When The Last of Us: Part 2 was released in 2020, it was negatively review-bombed on Metacritic. The reaction was intensely emotional and largely came from some mismatch between the playerbase’s own perceptions of reality, and how the game presents reality, with much of this conflict centred around the character of Abby.

As a games researcher, I’ve spent time writing and publishing around the player response to The Last Of Us and The Last of Us: Part 2, and though it’s clear that Abby is designed to be a challenging character within the narrative, she also stands at odds with a long history of the ideal feminine that has dominated the games industry. Other than sexualisation, we have seen the development of archetypes like the ‘helpful daughter’, such as Elizabeth in Bioshock Infinite and Ellie in the first The Last of Us.

For many people video games are a way to immerse themselves in a different world, and in my research, I’ve observed that for some players, anything that they notice which is different from their expectations, intercepts and contradicts their feeling of immersion.

I believe Abby was met with vitriol because she challenges players. She challenges ideas about what women should and can look like. She challenges ideas about what women’s bodies can do. She challenges their sense of righteousness and morality. And these challenges can disrupt the sense of immersion for some players.

Caution: This article will contain significant spoilers for The Last of Us: Part 2.

Abby’s Role in The Last of Us: Part 2

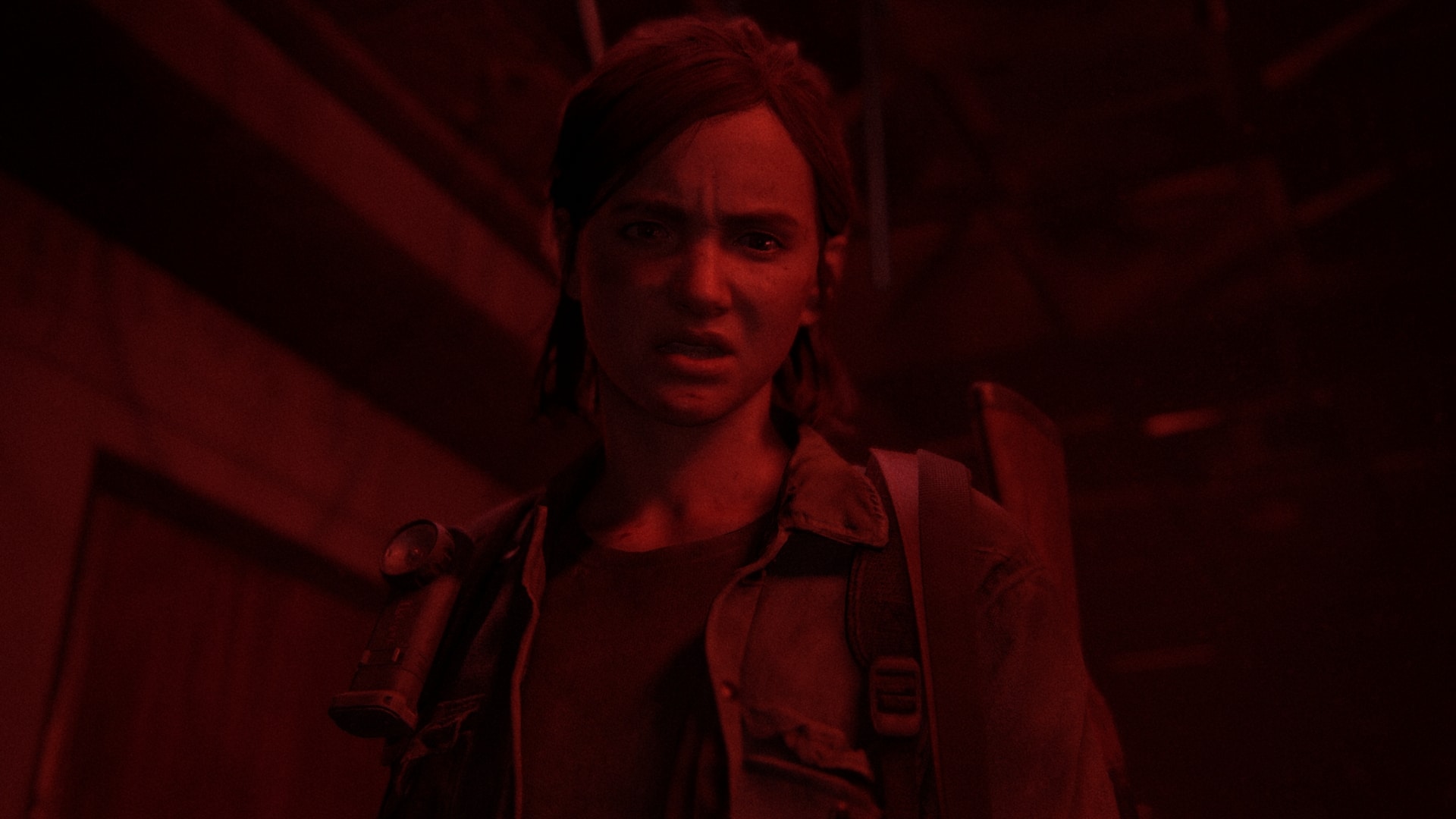

In The Last of Us, you mostly take on the role of Joel and, as in the recent HBO series, he forms a paternal relationship with Ellie. Joel protects and cares for Ellie throughout the game The Last of Us, and when Joel becomes unwell, you venture out as Ellie to ensure his survival. Many positive reviews of the first game focus on the meaningful and emotional connection they forged with the two characters, which reflects the growth that occurs in the narrative. At the end of The Last of Us, Joel kills the people who want to use Ellie to create a cure for the Cordyceps brain infection – a process that would kill her.

The Last of Us: Part II, in contrast, begins with Ellie and Joel in a strained relationship. The situation only gets worse when Abby captures Joel and violently murders him while Ellie watches, and it’s revealed that Abby has done this because one of the doctors who Joel killed in the first game was her father. In The Last of Us: Part II, you actually switch between Ellie and Abby as dual protagonists, with Ellie out for revenge for Joels’ death, and Abby for her fathers’.

Although there are numerous exceptions, video games do have a reputation for fulfilling players’ desires to be a hero, overcoming challenges, or at least establishing some kind of empathy with the protagonist. In The Last of Us: Part II, it’s no longer clear that Joel, who you are encouraged to identify with, and Ellie, who you are encouraged to take care of, are in the right.

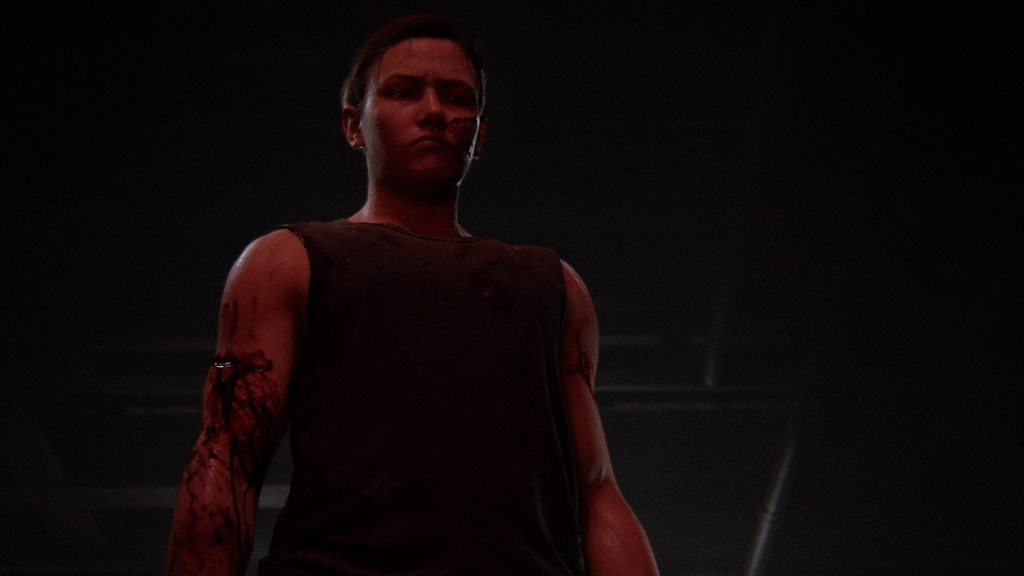

As you take on Abby’s role through the majority of the game, a position you already may be reluctant to take after Joel’s brutal murder, you’re exposed to more and more instances that cause you to understand the character’s perspective and challenge their own ideas of what is right and wrong in the world of The Last of Us. At different points in the narrative, Abby fulfils the role of a protagonist, deuteragonist, antagonist, and anti-hero.

Abby and the feminine ideal in video games

While Abby’s role in the narrative is positioned to challenge players, much of the criticism around her character centred on her physicality. In fact, even before the game was released there was vitriolic speculation that Abby was, in fact, a transgender woman, and she was turned into a meme. Rather, Abby is a muscular woman, and after the games’ release many of the user reviews on Metacritic expressed disbelief that a woman would be able to have her physique. Some also argued that it is unrealistic for anyone surviving in a zombie outbreak to be muscular, suggesting that since people are scavenging, there would not be enough protein to maintain muscles.

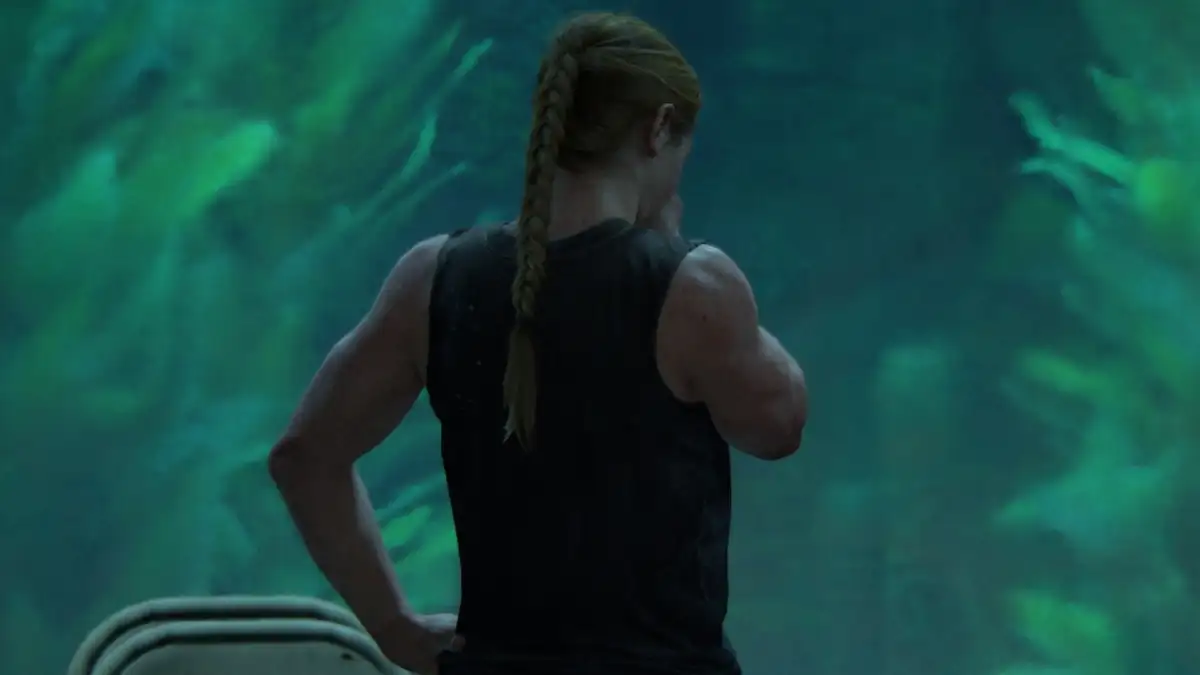

In reality, Abby’s body was mapped from a CrossFit athlete, Colleen Fotsch, a fact publicly shared by Naughty Dog’s Neil Druckmann during the promotion of The Last of Us: Part II. In the game, the players’ attention is explicitly drawn to farmland and animal husbandry in Abby’s community that would provide protein to build muscle. Players also didn’t complain about the male characters being muscular, or the way that they can carry lots of equipment and get shot many times without dying. They were instead being selective about what kinds of realism and unrealism are acceptable.

Some players also made awful comments about Abby’s body, responding with mockery and disgust, especially in relation to a sex scene that occurs during the game. These players appeared to have such a strong conception of what a woman looks like, and is capable of, from their experience with video games, that they rejected any suggestion that challenged their conception of reality. Quite simply, Abby does not fulfil the typical appearance of a strong but lithe video game character like Lara Croft in the 2013 reboot of Tomb Raider or The Witcher 3’s Ciri. While both these characters are nuanced figures with complex storylines, they are designed in such a way that they perfectly adhere to certain beauty standards. Abby does not.

The politics of representation

The suggestion that diversity in representation is only present to be ‘politically correct’ is a message that began to spread in earnest a decade ago, resulting in women and other ‘minorities’ being met with a slew of harassment and vitriol.

One reason for the drama around being ‘politically correct’ is that people who subscribe to this particular belief play video games to escape reality, and they have a strong conception of what reality is like. So, when they see something in a game that belongs only in ‘real life’, such as a women’s body that doesn’t meet certain standards, they can feel that their safe space has been ‘corrupted’ for the sake of an agenda that they interpret as not ‘including’ them. While such rhetoric is not new, the fact that it was repeated in relation to Abby implies there is still an active demographic of players who have adopted this viewpoint, whether consciously or not.

However, video games are, of course, designed and created in the ‘real world’, not in a vacuum. The very idea that a piece of media could not be political is a privilege to a specific worldview. I might enjoy seeing someone with my body type in a video game, and ideally that would be something simply accepted as normal. But it is not, because my body type is not considered to be conventional in media texts. So, seeing someone like me becomes ‘political’.

Protagonist, deuteragonist, antagonist, or anti-hero?

As a games researcher, I’ve spent time writing and publishing around the player response to The Last Of Us and The Last of Us: Part II — and something that struck me was the wide appeal the recent HBO adaption had, attracting viewers who were fans of the game alongside people who rarely played video games at all. The show expanded a brief mention of a gay relationship in the game to a full episode of television that was highly regarded.

I wonder how viewers will react when Abby is revealed in the TV series, or when she kills Joel. It has been faithful to the game so far, and the creators have tended to choose actors who resemble their in-game characters. Viewers who have played the games will not be surprised, or should not be if an appropriately built actor is chosen to play Abby. Of course, that doesn’t mean that there won’t be backlash or outrage.

Over the past decade, and still now, the game industry has been going through a period of change. While more diverse representations are visible, and we have seen much progress, the recent backlash against Abby illustrates that there is still some way to go. With more exposure to challenging characters, my hope is that players will become more open to difference.