to complete, though certainly at a significantly slower speed than par.

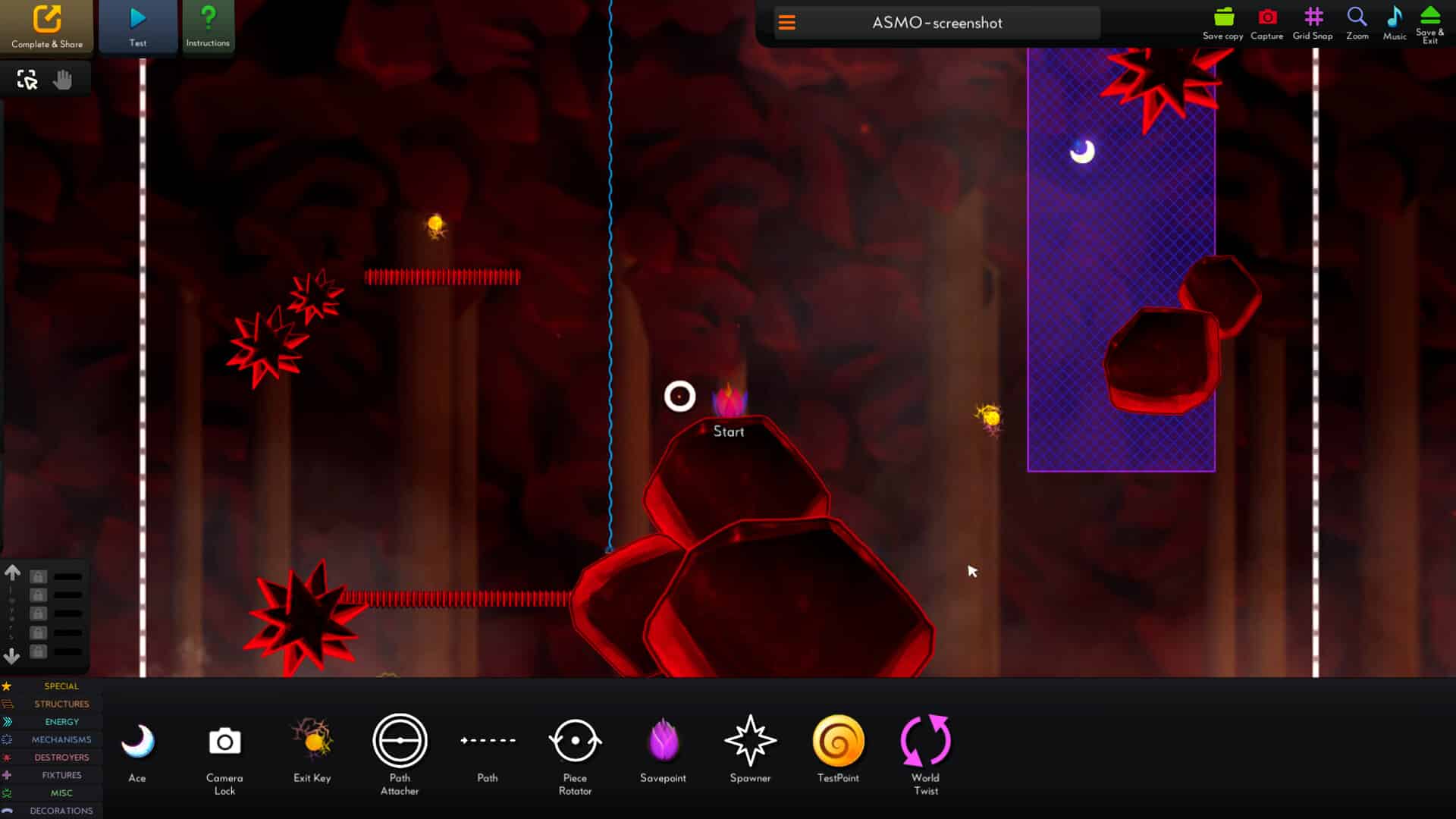

There are some clever user-created levels, too, and I particularly enjoyed ‘Upside Down in Spider Den’, which riffs on a gravity-switching mechanic. The level editor is also extremely intuitive. You can choose from around 60 game pieces, under headings like ‘structures’ and ‘destroyers’, drag and drop them into place, then test. Moreno says that there have been 200 user levels created so far.

Rather than aiming to make a challenging puzzle with the level editor, I found myself creating an instrument, or maybe, a kind of ‘performance chamber’. I noticed the default background musical loop was built on a descending guide tone line, with gentle glockenspiel and pizzicato strings, before a heavily processed beat was layered in. I made platforms of wood, to match the muted initial tone colours, then metal columns and trampolines, so I could play collisions louder, over the percussion.

I jammed thoughtfully around my level for a surprisingly long time. Bubble solo? Why not?

I know exactly the kind of listening and analysis assignment I could set for Amberial Dreams’ premade levels, as well as a composition and performance assignment students could complete via the level editor. What assignment might a science teacher also tie to this game?

So, am I finally ready to accept the inevitable marriage of games and education? Recently, at PAX Aus, I had trouble prising my 15-year-old son away from Gubbins, which is explicitly, and unapologetically, a word puzzle. Dinosaur Discovery upset me because it was a word puzzle in a game’s clothing – ignore that Sierra’s adventure game text parser taught me to spell. Amberial Dreams is a game first, but surely also the delight of teachers and students alike.

You can find Amberial Dreams on Steam Early Access.