DragonBear Studios is quickly developing a reputation for its thorough approach to inclusivity and cultural sensitivity on a creative and structural level. When we spoke to director Paulina Samy last year, she spoke about the importance of centring Indigenous designers, artists, and stories in the studio’s upcoming debut game, Innchanted. Set in a fantasy Australia informed by Indigenous culture, and developed from first principles through ongoing community consultation, the couch co-op has drawn attention for its thoughtful approach to Indigenous-led design, a process that has been led by Yarrer Gunditj game designer Phoebe Watson.

During GCAP Conference, audiences saw another side of the studio’s multifaceted approach to inclusive game design, with a talk from composer Meena Shamaly, who laid out his composition process of collaborating with First Nations musicians to create a culturally respectful, celebratory, and entertaining score to Innchanted.

Read More: Innchanted, Australian identity, and First Nations culture in videogames

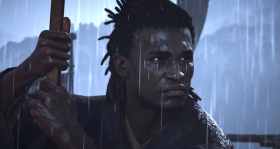

The most recent trailer for Innchanted.

Shamaly has composed soundtracks for film and games, he presents ABC Classic’s Game Show, where he analyses the music of video games. His own musical practice, and experiences as a session musician whose creative and cultural expertise is in Middle Eastern music, informed how he approached musicians who similarly engage with their culture through their music.

Shamaly’s talk ranges from cultural to practical considerations in developing the score as a culturally sensitive, fundamentally collaborative process. In developing this score, he worked with Allara Briggs Pattison, a Yorta Yorta musician who performs as ALLARA, DRMNGNOW’s Kiernan Ironfield, and violinist Eric Avery. The result-in-progress is a score that blends Shamaly playing various guitar-based instruments from around the world and percussion, with these musicians’ Indigenous instruments, techniques, and performance.

Collaboration and connection

Shamaly cited several composers who created dynamic scores that drew on influences outside of their own cultural experience, particularly composer Ludwig Göransson, the white, Swedish composer who won an Academy Award for his original soundtrack to Black Panther. Göransson travelled and consulted extensively across the African continent in preparation for composing the soundtrack, in order to meet collaborators like Senegalese musician Baaba Maal, who contributed instrumentation and an original song to the soundtrack, and Amadou Ba, whose Fula flute performance is the basis of Killmonger’s theme.

‘It’s really important I think that we can identify, and and celebrate that identity within our music, and to be really careful of honouring our cultural integrity, in every way that we create and perform.’

Allara Briggs Pattison

Shamaly took a similar approach to co-developing Innchanted’s soundtrack with Indigenous musicians. He listened to a broad range of Indigenous musicians across a variety of genres; and found that the electric common thread between artists as distinct as Mojo Juju and Baker Boy was ‘the way Indigenous musicians are rooted firmly in culture and yet their art is never static. It is forever, pushing boundaries and mixing influences, but it is so firmly grounded, their heritage.’

To preserve this dynamic quality, Shamaly is creating Innchanted’s score through a series of jam sessions with Indigenous musicians, rather than just writing a score inspired by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander musicians. In his words: ‘It wasn’t about trying to recreate the sound of Indigenous culture, but rather let First Nation musicians express themselves, to shine a light on them and collaborate with them. It’s a conversation.’

Honouring cultural integrity

The first musician Shamaly collaborated with on the Innchanted project was Briggs Pattison, who uses double bass and looping pedals to create ‘grooving, floating’ melodies that are rich with aural texture created with breathwork, vocals, and clapsticks. She views her music as inherently political, as a continuation of a living history of Indigenous song and dance that stretches back to time immemorial: ‘It’s really important I think that we can identify, and and celebrate that identity within our music, and to be really careful of honouring our cultural integrity, in every way that we create and perform.’

‘I would never tell [these musicians] what sounds to make, or what notes to play,’ Shamaly said, ‘It’s more a question of what does your gut tell you, as someone with your own musical practice, and your own connection to the Indigenous culture being depicted in this game.’

ALLARA performs Rekindled Systems.

To sustain this cultural integrity, Briggs Pattison and Shamaly’s creative collaboration began with conversations about each other’s musical practices, and their connection to their heritage. After which, they had a jam session at Shamaly’s studio, where Briggs Pattison had a chance to play the game, and discuss its narrative, and to explore the musical responses that the game prompted in her. This is a method of collaboration Shamaly has followed with all his collaborators, in developing a score that reflected the game, but that also expressed the musicians’ connection to their own culture and language.

During these sessions, the process was entirely instinctive and unguided: ‘I would never tell [these Indigenous musicians] what sounds to make, or what notes to play,’ Shamaly said, ‘It’s more a question of what does your gut tell you, as someone with your own musical practice, and your own connection to the Indigenous culture being depicted in this game.’

Based on these sessions, Shamaly built a library of recordings, which he cut up and edited, as part of a broader dynamic OST. Some of these changes were significant, in order to mesh individual performances into a cohesive videogame score. He uses the example of a yidaki performance by Ironfield, on which he made ‘liberal use’ of effects, until only the original rhythm was recognisable as part of a cohesive piece of music with varied instrumentation; the final result doesn’t produce a better sound on its own, but it fits easily into a soundtrack with other instrumentation.

Shamaly stays in continuous communication with each of the musicians throughout the production process, to ensure his production and composition aren’t overwriting their work: ‘I want to make sure that they feel respected in the process, and that they feel their work is being honoured in this process.’

After using these sounds to develop a more cohesive vision for the soundtrack, he invited the musicians back in to perform written parts based on their earlier performances, putting emphasis on their interpretation of these parts: ‘they can also take these lines that I have written and have their own creative freedom with them. They can even create completely new performances that can then inspire other parts of the soundtrack.

‘This process is forever cyclical and beautiful; it’s just such a positive feedback loop in and of itself.’