After a year of working full time in the games industry as a narrative designer, I’m still wrapping my head around the fact that I’m now a game developer.

I came to game dev following over a decade in media and academia, reviewing thousands of games and writing – by my estimation – over a million words about games, for what amounted to surprisingly little money. In January 2021, I jumped over to the other side, joining the narrative team at Mighty Kingdom in my hometown of Adelaide, South Australia.

What is a narrative designer?

The role of a narrative designer can vary depending on the studio and the project. My job has involved writing outlines and scripts for chapters in an ongoing narrative service game, as well as briefs for art and animation assets, character bibles, and a lot of documents that amount to pitches to the rest of the design team: ‘hey, what if we tried this?’ I also sometimes hop into Unity to design cutscenes and fix bugs, and I have a lot of planning and review meetings. It’s a big change from playing the new Call of Duty, and deciding whether to score it a 7 or an 8 out of 10.

This is not a role that exists inside every studio.

Many of the narrative designers in Australia and New Zealand I’ve met are freelancers or work short-term contracts on a game-by-game basis. I am extremely fortunate to have the job that I have at a studio where the role and importance of good narrative design is considered central.

Read: Your games career as a: Narrative Designer

It’s also one of the many roles in game development that isn’t fully understood by game enthusiasts. While my job involves a lot of writing, it’s not all a matter of scripting dialogue: it involves a lot of long-term plotting, discussing how narrative can integrate with gameplay, and making sure that the narrative is balanced just right against every other aspect of the game.

It means coordinating between different departments to make sure the narrative is working in conjunction with every other part of production. I’ve seen comments online from people who do not believe that writers and narrative designers count as game developers in the same way programmers do, and that’s fundamentally wrong. If you’re lucky enough to have a big enough team size for diversified roles, there’s no question that each person, and each team, is making contributions of equal merit.

In the year since I started this job, my relationships with games, with writing, with the industry at large have changed completely. It’s a dream job for me, a perfect fit for everything I value. But it’s also a job that took me a long time, and a lot of soul searching, to realise that I wanted.

Making the leap to game development

I made the jump for a few reasons. For a few years, when asked how long I’d been doing that sort of work, I’d reply “too long”. Despite this, emails to PR representatives I’d met before about major releases would still often prompt replies asking who I was, exactly. I’d reached a point where I was finally earning a full living wage from writing alone, but I found myself less satisfied with my work and feeling more adrift and invisible within the wider industry – and when your job is to attract eyes to your words, feeling invisible is awful. The work became harder to take seriously and I found that I was no longer enjoying myself.

More importantly, I’d come to understand that the role of a narrative designer was a perfect fit for the kind of work I wanted to do, and the person I wanted to be. The shift from games media to some other games-related position is something of a rite-of-passage in Australia, for those who don’t leave games behind entirely. Many members of the media have ended up as streamers, or in PR, or as developers. But I always felt that it was writing that I really loved; games just happened to be the subject I understood how to write about the best.

I wrote my first freelance article about games in 2007: a retrospective about Bubsy for Hyper magazine (summary: it was a good game, everyone is wrong about it). By 2010, the magazine had made me a “senior writer” (which was a nice title with, on reflection, few tangible perks beyond the suggestion that the editor liked me), and I’d become games editor of Mania, Next Publishing’s magazine for kids. At the same time, I accepted a scholarship to study a PhD in game narrative, and my freelancing ramped up considerably.

In the ten years that followed, I often felt like I was working towards something, with no clear picture of what that was, exactly. I pushed back against the idea that I might want to move into game development one day. I did not think I had it in me, or that my skills would transfer. In my head, the developers I interviewed were committed to a kind of magic that was beyond me, even as I found myself increasingly burned out by the games I was playing constantly for work. Even the bad games felt like miracles.

My journey from there to game development is a long one, although it feels like I walked down a lot of dead ends along the way. The PhD didn’t pan out, but my thesis was eventually published after being retooled into a Master’s project. I hung around the university, teaching classes and working on research projects that were fitfully rewarding and beefed out my resume. When the time came to apply for a narrative designer role, I had the thesis ready to prove I’d given the area some thought (I would not recommend games academia as a good entryway to narrative design, even though it played a big part in my own story).

Perhaps it goes further back than that, though. I remember the first time I ever saw a video game being played in someone’s house. My mum would get her hair cut at a friend’s house, and I remember watching their son play what I now think must have been Golden Axe on a Mega Drive. The simple fact that this kid could directly control what was on the screen blew my mind in that foundational way you can’t recognise at the time. My reverence for games started that day and never left me. The idea of actually making them long seemed ridiculous and impossible.

The first few months

Jump forward to January 2021, and the first time I opened Unity on my work computer. I’d tinkered with game maker software before – a few unfinished Twine projects, some Unity tutorials – but I’d been very upfront throughout my application process about my lack of real experience in game development. I was keen to learn, but also secretly very nervous that I would fail every challenge placed in front of me.

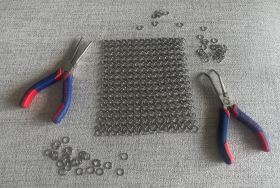

I’d just learned about my project’s process for cutscene blockouts: rough early versions of cutscenes that might not have every asset in them yet, but which feature all the right characters, basic movements, camera shifts, dialogue portraits, and provide a starting point for polish. As I learned of all the tools available to me, I felt overwhelmed, slightly panicked that my Unity layout did not look the same as a colleague’s.

The first scene I blocked out was a simple one-character cutscene: a man is searching a manor ground for a dog that has gone missing. He walks around a patio deck, looks panicked, considering places the dog could be as the camera follows him. There’s a dramatic zoom in on him as he contemplates his options.

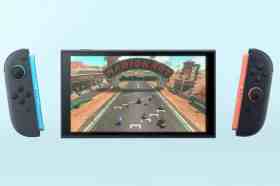

That cutscene I worked on is available deep into the ninth chapter of Ava’s Manor. If you play the game and get up to it, know that’s the point that my contributions kick in.

The feeling of completing my first blockout – of doing work that I knew would appear in the game – was an enormous rush. It was the same feeling I had back in 2007 when I saw my name in print for the first time next to an article I’d written. Two moments in my life where I’d made something I was proud of, something unlike anything I’d made before, and which came together quickly and were approved by the professionals I was working with. My first year of working as a narrative designer has been defined by these little moments where I’m amazed by how good it feels to make a game.

The biggest surprise, for me, is how much the skills I developed as a freelance critic and journalist map onto my work as a narrative designer. My experience at adapting to different styles and forms of writing has proven extremely helpful, and I consider myself a decent writer after so many years of needing to convince dozens of editors that I can string a sentence together.

More than that, though, being a critic allowed me to play so many games, and to really think about what makes them work. Design is often an act of bricolage, collecting a variety of experiences and influences together into something new. With hindsight, I’m willing to admit that a huge part of the appeal of being a game critic is the deluge of free games: I have played a huge number of games and have been influenced by all the great storytelling I’ve had the pleasure of experiencing.

Every game is a miracle

After years of looking at games as a connected outsider, seeing how the sausage is made is more exciting than I anticipated. A lot of the stuff I wrote feels trite compared to the simple joy of writing a scene with some emotional weight to it. I never imagined the joy of asking the art team for a particular asset and being presented with a proper masterpiece, or getting access to a beautiful new animation, or coming up with a very silly joke and then getting it through multiple stages of approval so that it ends up in the game.

And importantly, every game still feels like a miracle. Developing games, and understanding more about how they’re made, does not demystify them. No matter what, being able to move the character on the screen is always going to be magical to me.