Our world has long been one where first-world dictators clog news feeds, and the vision of civil unrest consistently comes through our televisions and timelines. So it’s only natural that our reality begins to be reflected through our screen art, too. For those in the Western world, we’re seemingly still in the midst of trying to get a grip on this ever-evolving homunculus of rising neo-fascist sentiment. It can’t simply be identified by symbols and uniforms anymore and in some instances, we’re still trying to convince people that the problem exists at all.

To create art that portrays and addresses this complex beast properly is no small task. But to do so in games – a medium where the audience expects to engage and scrutinise the work for multiple hours – seems daunting to say the least.

Umurangi Generation works around the idea that fascism is malleable and can coagulate around any one of a number of different traits – disdain for women, the obsession with a plot to create a threat, or religious extremism to name a few.

For Naphtali Faulkner, an Australian-based Ngāi Te Rangi designer, it’s the challenge of identifying this neo-fascist omnipresence that inspired his 2020 game, Umurangi Generation and its additional chapters entitled Macro. The game works around the idea that fascist tendencies can coagulate around any one of a number of different traits – disdain for women, the obsession with a plot to create a threat, or religious extremism to name a few. Faulkner expands: ‘What I wanted to do with [Umurangi Generation] was to explore those very specific ideas of what makes a fascist population.’

Thematically, Umurangi’s inspirations spur from the 2020 Australian bushfires and the governmental mismanagement of it, the apathy from those affected, and the trend of talking around the root of the problem–climate change. As development continued, events such as the impact of COVID-19 and the murder of George Floyd added fuel. Faulkner’s inherent Māori experience also provided a relevant framework: ‘You’ve got an invasive force coming into your home that is everywhere, and you can’t look in a single direction without seeing it. Not just that, but it’s the idea that the problems it creates, it can’t really address. For example, if there’s a problem with capitalism, it’s not like capitalism is going to be able to fix that, because it can’t see what it’s doing wrong,’ he said.

Faulkner explains: ‘What I wanted to do with [Umurangi Generation] was to explore those very specific ideas of what makes a fascist population.’

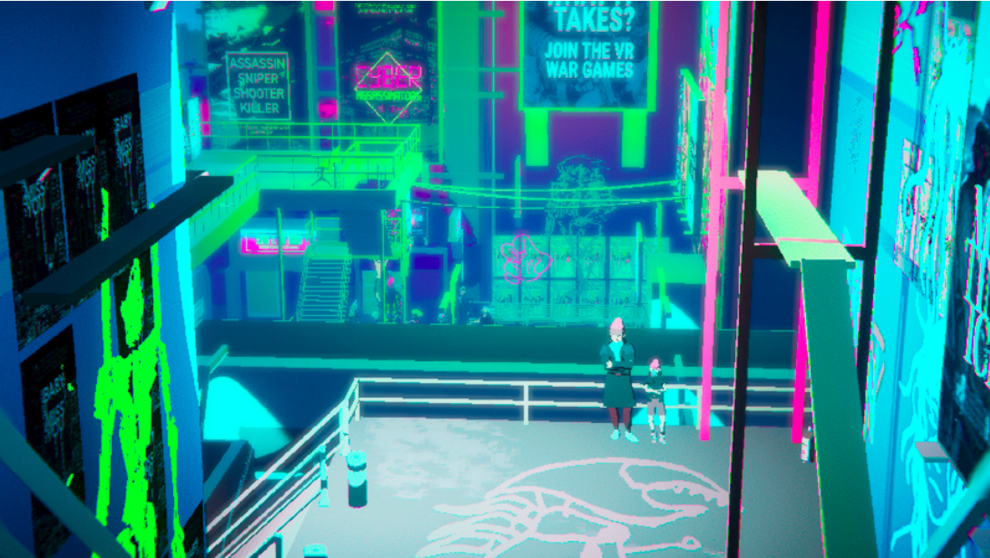

At first blush, the game is about learning how to operate an SLR camera. The player explores a series of still-life scenes set in a near-future Tauranga Aotearoa, finding photo opportunities. At the same time, it’s a game whose mechanics encourage the player to look with intent and a discerning eye, identifying clues in the environment that hopefully spark revelations about the greater context of the world. It’s an aptitude Umurangi hopes the player retains in everyday life.

Image from Umurangi Generation.

The game features no dialogue, its characters mostly remain in still poses, and nothing is spelled out. But the clues that speak to Umurangi’s narrative, its political situation, and its messages about fascism and anti-fascism can all be seen from the get-go if you look hard enough. ‘It’s about positioning people in a space where they get to piece it together for themselves, he said. ‘That way, they walk away with something that they’re really confident in talking about, and they understand how it all interrelates.’

Read: POC game developers celebrate identity with #IamPOCinPlay

To be sure though, the game’s finale beats you over the head with a clear message, literally, by way of a riot officer beating you as an anti-fascist protest is dispersed with force.

The independently-developed Umurangi isn’t the only 2020 game to explicitly deal with the current state of fascism, and it is far from the most high-profile one. Watch Dogs: Legion, the third entry in the blockbuster action franchise from French company Ubisoft, transforms a near-future London into a police state, with private military companies and intelligence agencies seizing control over the city. The player joins resistance movement Dedsec, who work to dismantle the regime by convincing and recruiting everyday citizens to their anti-fascist cause.

As a mainstream game marketed and designed with broad appeal in mind, Watch Dogs: Legion makes a couple of ambitious moves. The main drawcard is the first-of-a-kind feature which allows players to recruit any in-game character to be part of their team of protagonists. The mechanic is notably intertwined with the game’s themes of collective action. The fact that Legion doesn’t shy away from attempts to address the real-world political climate of today also, surprisingly, flies in the face of Ubisoft’s recent history of insisting that their very political games have not been political.

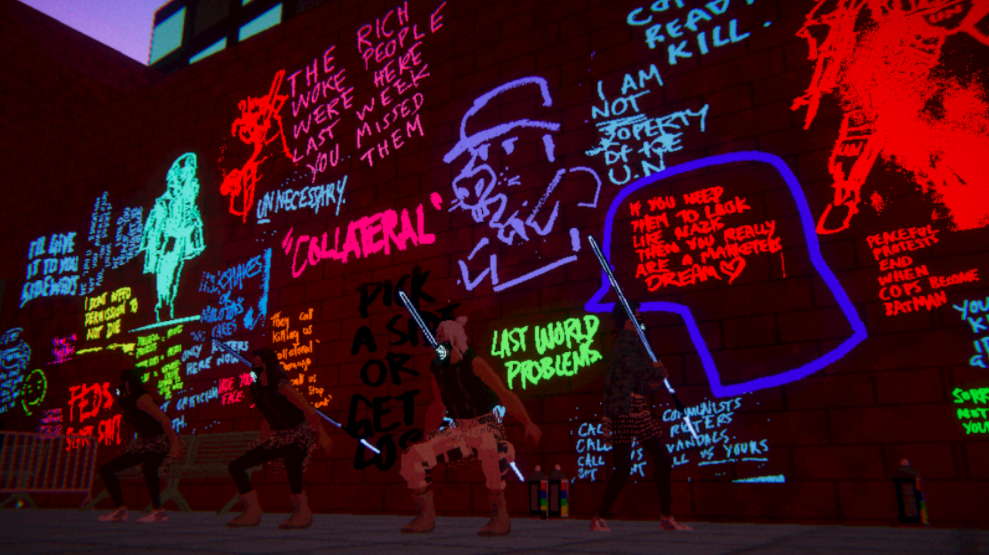

Watch Dogs: Legion. Image via Ubisoft.

Clint Hocking, creative director, said: ‘The most important message of Watch Dogs: Legion is that we can put aside our differences to come together, and we can learn to empathise with people who might seem different from us. The problems we are facing in the world are not going to be solved by lone heroes. Reclaiming our future requires collective action from diverse groups of people with different backgrounds and experiences.’

Despite good intentions and broadly positive messages, Legion has received a share of criticism stemming from its sheer ambitions and template for mass-market appeal, diluting the lessons it has to impart. For one, Legion is a game that revolves around espionage and combat action, meaning that while the scenario might reflect real-world events in some instances, the solutions it posits are fantastical.

Elsewhere, while the diversity of characters you can embody has been praised, it follows reports revealing a swath of sexual misconduct scandals at Ubisoft. Legion’s message of collective action over individual heroism is well-intentioned, but there are few opportunities for your team of activists to actually come together and combine their efforts to exhibit just that.

It’s admirable that Legion brings these ideas to the forefront of a general audience at all; for an everyday consumer to see a version of their current world extrapolated into a worst-case scenario–that might just be the spark they need to consider everything that’s happening.

But with Umurangi Generation, Faulkner didn’t want to pull any punches: ‘For a while, I was thinking whether I should go completely in this direction, because for some people it might be too controversial, too political. And then I started to realise it’s not that people don’t like politics in games. They don’t like left-wing stuff.’ Faulkner cited several games that could easily be identified as right-wing libertarian perspectives on the world, and continued on his path out of continued respect for the audience.

‘Something I kept saying to myself when making [Umurangi Generation] is that fascism is not politically correct. Do not portray fascism as this watered-down thing. Show it as it actually exists.’

Like any other medium, for creators working at profit-driven and relatively risk-averse companies, realising a radical creative vision and ensuring the experience around it is supportive will likely continue to come with compromises. The strides made by one team will hopefully open up the path for another to push the boundaries further. It’s easier for independent creators like Faulkner to react more swiftly to the world around them and create work that can say something with gusto. But if Umurangi Generation and Watch Dogs: Legion have taught us anything, it’s that you can’t enact change alone. It takes a crowd of people and their voices for the message to be heard and sustained. Hopefully, they are just the first of many to come.

(This article has been retimed since its original publication in November 2020.)