Every creative industry in Australia is reeling from the impacts of the COVID pandemic. After two months of cancelled conferences, working remotely, and social distancing measures limiting physical sales of games, how is the small Australian industry, already geographically isolated from the international market, bearing up?

First, The Good News

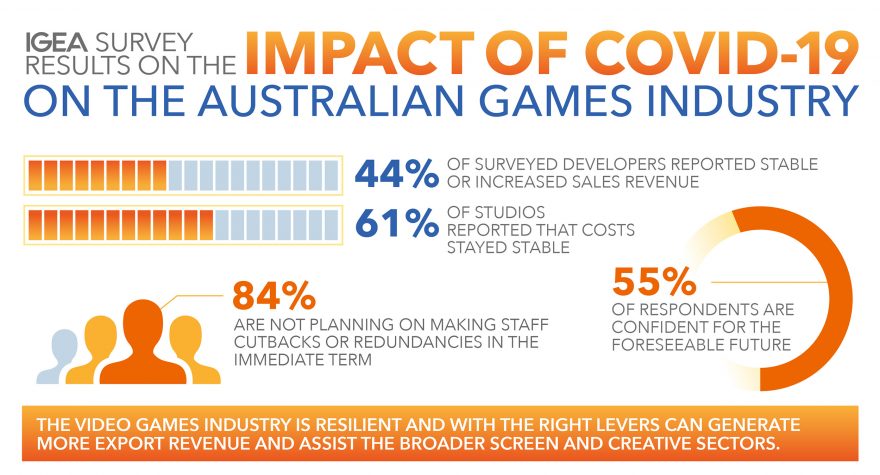

The peak industry association Interactive Games & Entertainment Association (IGEA) have released the results of their survey into the impacts of COVID-19 on the local industry, and they stand in stark relief to the results from other creative sectors: they’re surprisingly positive. 84% of respondents reported that they are not planning to make any staff cutbacks or redundancies, and just over half reported that they had confidence in their studio’s future. At least in the short term, these statistics indicate that things are looking okay:

For established studios, the news seems, tentatively, good. But an industry is more than just its established studios – and Australia’s tiny, remote industry relies on international opportunities for access to new markets.

As Australian games industry researcher Brendan Keogh puts it, game development mostly entails ‘sitting in front of a computer in a room.’

In some very straightforward ways, this kind of labour translates more effectively than a film set, visual arts studio, theatre production, or gig, to remote participation. Keogh notes that remote work and small teams are par for the course in independent games development: ‘Especially in Australia, many developers already work alone, or in small teams with minimal resources. A lot of people already work from home, or in remote teams. Even for teams who share an office, project management tools like Slack and Trello are totally standard, which isn’t always the case for other creative industries.’

Similarly, despite barriers to work, sales from games seem to be doing well internationally, and Australian game developers have reported that boost in income too. As the world plays in, the player bases for co-operative games and digital board games grow.

Keogh also speculates that as disposable entertainment income is funnelled towards popular games titles, indies will feel the knock-on effect of those sales: ‘SMG studio, the developers responsible for critically lauded co-operative game Moving Out last month, tweeted about the studio’s pandemic sales bubble today:

It looks like the impact from Coronavirus on gaming (at least for us) is falling back to “normal”.

I’ve spoken to other devs and they have similar results.

It’s still higher but not as dramatic as in April.

This is revenue by day for mobile. The spikes are weekends pic.twitter.com/hqoe8M349p— SMG: Moving Out! Out now! 📦 (@smgstudio) May 21, 2020

Even as sales have boomed, however, there are games workers outside of big studios who aren’t faring as well. Unsurprisingly, younger and less established game devs and contractors are the hardest hit.

a real blow to contractors

Like all of the creative sector, game development in Australia relies heavily on contractors, whose skills are acquitted on a range of projects via short contracts — but without the face-to-face connection of community events, in-person game jams, meetups, and conferences are put on hold, it will be much harder to break in.

‘If you don’t have the activities of a scene, or local community, with monthly meetups and whatnot, it can be a lot harder to find this kind of work. this will disproportionately impact the more junior worker in the industry,’

Brendan Keogh

Read: How ‘Moving Out’ entertains us as the world stays in

As studios take care to protect their own, making new professional connections for contractors will be harder than ever. This will particularly affect current games students, who are still acquainting themselves with the local industry. Keogh feels that the availability of games industry events, regardless of content or purpose, are educational to emerging game developers: ‘For students in particular, it’s so important for building those networks, make contacts – even just as an opportunity to see what an industry or community even looks like.’

This year, game design students across the country will also forgo in-person exhibitions of their games projects. End of semester and end of year events are valuable opportunities to get acquainted with local developers, and to showcase their skills. Even more valuable are the communication skills that facilitate these in-person connections. The second half of the year draws nearer, and many higher and vocal education facilities are keeping classes online for safety reasons. There are some skills and experiences that, even for games, don’t translate easily to digital spaces.

EDUCATION

Students in shorter courses, or in their final years, will miss out on vital experience exhibiting their work, and learning how to present games on a show floor. These skills are vital for emerging game developers, who hope to work in an industry where showing at events like PAX, E3, and Gamescom, conferences like GDC, GCAP, and festivals like Now Play This, AMAZEfest, and Freeplay Independent Games Festival, can help connect them to potential publishers, and funders.

‘Without the context, few people bother downloading and playing student games – and if they do, the experience is still so different.’

Brendan Keogh

Platforms like Itch, and the reach of social media, make up for some of this, as students can self-publish small projects with relative ease. Keogh notes that even if they publish or present online, students will have a much less receptive audience for their work, outside of the collegiate atmosphere of an exhibition: ‘Without the context, few people bother downloading and playing student games – and if they do, the experience is still so different.’

Australian developers rely heavily on professional connections forged over a precious few days at international conventions and conferences. That means that strong exhibiting and communication skills are vital. Keogh points out that universities are developing alternatives – he mentions that SAE Brisbane replaced their end of trimester exhibition with a series of student presentations via Zoom – but for now, no perfect digital analogue exists.

Looking forward

While 84% of studios are planning to hold onto all their staff at this point, the destabilising and isolating elements of the pandemic will likely hit freelancers hard. Work that would once have been contracted out may be more likely stay in-house, and as networking opportunities dry up, the contracts that do exist will go to people with existing connections.

In an industry that relies heavily on short contracts, this development could change the face of Australian games dramatically as it becomes harder and harder for students and marginalised people to find a seat at the table. Ultimately, it’s impossible to forecast until we’re all back in the offices, classrooms, galleries, show floors, bars, arcades, and living rooms where games were being made before the pandemic hit.