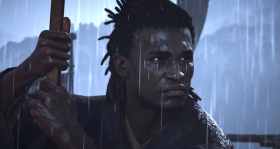

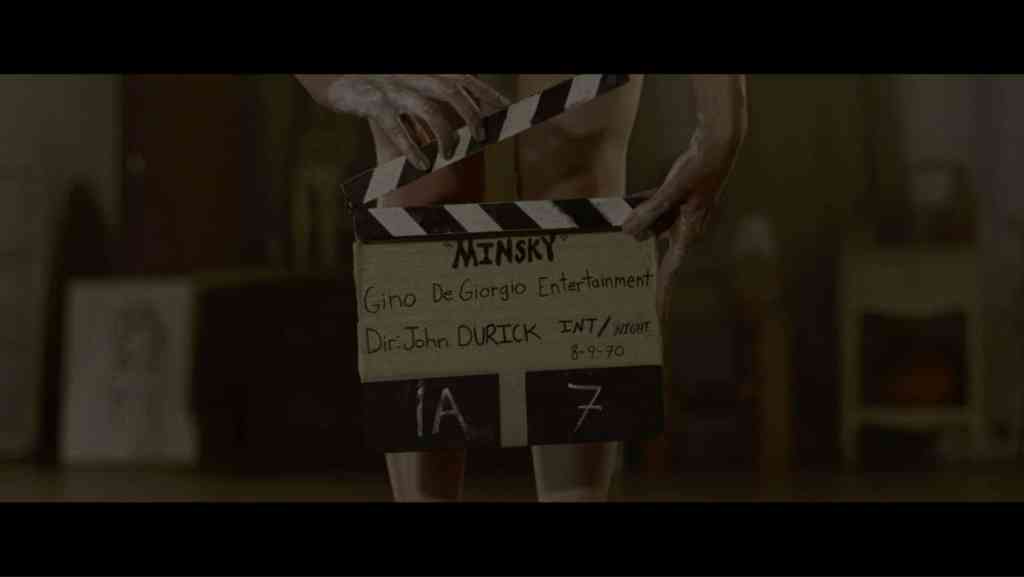

After a stellar year and multiple awards for Immortality – including BAFTA and GDC awards for Best Narrative and Innovation – Sam Barlow and his team at Half Mermaid Productions are working on something brand new. A game that shifts away from the FMV trilogy that has become synonymous with Barlow’s name, and back to the realm of what he calls “proper video games”.

But the ambitious creative ideas and mindset he’s developed throughout work like Her Story, Telling Lies, and Immortality will remain, as will his alternative approach to the game development production pipeline, informed by his experiences working on big games like Silent Hill: Shattered Memories for Konami, and a cancelled Legacy of Kain game for Square Enix.

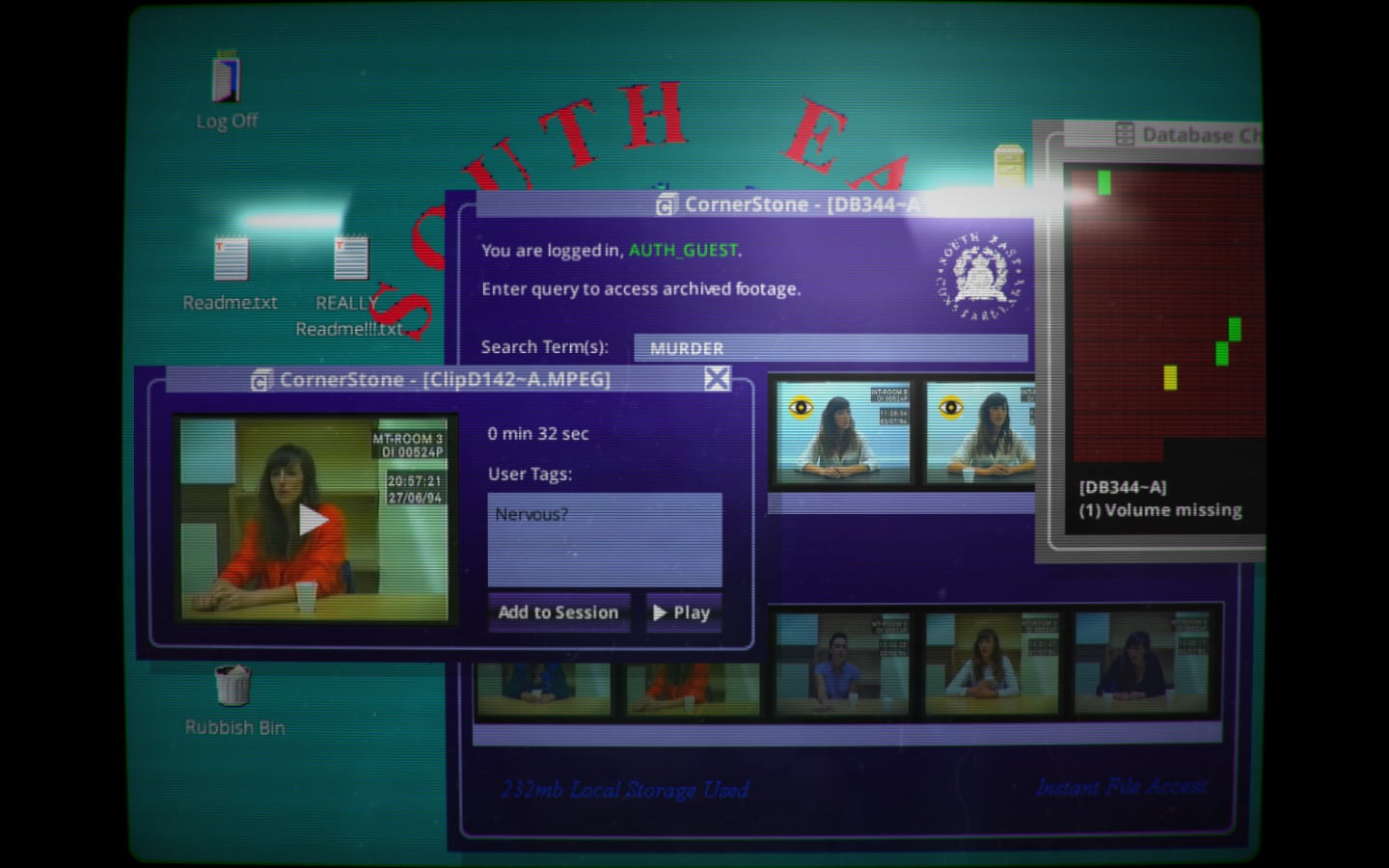

Read: Immortality review – Picture perfect

Ahead of Barlow’s appearance at SXSW Sydney, where he’ll be talking about the potential of storytelling in the 21st Century, as well as looking back on Immortality, he spoke to GamesHub about the new Half Mermaid project, how his current creative process was shaped, and how he perceives video games in the broader screen industry.

You can catch Sam at SXSW Sydney in two different sessions, Making a Mario out of a Moviola and Ushering in 21st Century Storytelling, and a Live Director’s Commentary of Immortality

SXSW Sydney takes place from 15-22 October 2023. For more information, visit the official website.

GamesHub: How’s it going, Sam?

Sam Barlow: It’s going okay. Annoyingly, I’m getting into the grumpy old man years at the point where it’s also like, “Oh, maybe the world’s actually getting worse? Crap.” That aspect is fun. But getting to continue to make weird and interesting video games is fantastic. So you know, swings and roundabouts.

I feel you there. So what have you been working on lately? You can be vague, but I think you’ve been tweeting a bit about working on production documentation, and trying not to play Baldur’s Gate 3?

I failed. [Laughs]

We are making something amazing and ambitious. It’s a whole thing, and this is my return to making a 3D, third-person, character-based video game. But, it’s bringing all of the Immortality stuff with me – all the tricks. So yeah, the thing we’re working on is “a real video game”, which… there’s quite a lot of work.

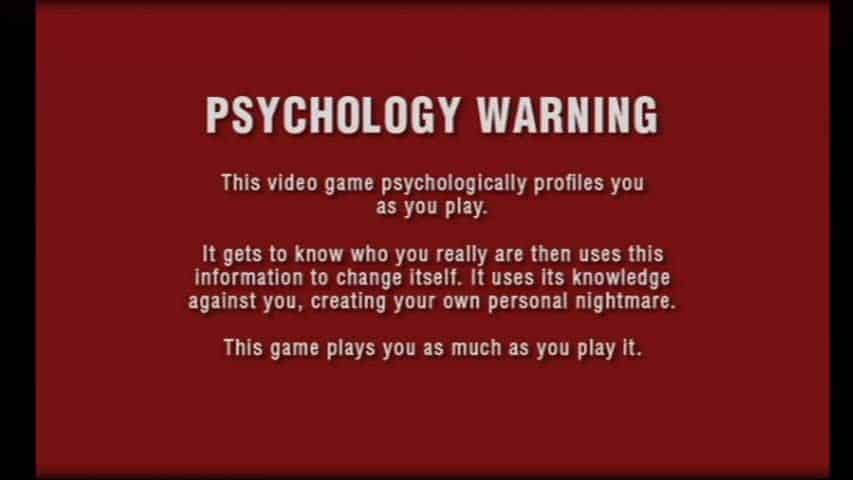

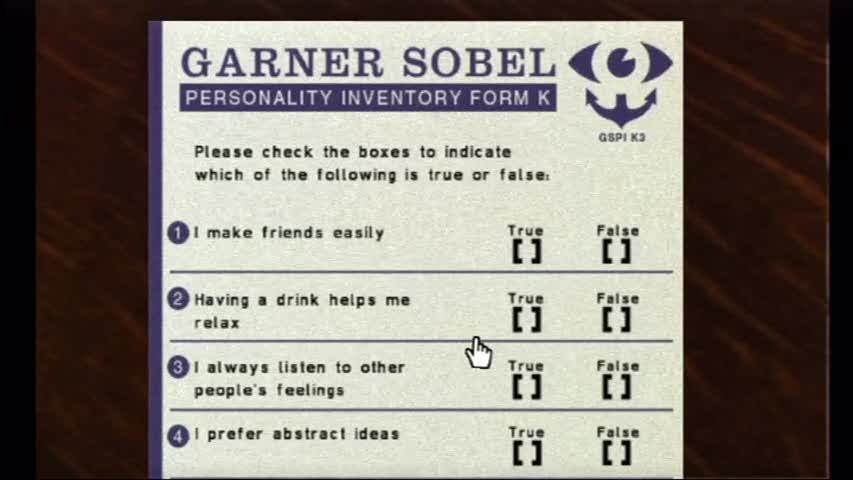

But it’s accidentally – or at least at this point – without this being the design, a very precise synthesis of something like Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, with everything about Immortality. So, how do you take that kind of exploratory, expressive, nonlinear approach to storytelling? The kind of abundance of story that you’re just dumping people into? And what does that look like in a third-person video game?

Oh, wow.

Also, I think it’s been it’s been 10 years now, since I was working on Legacy of Kain, which we were working on for a few years, and got cancelled. So it’s been 10 years since I’ve officially been making, a “proper video game.” And in those 10 years, I got to sit on the sidelines and be like, “Come on, people! Be more innovative! You’re remaking Resident Evil 4 again?! Come on, let’s go!” Which is very easy to say from the sidelines. So this is me going “No, let’s put my money where my mouth is. Let’s see if I can.”

Her Story originally came out of the frustrations from having worked on Legacy of Kain for three years, that being cancelled, and seeing just the state of AAA single-player story games and being like, “Oh, man. Crap, it’s suddenly really hard to make those things.” And by necessity, the rate of evolution is very slow. If you think of a big video game, and it takes four or five years to make, to sign that game you’re pitching it by saying, “It’s kind of like that other game you’ve already played, which was a game that took four or five years to make.” And, you’re promising that you’ll make something like that game, but it will be like 10% fresher and more innovative.

It’s a very incremental kind of evolution, specifically with genres as well. When I was working on Silent Hill, Resident Evil 4 was this interesting moment because it shook things up a little bit, right? The idea of survival horror was so rigid at one point, it was down to people being like “Well, it’s not survival horror if you’re not clicking on jammed locks and collecting medikits.” And if you tweak one of those things, that’d be like, “Oh, is it really survival horror if there’s not arcane locks and weird puzzles?”

The beauty of Resident Evil 4 was going “No, we’re going to radically jump in a direction.” But then what that meant was that everybody started making Resident Evil 4 and that became the new template.

So yeah, this is me trying to be aggressive in pushing something in a bold direction within my means. It’s gonna be really it’s very dark and twisted, and I don’t think there’s anything – touch wood – like it coming out.

You’ve had the luxury of your own personal subgenre for a while.

That was always the challenge. When Immortality was coming out, I would be nervous before big showcases. Like, “What if someone else comes out with this other game about exploring three lost movies?” You know in your heart it’s not going to happen. I think we’re good. Right? I didn’t have to be too worried that we were going to get gazumped by someone else.

But now moving into a space that’s slightly less out there, I gotta try and stop worrying about that. But I think we’re good.

A lot of the onus on bold innovation really has to come from the creator, doesn’t it? There’s always the fear that the audience might not gel with something if you change too much, but you’ll never know unless you really chuck it out there and go for it. People aren’t going to make demands for something they’ve never seen. This goes for publishers and investors too, obviously.

Yeah definitely. So since Her Story, I continually get invited to meetings with Hollywood people. And for a good couple of years, there was a real impetus to figure out interactive TV or movies, where you saw things like [Black Mirror] Bandersnatch, Steven Sodobergh’s Mosaic, and everyone was terrified.

You go to speak to these people, and they had no idea what this thing should or would be. But they knew they were losing mindshare, to social media, to games, and they were like “We need to figure out the interactive game version of a TV show!”

But every time you had these conversations, at some point, you found out they had stopped because they’d be like, “Wow, this is just too risky. This is too crazy sounding.” And they will always say the same thing, consistently, everywhere in Hollywood: “When someone else nails it, then we’ll be ready.”

Read: Interactivity in film, theatre, and games needs emotional connection to work

Like when someone else has to have that first hit interactive TV show, they will be there. And I’d always be like, “But being first is the win!” You want to be the person who makes Star Wars, you don’t want to be the person who’s making the Star Wars rip-off, right?

But it’s so hard at that scale of business to get people to just step outside. Right now, we’re drowning under IP use, right? But all this IP was originally an original idea. It was originally Stan Lee being a maniac. Star Wars was thought to be a huge disaster. Like when they were making Star Wars everyone was like “What is this nonsense that Lucas is cooking up?” And, you know, all these pieces of IP with endless reboots of Indiana Jones and things – if you keep doing this, there won’t be anything left to reboot, like, come on.

The stuff that really captures the zeitgeist is the originality. It’s pulling something like Squid Game out and going, “Oh, wow, that came out of nowhere” and it’s like, “Yeah, [nowhere] is where the surprising things that are able to tap into things come from.” That’s the endless struggle.

So you’re going back to creating a character-focused game. Would you say you’re basically done exploring games that are framed as “player as protagonist”? Or do you just want a bigger challenge?

Without explaining what the [next] game is, it doesn’t feel wildly different to the approach I’ve been taking. On Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, I had this motto which was “The player is not the protagonist.” For me, the way character-driven stories work is if: I’m watching a movie, this isn’t the holodeck, I’m not the character on screen.

I might identify massively with them, you might use tricks like POV shots, or you might create scenarios where I can intensely feel the Jeopardy they’re in. But a lot of the interesting storytelling comes from me trying to get inside their head, trying to understand what people do, and building to a point where the character does something that maybe surprises me, or is maybe more interesting than I was expecting.

There was always a really dumb assumption in games that, “Oh, the protagonist is just an avatar for the player.” And, I would always hear that, especially from publishers in terms of like, “Oh, they’re just basically like a wish fulfilment puppet for mostly teenage boys.”

When we made Shattered Memories, we deliberately created some of the structure of the storytelling, some of the specifics of how things played out, to create a deliberate distance between the player sat on the sofa, and then the character running around on screen.

At the same time, we were trying to make it immersive, and we were trying to make you feel like your actions in the game are essentially being reflected in the behaviour of your protagonist character. We were trying to find this interesting little gap – what is the interesting distance with the player that creates room for really interesting storytelling?

This was something that was there in the three FMV games as well – figuring out what is the player’s relationship to this material they’re looking at. So in going back to a literal, “you push the stick to move a person around game”, I think we still have that lens on things. And we’re still going to use that as an interesting way to play tricks on people

I love to be tricked in games. So you said “we” – this is the same Half Mermaid crew you had with Immortality? I assume you’ll be scaling up?

Yeah, we’re carrying the same small team forward initially, and then there is a bigger ramp up as we start to try and make all the complicated bits and Unreal Engine 5 doodads – all the stuff that I didn’t miss, like sitting in a room and staring at a character’s face and going, “Is the skin rendering good enough? Is the is the weighting on their facial morph targets giving me all the emotion I need?” All that effort.

You must have some feelings about going back into a space where there’s the opportunity for perfectionism, whereas when you’re working with film and video, you take the shot, you do a few takes, and then there’s only so much you can do to it afterward.

Without making myself sound like an idiot, the first time I was working with a traditional decent film crew – Her Story – I basically shot myself. I remember the costume person came up. And we were about to shoot the scene, and they were trying to get me to sign off on a hat the character was going to wear.

I remember my process, and my head was like, “Why do they care so much about this hat?” Then it suddenly clicked like, “Oh, because when we film this, I can’t change this hat!” Like, this is the hat that they’re going to be wearing for the whole rest of this thing.

So much of my brain was ingrained into thinking like, you can just tweak and tweak and tweak, you can remove hats, move cameras, change lights. And there is something really nice about it. Obviously, you lose that ability to tweak. But at the same time, you gain a real focus. Like all the people working on a film set are looking at the same shot at the same time. And so, you can really rely on people bringing their A-game in terms of their craft, to figure out how best to pull off this shot.

Whereas when you’re directing a bigger video game, everyone’s working on different parts of the game. And your job as a game director is to get in everyone’s work, and be the only person that has that global vision over it. And so it’s a lot more running around and a lot more kind of paying attention to things.

I remember reading an article where they said that since blockbuster movies had become CGI-reliant, all of the production problems that you have in video games had started to appear in movies. And up until that point, movies were relatively controllable. You would get a script, you’d agree to a script, you’d agree on a budget, people would go off and shoot things, disasters would happen. Terrible things would happen.

But still, ultimately, you just had to get to the end of the shoot. If the director was misbehaving, you could pull the director, parachute a new director in, knock something out, put it out on video, aeroplanes. Make your money back.

Like, there was a level to how the game was played, where it was kind of controllable. Outside of Kubrick, there was only so long it would take to shoot a movie, practically. As soon as CGI showed up, you did the thing that we have in video games, where people would underbid for the CGI work. People would be trying to use innovative technologies that weren’t quite ready yet. And then you start having movies slip, and you start having movies with ballooning costs.

And this is the key: Like you’re saying, because of the iteration aspect, if you shot a movie in the olden days, and the film company didn’t like it, they might insist on re-editing it a bit, there might be some ADR. Maybe there’d be reshoots, but that wasn’t really done a lot in the olden days. But ultimately, you had that protection against endless meddling, once you went to shoot.

In fact, often, film directors would love to shoot on location, because it meant there was no meddling from the studio. And you’d have directors like Hitchcock, who wouldn’t shoot coverage, he would only shoot the shots he wanted. Because then if people tried to re-edit it or tweak his vision, he’d be like, “I’m sorry, this is all we shot. It’s gotta be like this.”

But as soon as you get to CGI, now you can have Marvel go, “We did a test screening, they didn’t like this bit, we’re going to tweak this scene, we’re going to green screen everybody, we’re going to have CGI captures of all the sets so we can recreate them subsequently.” And they are able to endlessly tinker, which doesn’t always get you to a cool place.

I think sometimes, those really fun, bold movie-making choices resulted from being up against the wall forced to accept a thing or have an awful solution. You know, the idea that you can keep tweaking it and focus testing it as you can a video game, I think has not been a positive. I think it’s made movies more expensive. I think it’s made movies slightly more bland.

So are you afraid of falling into that trap with the next project? You surely must be.

Well, the trick is – as much as Her Story was me going, “Oh, I think games can be different,” and I wanted to push things like, “Can I make a game that’s all about subtext? Can I make a game without 3D navigation? Can I make a game that’s a police procedural about a woman set in the modern world?” The way I made it was also different.

I had this huge frustration working on Legacy of Kain and things like that, where if you’re making a big story game, you don’t have the luxury that say, a screenwriter would have, to just spend some time planning things out in a creative, happy place.

Because what happens usually is: On Legacy of Kain we probably had a 10-page pitch document that got signed off by Square Enix, and we started making the game and immediately, we had to ramp up, because the publisher wanted the game as soon as possible. There’s a lot of game to make, so people are building animations, people are building level grey boxes, and people are designing game mechanics, whilst I’m writing the story.

So it’s very inefficient and painful. And there are all these examples of, you know, Ken Levine throwing out a whole chunk of Bioshock because by the time he finished rewriting that bit of the story, he was like, “Oh, this doesn’t make sense anymore. Throw out all the work you’ve done.” So you get these very painful, costly processes.

What I was doing on Her Story, and then subsequently all the other games, was my version of game script writing – of planning everything out on paper, then creating prototypes that allow you to fundamentally experience the game. Not as a player, but as a creator, I can sit and play these prototypes and get a feel for the structure.

People could look at the way we’ve done those things and go, “Well, that works because you’re making an FMV game, right? Of course, you can sit and create a text, prototype and worry about the story and, and then go and shoot all the live-action footage and then have a game.”

So with this new one, I think we can replicate a lot of that process of really thoroughly planning out the game on paper, and in really simple prototypes. Which is scary how rarely it happens, right? Because they want games as fast as they can, and because there are inefficiencies that work in some people’s favour. I think everyone’s willing to say “Games are iterative,” or “You can’t sit in a room and plan a game in too much detail” or “At some point, you need to just make stuff and iterate and play test and all those kind of video-gamey things.”

But with this one, we’re trying to create something extraordinarily complicated, in the same way that Immortality was complicated in its own way, and trying to front-load that creative exploration before jumping in and making everything. So we’ll see if I can prove my point and extend that to something that looks more like a traditional video game.

Obviously, there are a lot of creators like yourself who are really pushing the boundaries and the medium to do innovative, interesting things. And I think the whole industry wants video games to be respected and be talked about in the same conversations as great cinema and music. Games are making a lot of money, of course, but there’s still this major perception of games as a frivolous activity, like a juvenile pastime. What are your thoughts on that, as someone who’s trying to push things? What do we need to do to change that perception?

I feel some of it is generational, right? I think there’s only so hard you can push without just acknowledging that this will come in time. I think sometimes we lie to ourselves.

I feel like even though games make all that money… you occasionally have cultural moments, right? You’ll have a Squid Game drop, or Barbieheimer, and those are genuine cultural moments. There’ll be some piece of music, like an Old Town Road that will just permeate the culture in a way that even the hugeness of an Elden Ring or a Zelda, or even a GTA just won’t penetrate in quite the same way.

I think that’s partly generational, I think it’s partly the media. All of our politicians are ancient, old, zombie men. Some of the traditional media is still run by ancient old zombie men. But I also think that we should be pushing ourselves more.

It’s funny, there was a Twitter thread of “gamers” being like “Wow, look at Baldur’s Gate. It just goes to show it is possible to make a classic single-player video game, there should be more of these!” Which to me seemed ridiculous, because the thing is that they want is there. Baldur’s Gate exists. But also, we just had Elden Ring, and we just had Zelda, and we just had God of War Ragnarok. There have never been this many single-player fantasy, video games, right? This is a golden age of them.

But then in thinking about that, it was like, “Wow, these are the big heavy hitters. The big cultural touchstones of our medium in the last few years. And it’s all about dudes with swords running around, whacking things.” Which is completely valid. But there is always this weird back-and-forth in games.

You really saw it when they tried to make VR happen. I remember getting the first memo from Valve, when they first were like, “Hey, VR is gonna be big. Here we go.” And the memo said, “Look, there are things that do work in VR and things that don’t work.”

“With the nausea and the control schemes, you can’t make traditional video games so don’t be making shooters and racing games, make exploratory narrative experiences, make things that are more sensory.” I remember reading that memo and being like, “Yes, this is the stuff I want to make! This is so cool. The art is gonna be amazing.” But they very quickly realized the only people forking out 500 quid for a VR headset and a computer with a good enough GPU were the guys that were like, “I want Call of Duty in VR,” right? So then the whole thing pivoted.

I think we keep having that moment in video games where we get we get a glimpse at “Oh, we could really engage in a much broader way with the culture and with people.” But at some point, if you’re still going “Well, who’s gonna buy the brand-new PS5? Who’s gonna buy this brand-new gaming machine?” The people who will always be there are the people who want a very specific thing. And you can always make them happy by giving them the new Call of Duty or a new GTA, or whatever.

So I think there are so many possibilities, and it feels like as much as we do really interesting things, we are not seizing those opportunities. And I think there is a lot of inertia that comes with the complexity and the cost of making video games. That’s how I felt when I made Her Story. I was like, “Ah, screw it. I’m gonna go make something weird on my own.” And I still kind of feel like that.

TV and film are having their issues and the challenges of originality versus franchises. Whenever I had these meetings in Hollywood, the thing that would always make me happy was that as cynical and evil as everybody was there, they all loved storytelling. And they all understood that the thing that was priceless was an original story well told, and they knew from their story development costs, and from everything, that finding those stories is not easy, and it’s a special beautiful thing.

That industry does value things that are original voices, and are radically new and exciting. They’re looking for those things. And we don’t quite have that same kind of thing – not necessarily in the developers, but I think some of the business people in the game side of things, it’s so much easier in our industry to look at the numbers. And obviously, you have like the exponential free-to-play numbers, which are always gonna look sexier than the half-film narrative numbers, right?

So maybe it’s generational, or maybe it will just keep happening. You have generations growing up who spent their entire life gaming. And I don’t know, are we like the second generation now that has been doing that? So they naturally will have more things to say. And that might percolate through the chain.

I’ve got my fingers crossed. So what can people expect from you at SXSW Sydney?

I’m going to be out there enjoying Sydney, which will be very exciting for me, because I’ve only been to Sydney once, and it was hanging out in the Olympic Village doing mocap.

I’m going to come out and bang the same drum I’ve been banging here, of really trying to dig into what 21st-century storytelling will look like. We’ve had the 20th century of broadcast media, which was an incredible explosion and moment for humanity in terms of being able to tell stories to so many people, and create these genuine cultural moments.

But at the same time, broadcast media inherently creates these static stories. You have to have a fixed movie that’s put in a film can and distributed around. And as much as Netflix and people have disrupted things, they haven’t really changed that. They still deliver the same linear show chopped into the same chunks. I think there’s so much room in the 21st century for taking our storytelling, taking all the storytelling mediums we have, and thinking about how we put back in the intimacy, and the individual personal thing that was there back around the campfire. Things that were there back in the days of theatre and oral storytelling.

It’s even more intimate, right? If I play a video game, sat in front of my laptop or on my TV, it’s this connection between me and the game. It’s similar to how books are a bit more intimate, but then if you have a game that talks back to you and has this feedback loop, suddenly it becomes a whole different thing.

I think what I’ve been trying to do in my own small way is point to very classical stories and say, look, here’s how we can make these things more intimate and personal using this technology. So, obviously a show like SXSW where you’re bringing together all these different mediums is a great opportunity to make that plea. To have everyone jump in – not just in the games space, but in the film and TV space, figuring out how we can usefully tell stories in the 21st century.

Sam Barlow will be appearing at the following talks during SXSW Sydney:

- Sam Barlow – Making a Mario out of a Moviola and Ushering in 21st Century Storytelling

Thursday 19 October 2023, 2:00 PM – 3:00 PM - Immortality Live Director’s Commentary with Sam Barlow

Wednesday 18 October 2023, 3:00 PM – 4:00 PM