It’s been thrilling to witness push-back against Activision Blizzard’s tone-deaf tools designed for the purpose of mimicking diversity. The most important takeaway from this outpouring of critique has been the call to replace these ineffective tools by including diverse individuals behind the scenes. Rather than developing a fancy device to help make cardboard cutout characters, companies should simply hire people with diverse identities to get it done properly.

Hire them, actually listen to them, and allow them to reach positions within companies where they can enact meaningful change. It’s the right conclusion to draw from this whole mess, and for most people, it’s obvious that diverse creator teams make the best, most diverse games.

That said, it’s important to ask why diverse creators should be brought on to replace these ineffective tools, other than the obvious fact that people of varied identities and backgrounds deserve the opportunity to tell their own stories.

My conclusion is that it comes down to an understanding of context and depth, something that can’t be mimicked by a black-and-white tool like the one so proudly touted by Activision Blizzard as a leap forward for inclusion in gaming.

Intersectionality

It begins with intersectionality, a framework with which to view people, whereby you consider how the factors of their identity (sexuality, gender, race, etc) interact with one another, rather than existing as discrete parts. Essentially, it prompts you to consider how one aspect of a person’s identity will be influenced by other aspects, letting you develop a more accurate understanding of the context in which they live.

For an example of intersectionality at work, let’s use myself – a white, transgender individual.

Being transgender, I experience a degree of marginalisation (lack of representation in media, societal disadvantages, potential discrimination in my day-to-day life, etc.) that is a common experience among transgender people. Being white, I experience a degree of privilege (frequent representation in media, systemic racism that favours me, etc.) that is similarly common among white people.

The discrimination I might experience for being transgender is tempered by the systemic privilege of my race – I might be given strange looks at the airport when I go through a scanner, for example, but I’m very unlikely to be chosen for a ‘random’ security check. Because I’m white, I’m unlikely to experience the same degree of discrimination that a transgender person of colour would.

There’s a reason that transphobic hate-crimes disproportionately target people of colour, after all – it’s easier to get away with being transphobic when your victim is also discriminated against in the legal system. Unfortunately, the nature of marginalisation and discrimination is often multiplicative. The more your identity differs from a societal ‘norm’ (in this case, the collection of identity factors that are afforded the most systemic privilege), the exponentially greater your chance of facing discrimination, and at higher severity.

This is a grim truth to consider, I’ll admit. But when you’re creating a character, be it for a video game or otherwise, it isn’t enough to just identify that they’re ‘diverse’ in a set number of ways. You have to be able to understand how a combination of diverse identity factors will interact with one another to establish a believable context.

Why the Activision Blizzard approach to diversity fails

A tool might determine how different somebody is from its baseline ‘norm’, but knowing how different somebody is doesn’t actually tell you much about that person. To achieve that necessary believable context, you’ve got to pursue an intersectional understanding of the identity factors you’re representing. And to do that, you’re either going to have to do extensive research and consult with members of that community, or support a diverse development team who understand those factors with lived experience. Otherwise you’re going to end up with tokenism, and that’s worse than nothing.

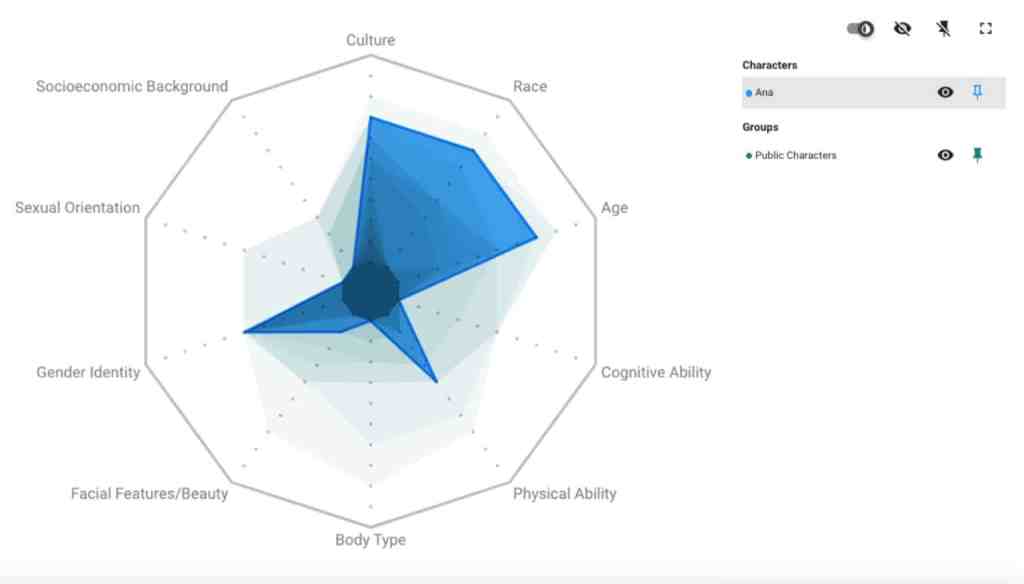

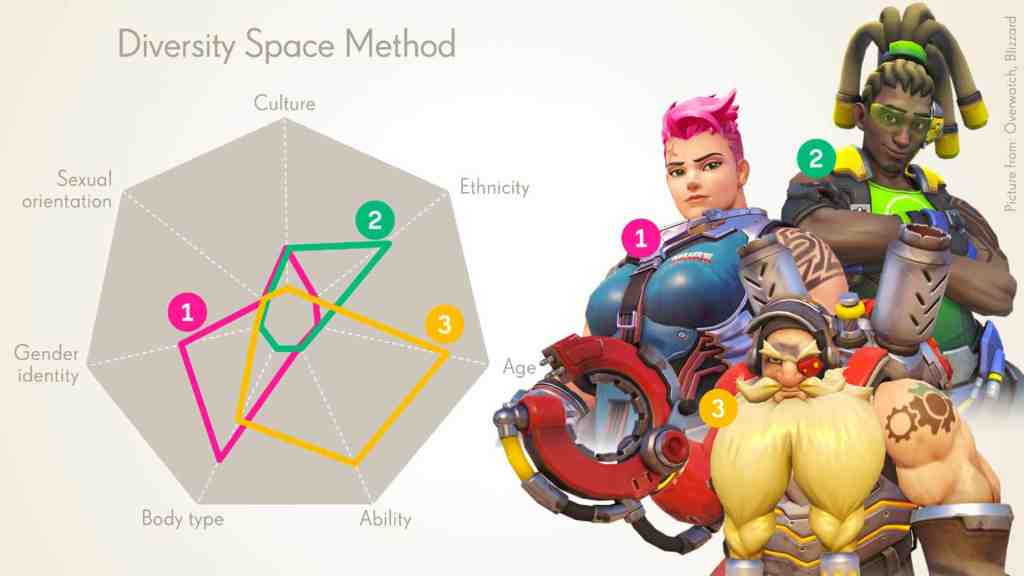

Let’s dig deeper on the character examples given in Activision Blizzard’s Diversity Space Tool – Zarya, Lúcio and Torbjörn. It’s pretty clear from first glance that the tool places more emphasis on characters displaying multiple identity factors differing from the ‘norm’, rather than exploring individual factors and how they interact in depth.

As Torbjörn ranks highly on the ‘Age’, ‘Ability’ and ‘Body Type’ categories, he appears to be significantly more diverse than Lúcio, who is presented as only middling on ‘Culture’, and slightly higher on ‘Ethnicity’.

This is an interesting – and by that, I mean flawed – take on diversity, since I don’t think anyone could legitimately argue that Torbjörn is more-needed representation than Lúcio.

A well-respected, older, married white man who works as an engineer and violently opposes the civil rights movement of a sentient species he helped create vs. a young Brazilian musician who pioneers social change and revolution against a tyrannical corporation attempting to gentrify his home – which do you think is a more important break-away from the norm?

Similarly, Zarya’s presence as a female bodybuilder-turned-soldier is, I would argue, a significantly more diverse character representation than Torbjörn. By exploring a few identity traits in depth, you find characters far more vital to achieving diverse representation than by just ticking as many boxes as possible in the one character.

Digging deep and understanding context is the key to genuine, believable and non-perfunctory representation. It takes an intersectional view, one that understands the many factors that tie together to form a person’s identity, and how those factors affect one another.

This is why we need diverse creators to make better and more diverse games, rather than rely on things like the Diversity Space Tool. If a tool can’t understand the context in which a diverse character exists, and if it places emphasis on quantity rather than quality, then it serves little purpose beyond seeing if you’ve ticked off your ‘diversity quota’ by having a character with a high score in Ethnicity or Sexual Orientation.

Frankly, that sounds tokenistic to me.

Explore Our Trusted Gambling Resources

Discover essential guides to casino sites, betting platforms, and crypto casinos—updated for 2026.