You don’t get Heavenly Bodies without Galina Balashova.

Born in Russia, 1931, Balashova has been referred to as ‘the architect who drafted the space race’. She began her career in 1955 as a residential architect, tasked with removing architectural decorations considered ‘bourgeois’ or ‘decadent’ by the USSR government of the day.

It was only a year later when things changed, and Balashova was swept into the globe-spanning, decades-defining space race between Russia and the U.S. After accepting a Senior Architect position at OKB-1, the Soviet Union’s Experimental Design Bureau, Balashova began by designing living quarters for employees of the Russian space program, but eventually transitioned again, joining the design teams for the Salyut, Soyuz and Mir space stations.

The difference in perspective Balashova brought to the Soviet space program was immense, as she zeroed in on the fact that cosmonauts would actually be living aboard these crafts. Specific care went into orienting someone for a zero-g environment; painting floors and ceilings different colours to communicate the intended orientation of a room, and the layout of equipment throughout a space.

In a 2015 interview with MOTHERBOARD, Balashova, who at the time was 84, reflected on her career, and the compelling contrasts that came from having such an artistically and aesthetically-minded individual put to work on one of the most militarised and high-stakes projects ever seen by the Soviet Union.

‘I love my job since striving for harmony and determining the correct dimensions — still to this day — fascinated me, but to put it briefly, space has never appealed to me the same way architecture does’, Balashova said at the time. Much of her work remains in orbit around earth to this day.

Dissonance of experience is core to upcoming Australian-made game Heavenly Bodies: earth & space, gravity & weightlessness, art & science, intention & outcome. Much like Balashova tried to find some middle point between the familiar apartment and the foreign space station, Heavenly Bodies tries to use that same grey area to create puzzles and obstacles out of seemingly simple tasks, which honestly feels like an extremely human compulsion.

‘What’s really interesting is — because her work was so grounded in building apartment blocks on earth — nobody had actually gone up into space yet, so her take on it, and her ideas around what she thought cosmonauts might need or want is quite interesting,’ Joshua Tatangelo told GamesHub of her influence on the game.

‘Because no-one could say if it would work or if it wouldn’t. You look at a lot of her designs and it feels like gravity is still there, there’s this sense of orientation – you sit on a chair, and the roof is above you.’

‘Very homey’, offers Alexander Perrin.

The birth of 2pt Interactive and Heavenly Bodies

Tatangelo and Perrin met at RMIT University in Melbourne, brought together by study in the Bachelor of Design/Games, and encouragement from Jennifer Lade, a Senior Lecturer in RMIT’s School of Design.

‘It was essentially a playdate’, admits Tatangelo when recounting his and Perrin’s meeting as organised by Lade. ‘We had really similar values,’ says Perrin, ‘from a practice and aesthetic point of view – and, yeah, it was a long time ago, but the goals and values still align.’

Perrin and Tatangelo connected almost immediately. From Perrin’s view, it was Tatangelo’s nature to appreciate detail, combined with his technical proficiency— aesthetics, but aesthetics that justify themselves mechanically — which was key to fuelling their working partnership. Tatangelo describes Perrin’s work as ‘analogue, traditional, illustrated; stuff that had this kind of heart, which didn’t look contrived, or just coming from something that he’d seen,’ he says.

‘You can’t fake that stuff, and I think we probably both spotted it in each other.’ Soon afterwards, 2pt Interactive was formed.

After years of establishing themselves with client design work and small scale games, the origins of Heavenly Bodies began to form. The initial desire, according to Tatangelo, was to solve the fundamental mechanical problem of movement in space. However, initial prototyping of Heavenly Bodies hit a wall fairly quickly.

The control scheme originally saw the cosmonauts reaching for wherever an analogue stick was pointed using any part of their body, which felt off; and the movement systems felt too loose. Tatangelo tried adding a jetpack, but things just weren’t coming together, and the game lacked the tactile interaction with the environment that makes the final game so satisfying. ‘It was just a complete mess,’ recalls Tatangelo.

The duo decided to shelve the game for a time, but after Perrin gifted Tatangelo a copy of Soviet Space Dogs, a book filled with illustrations and reference material from the early days of the Soviet space program, 2pt had found their inspiration once more.

‘Let’s just give it a month,’ they thought at the time. ‘Let’s just completely absorb ourselves in it; get it looking right, feeling right.’ After a month of steeping themselves fully in developing the game, Heavenly Bodies started to take shape.

Learning to spacewalk

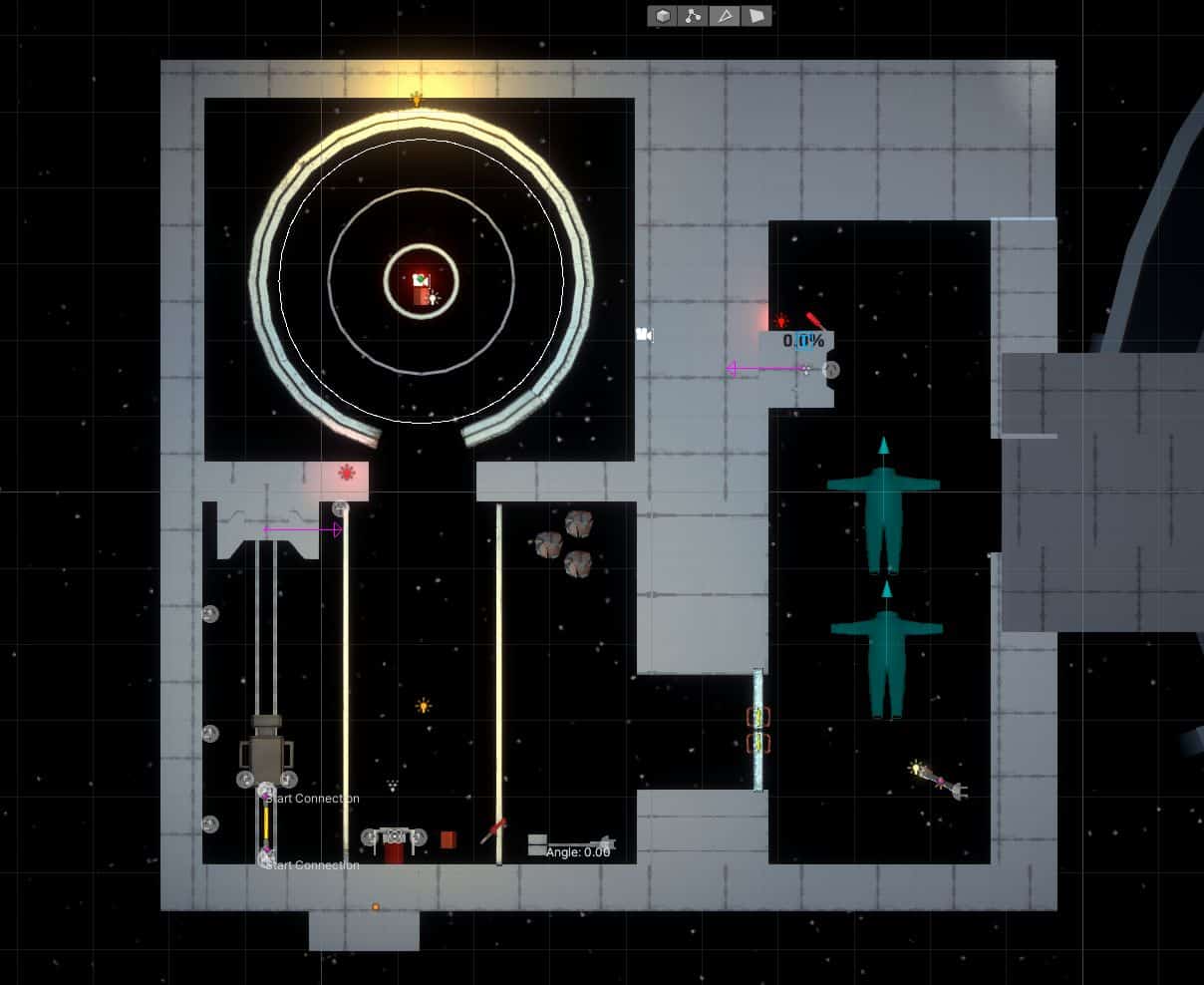

As a game where you navigate weightless cosmonauts through increasingly complex missions around a space station, Heavenly Bodies is an experience which mines joy from movement, like a baby learning to walk for the first time. Moving the left and right analogue sticks controls your cosmonauts’ respective arms, while you can grab items and surfaces using triggers controlling each hand.

With this control scheme, players are expected to construct communication arrays, deploy satellites, and even mine asteroids for scientifically valuable minerals, with everything occurring in a fully simulated environment.

Alongside Balashova’s work from the 1950s and 60s, product and technical illustration more broadly is something Tatangelo points out as a major influence.

‘Technical illustration has been a massive driver and motivation and reference for the art-style. The idea of the handbooks is kind of based on essentially how it works in space, I suppose,’ he says, referencing the hand illustrated reference manuals that essentially act as ‘how to’ guides; laying out the nuts & bolts for each mission of the game as though you were putting together a piece of IKEA furniture.

NASA itself uses a similar concept for its astronauts in space, and Tatangelo recalls watching an interview in which an astronaut explains the concept of a ‘1-pager’ – a single sheet of paper which needs to explain mission critical operations in the most succinct way possible: ‘because when everything’s going wrong and everything a mess, it needs to be concise.’

Heavenly Bodies’ reference guides aren’t just a series of visual flourishes either, as Perrin and Tatangelo wanted to impart a level of expectation onto players, Tatangelo explains.

‘We thought, ‘well, if that’s how it would work for an astronaut, maybe that’s how we should be trying to make the player feel’. Like, here’s this super overwhelming technical illustration, but, you’re the cosmonaut, so you should know what to do with it.’

That’s another distillation of what Heavenly Bodies is trying to do; take extremely complex situations and make your interactions with them both extremely simple and complex in equal measure, and it all rests on the movement system.

‘That was what was so exciting about coming across the movement system in the first place, [it] was like, the most trivial operations, like switching a lever, become these great great feats of acrobatics, and everything feels like such an achievement’

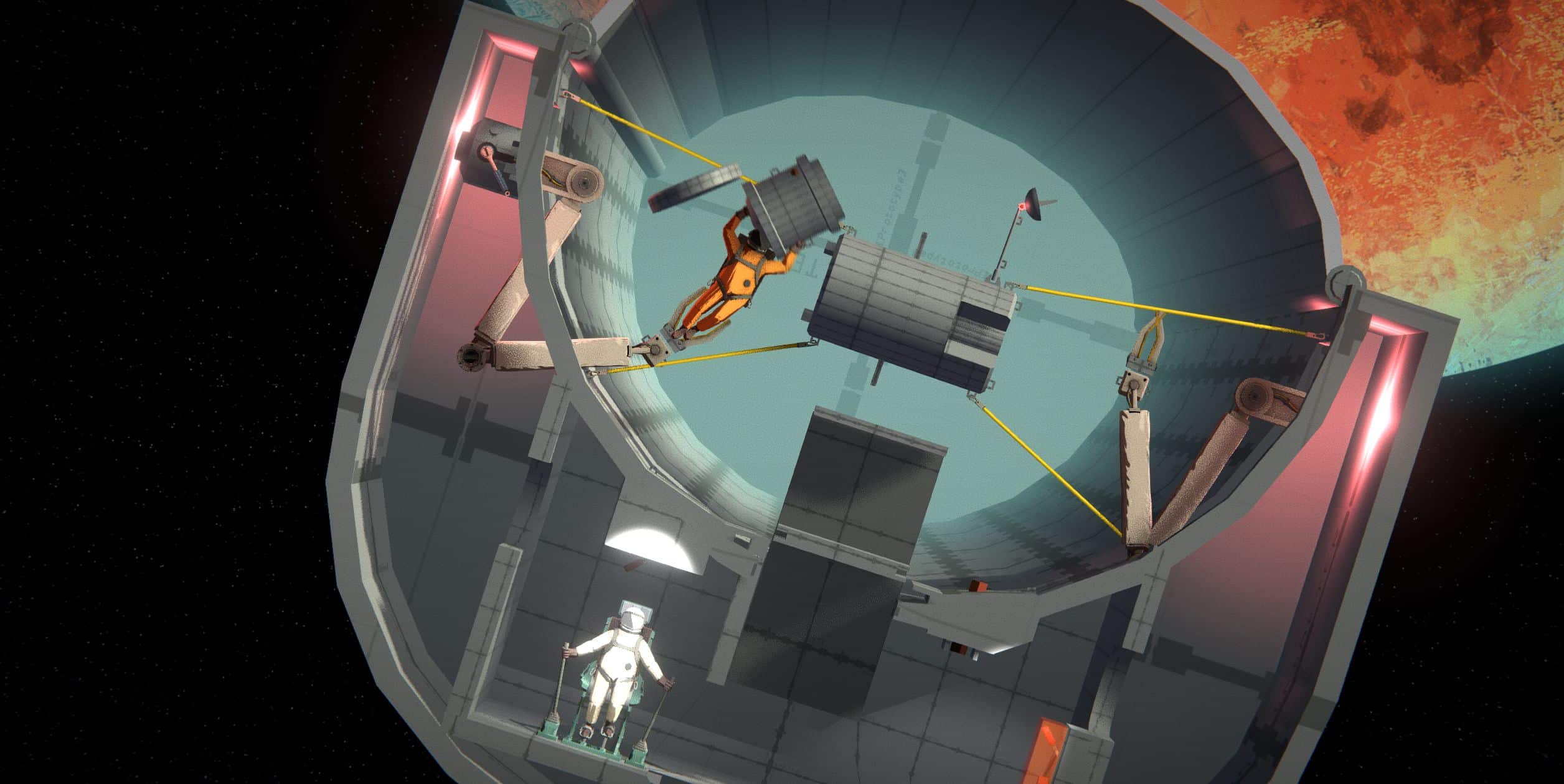

Heavenly Bodies isn’t simply trying to achieve some kind of comedy of errors via physics with a Space Race-era paint job. During demonstrations of the game in the past, Perrin has spoken about the ‘elemental movement of beauty and grace that is often overlooked in the space genre.’

‘The thing that I often reference, or compare Heavenly Bodies to is like a really realistic racing game,’ explains Perrin. ‘Where you’re given this really complex set of controls, and complex set of parameters for how you’re meant to control a body – which in a racing game is a car – and you’ve gotta do just one thing, but what makes it so appealing and what makes it so wonderful even after hours and hours of playing it is just this elegant beauty which comes from the curves and getting an optimum line,’ explains Perrin.

‘When you’re moving about on a space station as an astronaut; if you watch all the videos of the really experienced people up there, they have the same quality as a race car making beautiful lines on a racetrack,’ he says.

‘Heavenly Bodies certainly doesn’t come off as that when you first play it, because your body gets in there and you’re flailing around like a fish out of water, but I can guarantee, after playing it for a few hours, you do start to grasp the affordances of your body, and what your capabilities are, and you start to be able to flow in a really beautiful, elegant way.’

‘It’s still one of these games that are hard to develop because I get so hypnotised watching my character flow through the space… I ultimately want and hope people are able to achieve that same confident and beautiful level of dexterity with their zero gravity body.’

It remains to be seen whether that beauty will translate to players, but one thing Perrin isn’t wrong about is the tendency for games set in space to almost ignore the nature of the environment they’ve chosen, or simply take the clearest threats from them — like a lack of oxygen or spooky alien deities — and ignore the rest, leaving players with the ability to jump higher and not much else. Heavenly Bodies is a refreshing change simply for how interested it is in how it would actually be ‘up there’, and the tactility of the environment.

‘That’s often the thing that will hook us about a game, the way it feels to play or the way it controls; the agency it gives you is where we put a lot of that attention. I think naturally when it comes time to make things, that’s where we put it back out. I think we’re very much about the second-to-second feel of a game. Does it feel good just moving, or getting from A to B?’

Getting over Getting Over It

At PARALLELS 2019, a showcase event curated by Freeplay Independent Game’s Festival during Melbourne International Games Week, Heavenly Bodies was met with praise and — in a surprise for its designers — uproarious laughter, as Perrin and Tatangelo demonstrated the basics of the game and its movement.

‘As you can see, it looks like it’s a comedy game,’ said Tatangelo during the presentation, the crowd already simmering with laughter, ‘but it’s actually not.’

‘Stop laughing,’ followed up Perrin, as he loaded into Tatangelo’s game as a second character, after which both cosmonauts were immediately sucked out of an airlock.

It’s clear there’s a lineage for a game like Heavenly Bodies – as there’s history of physics based games that communicate something to the player through movement systems. Games like Getting Over It With Bennett Foddy, a climbing game where players scale a mountain using nothing but an oversized Yosemite hammer; a game so difficult, users have tagged it with ‘Psychological Horror’ on the Steam Store.

However, where games like Getting Over It are explicitly designed to steep players in failure as a philosophical jumping off point to other topics, Heavenly Bodies takes a different tact.

‘I think where we start to depart from [Getting Over It] is we’re always trying to make sure we’re not trying to do something that is actively punishing, or something that would set you back in a way where you’re just like; “I get what’s going on, but I don’t really want to have to do that again just because the game is making me do it”’ says Tatangelo.

At the same time, Perrin remarks on the undeniable legacy of Getting Over It (which itself finds inspiration in a 2002 game, Sexy Hiking), ‘QWOP and Getting Over It were kind of like proofs that you can have an entertaining game that’s just about performing one arduously difficult motion.’

Heavenly Bodies itself features a more challenging control mode, called the ‘Newtonian’ mode, where the realities of a zero-G environment are on full display. If there’s nothing in your immediate vicinity to grab onto in Newtonian mode, you’re just left flailing until your inevitable demise. You cannot ‘space swim’ in Newtonian mode, to be clear.

‘I think the fact that we’re always making you do stuff with your bare hands is enough of a step apart… it’s just that extra layer of danger, and stupidity,’ laughs Tatangelo.

‘All sorts of occupational health and safety issues,’ concurs Perrin.

It’s clear, ultimately, that Heavenly Bodies is simply filled with love, reaching out in all directions. ‘We’ve always loved the love of space, historically,’ says Perrin as our conversation comes to a close. ‘It’s this mystical, untouchable, unifying hope that humanity has had. Everyone loves the moon, this object that’s out there that everyone can see; everyone can feel together.’

‘That shared magic, for me, has always been the goal.’